It was mumbo jumbo. Heard but not read, and heard only once, the words vanishing into silence before he could seize their meaning, Henry retained hardly anything and understood even less. He didn't know how to react, so he said nothing. But the taxidermist wasn't saying anything either.

"I didn't get the last one," Henry said, at length.

"Aukitz, a-u-k-i-t-z."

"It sounds like German, but I don't recognize the word."

"No, it's not. It's a kind of onelongword."

"It doesn't seem that long to me, only six letters."

"No, that's not it."

The taxidermist turned the page and pointed with his finger at a word in the middle of it: onelongword.

"What does it mean?"

"It's one of Beatrice's ideas."

He searched and found:

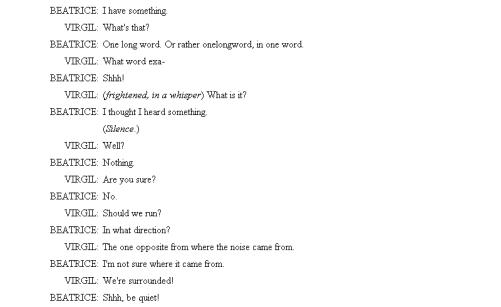

"A scene follows where they think they've been found, but they're wrong. They're still safe. They come back to onelongword."

"Say that one again," Henry said.

The taxidermist nodded, acknowledging that Beatrice and Henry had the same opinion of Virgil's onelongword.

"Aukitz is a variation on a onelongword. Beatrice proposes that the word be printed in every book, magazine and newspaper, in a spot conspicuous or discreet, depending on the wishes of the author or publisher, to indicate that the language within is knowing of the Horrors."

"And all the other items in the list, this sewing kit for the Shirt, have the same purpose, to make things knowing?"

"Yes, exactly."

"Can I see the list, please?"

The taxidermist hesitated, but then passed it to Henry.

"Thank you," Henry said, managing to check any outward sign of surprise. He could barely believe it. He was certain the taxidermist would snatch the page back before he had time to read it. Finally he would stop the flow of the taxidermist's words and have them before his eyes, fixed and immobile, like one of his mounted animals. The words were lightly indented into the page, creating a Braille-like embossment on the reverse side, the result of being mechanically typed.

The list was laid out in a column:

A Horrors' Sewing Kit

a howl,

a black cat,

words and occasional silence,

a hand gesture,

shirts with one arm missing,

a prayer,

a set speech at the start of every parliamentary session,

a song,

a food dish,

a float in a parade,

commemorative porcelain shoes for the people,

tennis lessons,

plain truth common nouns,

onelongword,

lists,

empty good cheer expressed in extremis,

witness words,

rituals and pilgrimages,

private and public acts of justice and homage,

a facial expression,

a second hand gesture,

a verbal expression, [sic] dramas,

68 Nowolipki Street,

games for Gustav,

a tattoo,

an object designated for a year,

aukitz.

The full stop after the last item had perforated the page. The list had a curious poetry to it, an anti-poetry of the odd and the oddly juxtaposed, of the familiar and the strange. Henry's eyes stopped for a moment on an item towards the end of the list: 68 Nowolipki Street. The address tugged at his memory, but he couldn't tell why. He moved on. Clearly the taxidermist felt very strongly about this list and Henry was expected to ask questions about it. But he sighed inwardly. To tell a story through a list. It wouldn't be any more killing to an audience if he sat on a stage and started reading from the phone book. Henry arbitrarily picked an item.

"What are 'plain truth common nouns'?" he asked.

"They're judgments that are backed up by the dictionary. It's Beatrice's idea. So: murderers, killers, exterminators, torturers, plunderers, robbers, rapists, defilers, brutes, louts, monsters, fiends-words like that."

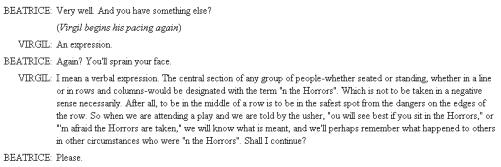

"I get the idea." Henry chose another item from the list. "And this 'verbal expression'?"

