David Mitchell

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

© 2010

For K, H & N with love

Author’s Note

The port of Batavia on the island of Java was the headquarters of the Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally ‘United East Indian Company’) and the point of embarkation and return for VOC ships sailing the Nagasaki run. During the Japanese occupation of the Indonesian archipelago during World War II, Batavia was renamed Jakarta.

Throughout the novel, the lunar calendar is used to denote Japanese dates. The lunar calendar could be anything from three to seven weeks ‘behind’ the Gregorian calendar, depending on the year. Thus ‘the First Day of the First Month’ corresponds not to 1st January but to a varying date between the back end of January and the rear middle of February. Years are referred to by their Japanese era names.

Throughout the text, Japanese names are ordered with the family name first.

PART I The Bride for Whom We Dance

I The House of Kawasemi the Concubine, above Nagasaki

The Ninth Night of the Fifth Month

‘Miss Kawasemi?’ Orito kneels on a stale and sticky futon. ‘Can you hear me?’

In the rice paddy beyond the garden, a cacophony of frogs detonates.

Orito dabs the concubine’s sweat-drenched face with a damp cloth.

‘She’s barely spoken,’ the maid holds the lamp, ‘for hours and hours…’

‘Miss Kawasemi, my name’s Aibagawa. I’m a midwife. I want to help.’

Kawasemi’s eyes flicker open. She manages a frail sigh. Her eyes shut.

She is too exhausted, Orito thinks, even to fear dying tonight.

Dr Maeno whispers through the muslin curtain. ‘I wanted to examine the child’s presentation myself, but…’ the elderly scholar chooses his words with care ‘… but this is prohibited, it seems.’

‘My orders are clear,’ states the chamberlain. ‘No man may touch her.’

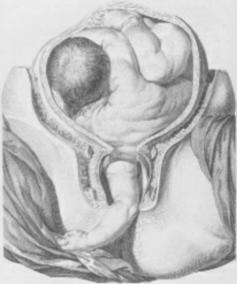

Orito lifts the bloodied sheet and finds, as warned, the foetus’s limp arm protruding from Kawasemi’s vagina up to the shoulder.

‘Have you ever seen such a presentation?’ asks Dr Maeno.

‘Yes: in an engraving, from the Dutch text Father was translating.’

‘This is what I prayed to hear! The Observations of William Smellie?’

‘Yes: Dr Smellie terms it,’ Orito uses the Dutch, ‘ “Prolapse of the Arm”.’

Orito clasps the foetus’s mucus-smeared wrist to search for a pulse.

Maeno now asks her in Dutch, ‘What are your opinions?’

There is no pulse. ‘The baby is dead,’ Orito answers, in the same language, ‘and the mother will die soon, if the child is not delivered.’ She places her fingertips on Kawasemi’s distended belly and probes the bulge around the inverted navel. ‘It was a boy.’ She kneels between Kawasemi’s parted legs, noting the narrow pelvis, and sniffs the bulging labia: she detects the malty mixture of grumous blood and excrement, but not the stench of a rotted foetus. ‘He died one or two hours ago.’

Orito asks the maid, ‘When did the waters break?’

The maid is still mute with astonishment at hearing a foreign language.

‘Yesterday morning, during the Hour of the Dragon,’ says the stony-voiced housekeeper. ‘Our lady entered labour soon after.’

‘And when was the last time that the baby kicked?’

‘The last kick would have been around noon today.’

‘Dr Maeno, would you agree the infant is in’ – she uses the Dutch term – ‘the “transverse breech position”?’

‘Maybe,’ the doctor answers in their code-tongue, ‘but without an examination…’

‘The baby is twenty days late, or more. It should have been turned.’

‘Baby’s resting,’ the maid assures her mistress. ‘Isn’t that so, Dr Maeno?’

‘What you say…’ the honest doctor wavers ‘… may well be true.’

‘My father told me,’ Orito says, ‘Dr Uragami was overseeing the birth.’

‘So he was,’ grunts Maeno, ‘from the comfort of his consulting rooms. After the baby stopped kicking Uragami ascertained that, for geomantic reasons discernible to men of his genius, the child’s spirit is reluctant to be born. The birth henceforth depends on the mother’s will-power.’ The rogue, Maeno needs not add, dares not bruise his reputation by presiding over the still-birth of such an estimable man’s child. ‘Chamberlain Tomine then persuaded the Magistrate to summon me. When I saw the arm, I recalled your doctor of Scotland, and requested your help.’

‘My father and I are both deeply honoured by your trust,’ says Orito…

… and I curse Uragami, she thinks, for his lethal unwillingness to lose face.

Abruptly, the frogs stop croaking and, as though a curtain of noise falls away, the sound of Nagasaki can be heard, celebrating the safe arrival of the Dutch ship.

‘If the child is dead,’ says Maeno in Dutch, ‘we must remove it now.’

‘I agree.’ Orito asks the housekeeper for warm water and strips of linen, and uncorks a bottle of Leiden salts under the concubine’s nose to win her a few moments’ lucidity. ‘Miss Kawasemi, we are going to deliver your child in the next few minutes. First, may I feel inside you?’

The concubine is seized by the next contraction, and loses her ability to answer.

Warm water is delivered in two copper pans as the agony subsides. ‘We should confess,’ Dr Maeno proposes to Orito in Dutch, ‘the baby is dead. Then amputate the arm to deliver the body.’

‘First, I wish to insert my hand to learn whether the body is in a convex lie or concave lie.’

‘If you can discover this without cutting the arm’ – Maeno means ‘amputate’ – ‘do so.’

Orito lubricates her right hand with rape-seed oil and addresses the maid: ‘Fold one linen strip into a thick pad… yes, like so. Be ready to wedge it between your mistress’s teeth, otherwise she might bite off her tongue. Leave spaces at the sides, so she can breathe. Dr Maeno, my inspection is beginning.’

‘You are my eyes and ears, Miss Aibagawa,’ says the doctor.

Orito works her fingers between the foetus’s biceps and its mother’s ruptured labia until half her wrist is inside Kawasemi’s vagina. The concubine shivers and groans. ‘Sorry,’ says Orito, ‘sorry…’ Her fingers slide between warm membranes and skin and muscle still wet with amniotic fluid and the midwife pictures an engraving from that enlightened and barbaric realm, Europe…

If the transverse lie is convex, recalls Orito, where the foetus’s spine is arched backwards so acutely that its head appears between its shins like a Chinese acrobat, she must amputate the foetus’s arm, dismember its corpse with toothed forceps, and extract it, piece by grisly piece. Dr Smellie warns that any remnant left in the womb will fester and may kill the mother. If the transverse lie is concave, however, Orito has read, where the foetus’s knees are pressed against its chest, she may saw off the arm, rotate the foetus, insert crotchets into the eye-sockets, and extract the whole body, head first. The midwife’s index finger locates the child’s knobbly spine, traces its midriff between its lowest rib and its pelvic bone, and encounters a minute ear; a nostril; a mouth; the umbilical cord; and a prawn-sized penis. ‘Breech is concave,’ Orito reports to Dr Maeno, ‘but cord is around neck.’