If Japan was the great exception, the only non-Western country to begin its industrialization in the nineteenth century, China was an example of the opposite: a country which failed to industrialize, even though it enjoyed a similar level of development to Japan in 1800. As a result, China found itself hugely outdistanced by Europe and the United States over the course of the nineteenth century, and also by Japan towards the end of it. After 1800, and especially from the middle of the century, China suffered from growing economic weakness, near implosion, debilitating division, defeat, humiliation and occupation at the hands of foreign powers, and a progressive loss of sovereignty. Disastrous though its fortunes were in the period between 1850 and 1950, however, their consequences should not be overstated. China ’s progress after 1949, and especially since 1978, suggests that the roots of its contemporary dynamism lie in its own history rather than being mainly a consequence of its turn to the West: even if it did not appear so at the time, all was far from lost in the century of humiliation. [191] Nonetheless, this period was to leave deep psychological scars. Like Japan, moreover, China ’s modernization was to take a very different path from that of the West. [192]

A PLACE IN THE SUN

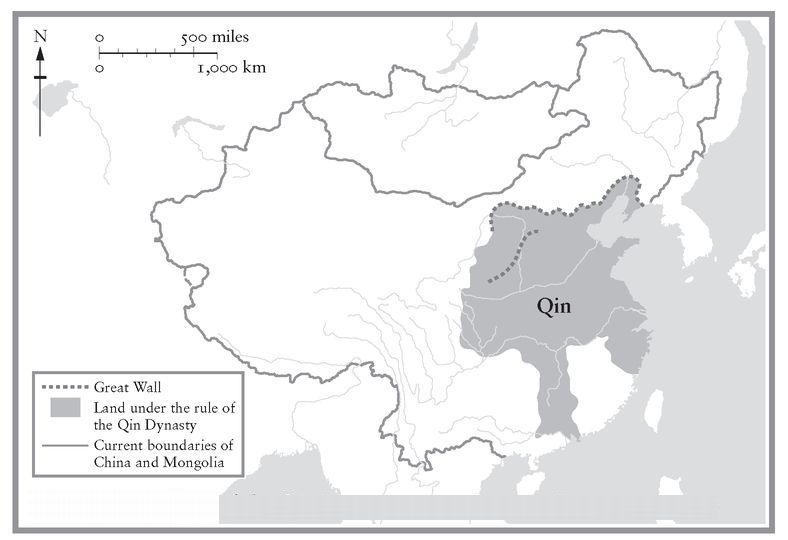

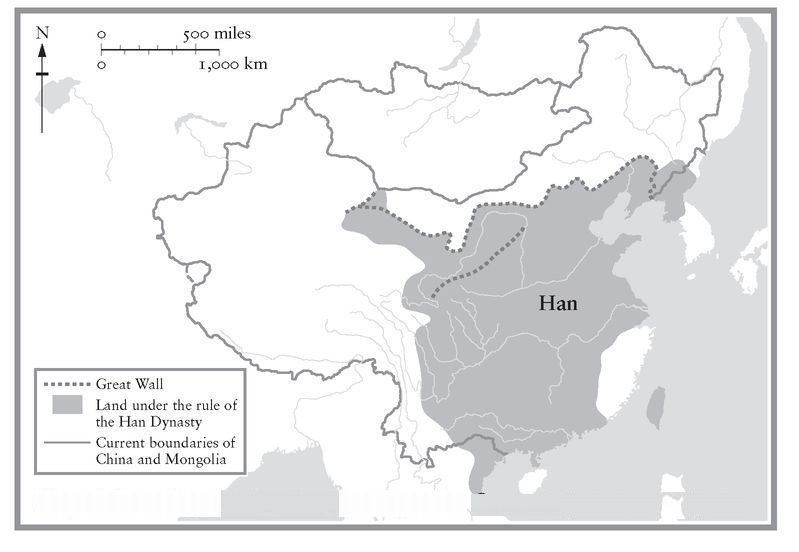

China had already begun to acquire its modern shape in the centuries leading up to the birth of Christ. [193] The victory of the so-called First Emperor (Qin Shihuangdi, the Western name for China being derived from his family name, Qin) marked the end of the Warring States period (475–221 BC) — an endless series of conflicts between the numerous Chinese states of the time which resembled a much later phase of European history — and the beginning of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). By 206 BC the boundaries of the Qin Empire contained much of what we now regard as the heartland of modern China, stretching to Vietnam in the south and as far as the Great Wall in the north, including the densely populated region between the Yangzi and the Yellow rivers (see Map 5). Following the fall of the Qin dynasty, the country continued to expand rapidly during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), achieving its furthest extent in the period 141-87 BC (see Map 6), when the Chinese armies penetrated into southern Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula in the north-east, and south and south-west as far as northern Vietnam. [194] Over the next millennium or so, China continued to expand to the north, north-east, north-west, south and south-east. [195] The huge size that China ultimately acquired was related to the natural borders of its continental land mass, bounded by the steppe in the north, the coastline to the south and east, and the mountainous regions to its south-east. [196]