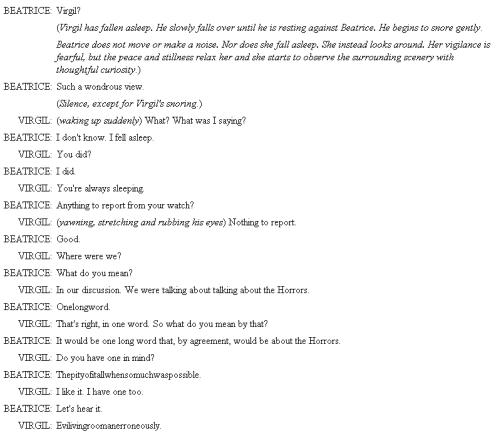

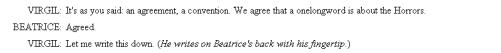

The taxidermist found the scene:

The taxidermist stopped.

Henry nodded. "And '[ sic] dramas'?"

"Sic is the Latin word for thus," the taxidermist replied. "It's used to indicate that a printed word is printed exactly as intended or is correctly copied from the erroneous original."

"Yes, I'm familiar with the use of sic."

"Virgil has this idea for short plays where every word, every single word, would be qualified by sic, because every word, in the light of the Horrors, is now erroneous. There's a Hungarian writer who writes like that, in a way."

The taxidermist didn't search for the scene where Virgil presents his [ sic] dramas, nor did he tell Henry which Hungarian writer he was referring to. Instead, he fell silent. They seemed to be in an intermission, so to speak. Henry decided to seize the opportunity and try again, but this time from a different angle, from the point of view of character development rather than plot and action. That might help the taxidermist with his play-and get him to talk about its genesis.

"Tell me, how do Beatrice and Virgil change over the course of the play?" Henry asked.

"Change? Why should they change? They have no reason to change. They've done nothing wrong. They're exactly the same at the end of the play as they were at the beginning."

"But they talk. They notice and realize things. They reflect in quiet moments. They gather up the items that go into the sewing kit. All these change them, no?"

"Absolutely not," the taxidermist said firmly. "They're the same. If we had met them the next day, we would have said they were no different from the previous day."

Henry wondered what his creative writing friend would have said at that moment. He had found three good words, more than that, in fact, but no story was coming from them.

"But in a story, the characters-"

"Animals have endured for countless thousands of years. They've been confronted by the most adverse environments imaginable and they've adapted, but in a manner absolutely consistent with their natures."

"That's true in life. I fully agree. I have no doubts about the organic workings of evolution. In a story, however-"

"It is we who have to change, not they." The taxidermist seemed flustered.

"I agree with you. There's no future without an environmental conscience. But in a story-here, take Julian in the Flaubert story you sent me. Over the course-"

"If Virgil and Beatrice have to change according to someone else's standards, they might as well give up and be extinct."

At that moment, it was Henry who gave up. "Yes, I see your point," he said, to placate the taxidermist.

"They do not change. Virgil and Beatrice are the same before, during and after."

Henry looked at the list again.

"Where's this '68 Nowolip-'" he was about to ask, to change the topic, but the taxidermist abruptly raised the palm of his hand in the air.

Henry shut up. The taxidermist got up and came round to his side of the desk. Henry felt a slight measure of apprehension.

"Only one thing really counts," said the taxidermist. It was nearly a whisper.

"What's that?"

The taxidermist slowly pulled the page from Henry's hand. Henry let it slide through his fingers. The taxidermist laid it on the desk.

"This," he said.

He took the lamp in one hand and with the other he ran his fingers against the direction of the fur at the base of Virgil's tail.

"This here," he said.

Henry looked. On the skin now exposed was a stitch, a suture, that circled the base of the tail. It looked purple, medical, horrible.