Growing numbers of foreign students are taking courses at Chinese universities. During the 2003 academic year, 77,628 foreign students were seeking advanced degrees at Chinese universities, of whom around 80 per cent were from other Asian countries. South Korea accounted for by far the largest number, almost half, but others came from Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Nepal and elsewhere. [1308] In addition, Chinese students study abroad in large numbers, especially in the United States but also in the UK. The number of Chinese studying in the United States has been around 60,000 a year since 2001, while Chinese enrolments in the UK leapt to over 50,000 in 2003-4. [1309]

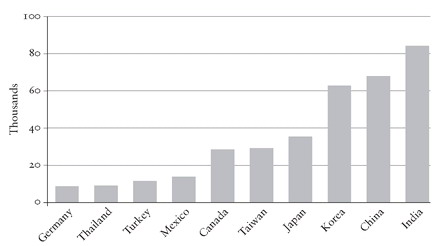

Figure 53. Origin of international students in the United States, 2007.

It seems likely that Chinese universities will, over the next two decades, rise steadily up the global rankings to eventually occupy positions within the top ten. In order to accelerate this process the government is making determined attempts to attract leading overseas Chinese scholars to take up appointments at Chinese universities. [1310] Universities like Beijing, Tsinghua, Fudan and Renmin will, in time, become institutions of recognized global excellence that are increasingly able to attract some of the best scholars from around the world, Chinese or otherwise, while the trend already evident for Chinese universities to become a magnet for students in East Asia will grow as they begin to perform an equivalent academic role in the region to that played by the Chinese economy.

CHINESE CULTURE AS SOFT POWER

When a country is on the rise, a virtuous circle of expanding influence tends to develop. As China grows more powerful, more and more people want to know about it, read about it, watch television programmes about it and go there as tourists. As China grows richer and its people enjoy expanding horizons, so the cultural output of the country will increase exponentially. Poor countries have few resources to devote to art galleries or arts centres; can sustain, at best, only a small film industry and a somewhat prosaic television service; can afford only threadbare facilities for sport; while their newspapers, unable to support a cohort of foreign correspondents, rely instead on Western agencies or syndicated articles for foreign coverage. A report several years ago, for example, showed that only 15 per cent of Chinese men aged between fifteen and thirty-five actively participated in any sporting activity, compared with 50 per cent in the US, while on average the country has less than one square metre of sports facilities per person. [1311] As China grows increasingly wealthy and powerful, it can afford to raise its sights and entertain objectives that were previously unattainable, such as staging the Olympic Games, or producing multinational blockbuster movies, or promoting the Shaolin Monks to tour the world with their kung fu extravaganza, or building a state-of-the-art metro system in Beijing, or commissioning the world’s top architects to design magnificent new buildings. Wealth and economic strength are preconditions for the exercise of soft power and cultural influence.

Hollywood has dominated the global film industry for more than half a century, steadily marginalizing other national cinemas in the process. But now there are two serious rivals on the horizon. As Michael Curtin argues:

Recent changes in trade, industry, politics and media technologies have fuelled the rapid expansion and transformation of media industries in Asia, so that Indian and Chinese centres of film and television production have increasingly emerged as significant competitors of Hollywood in the size and enthusiasm of their audiences, if not yet in gross revenues… Media executives can, for the very first time, begin to contemplate the prospect of a global Chinese audience that includes more moviegoers and more television households than the United States and Europe combined. [1312]