Extensive internal migration, improving communications and many centuries of unity or near unity helped to foster a relatively homogeneous culture across what was, for its time, a massive population. The Qin dynasty, short though its life may have been, constructed over 4,000 miles of imper-ial highways, as many as the Roman Empire. [197] A centralized state, and a sophisticated statecraft, took root based on the teachings of Confucius (551–479 BC), who was to exercise a huge influence over the Chinese political and moral universe for more than two millennia. Weights, measures and currency were standardized. The distinctive customs that we associate with China — including the mandate of Heaven, a family structure resting on filial piety, a language that used common signs and symbols, and a religion based on ancestral worship — were well established by the time of the Qin dynasty. During the first millennium AD, therefore, China was to acquire — given the fact that in practice it embraced many different peoples — an unusually strong sense of cultural identity. [198] One of the most striking features of Chinese history has been that, although it has been invaded from the north many times — notably by the Mongols in the thirteenth century and the Manchu in the seventeenth — all invaders, bar the Mongols, once secure in power, sought to acquire the customs and values of the Chinese and to rule according to their principles and their institutions: a testament to the prestige enjoyed by the Chinese and the respect accorded to their civilization by their northern adversaries. [199] The persistence and steady spread of the Chinese language is a further indication of the strength of the culture: the constant invasions from the north, by obliging the population to stay mobile, kept the language from becoming atomized into different dialects, at the same time making the Chinese themselves more aware of, and therefore also protective of, both their language and culture. [200] The early emergence of a Chinese identity is, perhaps more than anything else, the key to China as we know it today, for without that, China could not have remained a relatively unified country for over two millennia and would have been shorn of its most striking characteristic: its size.

Map 5. Boundary of the Qin Dynasty at its Greatest Extent, c.206 BC

Map 6. Boundary of the Han Dynasty at its Greatest Extent, 141-87 BC

Historically, relatively advanced forms of agriculture enabled societies to sustain large populations and provided propitious conditions for the development of organized states; China was a classic example of this phenomenon. It is now believed that millet and rice first appeared in northern and southern China respectively 12,000 years ago, earlier even than in Mesopotamia, where sedentary agriculture began about 8,000 years ago. Although North China has long sustained ‘dry’ agriculture by way of cereals, barley and various kinds of millet, it was the wet cultivation of rice, which developed slowly from the beginning of the first millennium and which was in full swing by its end, that was later to give a major boost to Chinese agriculture, resulting in a shift in the economic centre of gravity from the central plain to the lower Yangzi basin. New methods of wet rice cultivation were introduced, including the planting of seedlings, early ripening varieties of rice, the systematic selection of species, new tools such as a chain with paddles which made it possible to lift water from one level to another, and sophisticated forms of irrigation. These made Chinese wet rice farming one of the most advanced agricultural techniques in the world, generating extremely high yields. [201] During the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279), these advanced techniques were generalized across large tracts of the country, pushing south as the frontier was steadily extended. [202] Sustained by agrarian prosperity, the population expanded rapidly, almost doubling between 1000 and 1300. [203] Between AD 500 and 900 bricked roads were built across the middle of the Chinese empire such that the capital (known then as Chang’an, now as Xi’an) was only eight to fourteen days’ travel from any reasonably sized city. Even more significant was the spread of water transport in the form of rivers, canals and coastal shipping. These various waterway systems became part of an integral network that was to form the basis of a nationwide market that steadily took shape by 1200. As Marco Polo, a resident of Venice, Europe ’s greatest seaport, observed of the Yangzi in the late thirteenth century:

[191] Paul A. Cohen, Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), p. 79.

[192] Ibid., pp. 81, 151-2; Huang Ping, ‘“Beijing Consensus”, or “Chinese Experiences”, or What?’, unpublished paper, 2005, pp. 5–8; Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic?: Elite, Class and Regime Transition (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004), p. 85.

[193] Jacques Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization, 2nd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 103-6; Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years (London: Vintage, 1998), pp. 323; also pp. 413-16.

[199] Ibid., pp. 51, 106; Nicholas Ostler, Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (London: HarperCollins, 2005), p. 171; for successive historical examples of this phenomenon, see Lovell, The Great Wall.