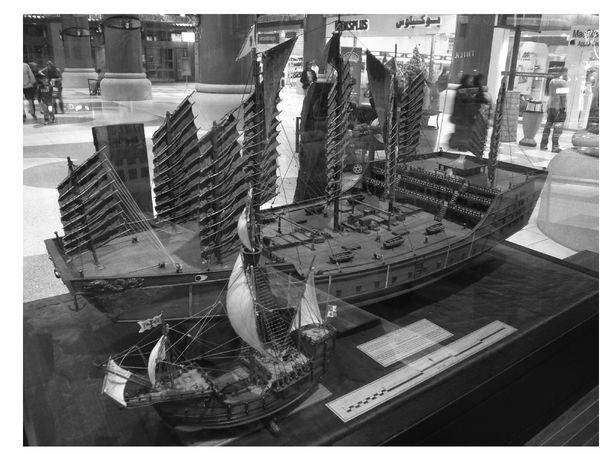

A model of one of Zheng He’s ships, shown in comparison to one of Christopher Columbus’s

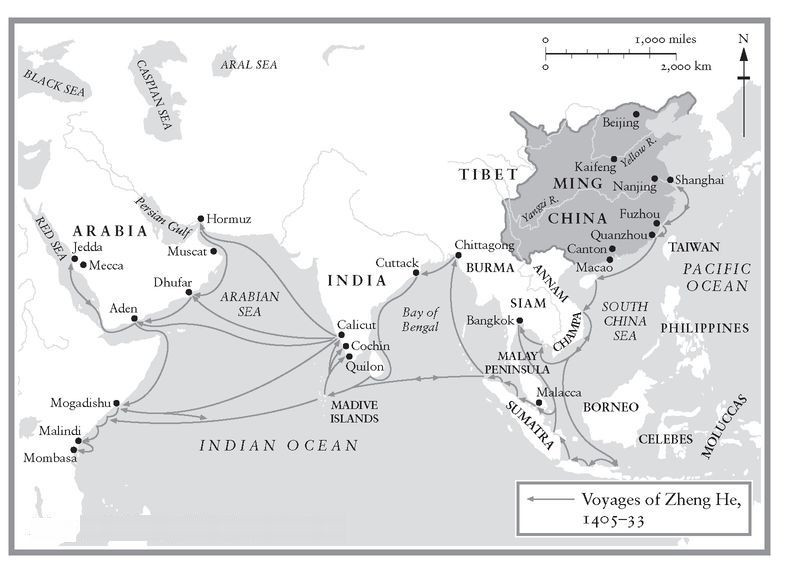

Map 7. Zheng He’s Expeditions

As we saw in Chapter 2, Britain was able to escape the growing resource constraints at the end of the eighteenth century by deploying the resources of its colonies, together with an abundant supply of accessible domestic coal. But what exactly happened to China, which enjoyed neither? There was almost certainly enough capital available, especially given the relatively small amounts involved in the take-off of the cotton industry in Britain. Although Chinese merchants did not enjoy the same kind of independent and privileged status that they did in Britain, always being subordinate to the bureaucracy and the landowning gentry, they were widely respected and enjoyed growing wealth and considerable power. [221] There may have been rather less protection for investment in comparison with Europe, but nonetheless there were plenty of very large Chinese enterprises. China ’s markets were no less sophisticated than those of Europe and were much longer established. Mark Elvin argues that the reason for China ’s failure was what he describes as a ‘high-level equilibrium trap’. [222] China ’s shortage of resources in its densely populated heartlands became increasingly acute: there was a growing lack of wood, fuel, clothing fibres, draught animals and metals, and there was an increasing shortage of good farmland. Hectic deforestation continued throughout the nineteenth century and in some places the scarcity of wood was so serious that families burned little but dung, roots and the husks of corn. In provinces such as Henan and Shandong, where population levels were at their most dense, forest cover fell to between 2 per cent and 6 per cent of the total land area, which was between one-twelfth and one-quarter of the levels in European countries like France at the time. [223] The pressure on land and other resources was driven by the continuing growth of population in a situation of relative technological stasis. Lacking a richly endowed overseas empire, China had no exogenous means by which it could bypass the growing constraints.