Over the last decade, mainland film directors like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige have joined the Taiwanese Ang Lee in becoming increasingly well known in the West, as have Chinese film stars like Gong Li, Jet Li, Zhang Ziyi and Hong Kong’s Jackie Chan. In recent years there has been a series of big-budget, blockbuster Chinese movies, often made with money from China, Hong Kong and the United States, which have been huge box office successes both in China and the West. Obvious examples are Hero, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, House of Flying Daggers, The Forbidden Kingdom and Curse of the Golden Flower, which together mark a major shift from the low-budget, art-house films for which China was previously known. The blockbuster movies are generally historical dramas set in one of the early dynasties, drawing on China ’s rich history and punctuated with dramatic martial arts sequences. [1313] Not surprisingly, the storylines and approaches of Hollywood and Chinese movies differ considerably, reflecting their distinctive cultures. While Hollywood emphasizes the happy ending, this is never a major concern for Chinese films; action ranks highly for Hollywood, martial arts for the Chinese; cinematic realism matters for the US, social realism for Chinese audiences. In the longer run the Chinese film industry is likely to challenge the global hegemony of Hollywood and embody a distinctive set of values. It also seems likely that, in the manner of Sony’s takeover of Columbia, Chinese companies will, in time, acquire Hollywood studios, though this will probably have little effect on their output of Hollywood-style movies. [1314]

It is worth noting in this context the extraordinary influence that martial arts already enjoy in the West. Fifty years ago the pugilistic imagination of Western children was overwhelmingly dominated by boxing and, to a much lesser extent, wrestling. That picture has completely changed since the 1970s. The Western pugilistic traditions have been replaced by those of East Asia, and in particular China, Japan and Korea, in the form of tae kwon do, judo and kung fu, while amongst older people t’ai chi has also grown in influence. The long-term popularity of martial arts is a striking example of how in the playground and gym certain East Asian traditions and practices have already supplanted those of the West. [1315]

The economic rise of China, and of Chinese communities around the world, is changing the face of the market for Chinese art. Chinese buyers are now as numerous as Western ones at the growing number of New York and London auctions of Chinese art, a genre which, until a few years ago, was largely neglected by the international art market. In 2006 Sotheby’s and Christie’s, the world’s biggest auction houses, sold $190 million worth of contemporary Asian art, most of it Chinese, in a series of record-breaking auctions in New York, London and Hong Kong. At the end of that year a painting by contemporary artist Liu Xiaodong was sold to a Chinese entrepreneur for $2.7 million at a Beijing auction, the highest price ever paid for a piece by a Chinese artist. With auction sales of $23.6 million in 2006, Zhang Xiaogang was second only narrowly to Jean-Michel Basquiat in the ArtPrice ranking of the 100 top-selling artists in the world: altogether there were twenty-four Chinese artists in the list, up from barely any five years ago. These changes reflect the growing global influence of Chinese art and artists. [1316]

[1308] David Shambaugh, ‘ China Engages Asia: Reshaping the Regional Order’, International Security, 29: 3 (Winter 2004/5), p. 78.

[1309] ‘Students Again Make Beeline to US Colleges’, 5 April 2006, posted on http://English.peopledaily.com.cn.

[1310] Howard W. French, ‘China Luring Scholars to Make Universities Great’, New York Times, 28 October 2008; Arian Eunjung Cha, ‘Opportunities in China Lure Scientists Home’, Washington Post Foreign Service, 20 February 2008.

[1312] Michael Curtin, Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), p. 3; also p. 10.

[1313] Steve Rose, ‘The Great Fall of China’, Guardian, 1 August 2002; interview with Gong Li, ‘I Don’t Go to Hollywood. Hollywood Goes to China ’, Guardian, 6 April 2007; David Barboza, ‘Made-in-China Blockbusters: Success that Can Sting’, International Herald Tribune, 29 June 2007; Mark Landler, ‘Pa per Tigers, Hidden Knockoffs Flood Market’, International Herald Tribune, 4 July 2001.

[1314] See Gary Gang Xu, Sinascape: Contemporary Chinese Cinema (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007).

[1316] David Barboza, ‘At Christie’s Auction, New Records for Chinese Art’, International Herald Tribune, 29 November 2006; David Barboza, ‘In China’s New Revolution, Art Greets Capitalism’, International Herald Tribune, 4 January 2007; Jonathan Watts, ‘Once Hated, Now Fêted — Chinese Artists Come Out From Behind the Wall’, Guardian, 11 April 2007; Souren Melikian, ‘The Chinese Advance: More Bids, Many Buys’, International Herald Tribune, 8–9 April 2006.