With the price of labour falling, profit margins declining and static markets, there was no incentive to invest in labour-saving machinery; instead there was a premium on conserving resources and fixed capital. In such a situation there was little reason to engage in the kind of technological leap into the factory system that marked Britain ’s Industrial Revolution. In other words, it was rational for the Chinese not to invest in labour-saving machinery. As Elvin argues:

In the context of a civilization with a strong sense of economic rationality, with an appreciation of invention such that shrines were erected to historic inventors… and with notable mechanical gifts, it is probably a sufficient explanation of the retardation of technological advance. [224]

With growing markets and a rising cost of labour, on the other hand, investment in labour-saving machinery was entirely rational in the British context and was to unleash a virtuous circle of invention, application, increased labour productivity and economic growth; in contrast, China remained trapped within its old parameters. In Britain the domestic system, based on small-scale family units of production, proved to be the precursor of the factory system. In China, where such rural industrialization was at least as developed as it was in Britain, it did not. While Britain suggested a causal link between the domestic and the factory systems, this was not true in China: widespread rural industrialization did not lead to a Chinese industrial revolution. [225]

THE CHINESESTATE

The most striking difference between Europe and China was not in the timing of their respective industrializations, which in broad historical terms was similar, separated by a mere two centuries, but rather the disparity between the sizes of their polities, which has persisted for at least two millennia and whose effects have been enormous. It is this, above all, which explains why Europe is such a poor template for understanding China. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Europe was never again to be ruled, notwithstanding the ambitions of Napoleon and Hitler, by an imperial regime with the capacity to exercise centralized control over more or less the entire continent. Political authority, instead, was devolved to many small units. Even with the creation of the modern nation-state system, and the unification of Germany and Italy, Europe remained characterized by its division into a multi-state system. In contrast, China retained the imperial state system that emerged after the intense interstate competition — the Warring States period — that ended in the third century BC, though this was to assume over time a range of different forms, including, as in the case of the Mongol Yuan and the Manchu Qing dynasties, various phases of foreign rule. [226] Apart from Outer Mongolia, China’s borders today remain roughly coterminous with those the country acquired during the period of its greatest geographical reach under the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). China ’s equilibrium state has been that of a unified agrarian empire in contrast to Europe, which for two millennia has been an agglomeration of states. [227]

From this follows a fundamental difference in contemporary Chinese and European attitudes: while the Chinese attach greater importance to unity than literally anything else, the Europeans overwhelmingly believe in the nation-state rather than European-wide sovereignty, the European Union notwithstanding. The underlying strength of the Chinese desire for unity is illustrated by the fact that, while the rise of nationalism in Europe in the nineteenth century resulted in the break-up of old empires and the creation of many new states, this has never happened, and shows no sign of happening, in China. The Chinese commitment to unity has three dimensions: the fundamental priority attached to unity by both the state and the people; the central role expected of the state in ensuring that this unity is maintained; and a powerful sense of a common Chinese identity that underpins this overarching popular commitment to unity. This unity could never be taken for granted: China has spent around half its history in varying degrees of division, which, in the light of the country’s size and diversity (far greater than that of Europe), is not surprising. As a result of its attachment to unity, China has largely escaped the intra-state wars that have scarred Europe ’s history over many centuries, though its periods of disunity and fragmentation have often carried a very heavy cost in terms of war and famine, notably from the mid nineteenth to the mid twentieth century, when it was chronically divided. [228] China ’s frequent experience of disunity and its baleful consequences have served to reinforce its commitment to unity, a tradition that began with Confucius — who, living during the Warring States period, was witness to the huge cost of instability and conflict, and preached the importance of harmony.

[223] James Kynge, China Shakes the World: The Rise of a Hungry Nation (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2006), pp. 131-2.

[225] Ibid., pp. 281-2; Bin Wong, China Transformed, pp. 34, 41-4, 49; Mark Elvin, ‘The Historian as Haruspex’, New Left Review, 52, July-August 2008, p. 96.

[228] It can also be argued that if, like Europe, China had been composed of a group of competitive nation-states, this would have made governance rather less forbidding and might also, at times, have stimulated greater innovation; Lucian W. Pye, Asian Power and Politics: The Cultural Dimensions of Authority (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 64.