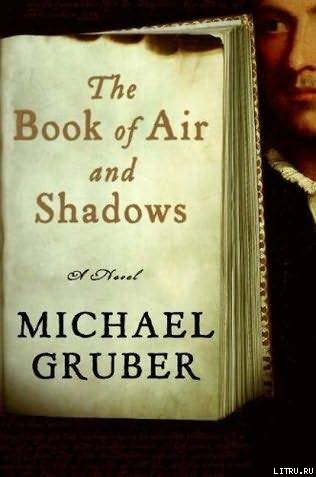

Michael Gruber

The Book of Air and Shadows

© 2007

For E.W.N.

Our Revels now are ended: These our actors (As I foretold you) were all Spirits, and Are melted into Ayre, into thin Ayre, And like the baselesse fabricke of this vision The Clowd-capt Towres, the gorgeous Pallaces, The solemne Temples, the great Globe it selfe, Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve, And like this insubstantial Pageant faded Leave not a racke behinde: we are such stuffe As dreames are made on; and our little life Is rounded with a sleepe… -WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE,

The Tempest, act IV, scene i,

The First Folio, 1623

1

Tap-tapping the keys and out come the words on this little screen, and who will read them I hardly know. I could be dead by the time anyone actually sees this, as dead as, say, Tolstoy. Or Shakespeare. Does it matter, when you read, if the person who wrote still lives? It sort of does, I think. If you read something by a living writer, you could, at least in theory, dash off a letter, establish a relationship maybe. I think a lot of readers feel this way. Some readers write to fictional characters as well, which is a little spookier.

But clearly I am not dead yet, although this could change at any moment, one reason why I’m writing this down. It’s a fact of writing that the writer never knows the fate of the text he’s grinding out, paper being good for so many uses other than displaying words in ordered array, nor are the tiny electromagnetic charges I am creating on this laptop machine immune to the insults of time. Bracegirdle is definitely dead, having succumbed to wounds received at the battle of Edgehill in the English Civil War, sometime in late October of 1642. We think. But dead nevertheless, although before dying he composed the fifty-two-page manuscript that has more or less screwed up my life, or killed me, I don’t know which yet. Or maybe the little professor was more to blame, Andrew Bulstrode, because he dropped the thing in my lap and then got himself murdered, or I could blame Mickey Haas, my old college roomie, who turned Bulstrode on to me. Mickey’s still alive as far as I know, or the girl, the woman I should say, she has to carry some freight for this, because I seriously doubt I would have plunged as I did if I had not spied her long white neck rising from her collar there in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room of the New York Public Library, and wanted to kiss it so much it made my jaw hurt.

And Albert Crosetti and his unusual mom and his even more remarkable girlfriend, Carolyn, if girlfriend she is, all discoverers, and explicators, and decipherers, of Bracegirdle, my nemesis, without whom…

I don’t forget the actual villains, but I can’t really blame them. Villains are just there, like rust, dull and almost chemical in the stupid simplicity of their greed or pride. Remarkable how easy it is to avoid these, how often we fail to do so. Not to mention Mary, Queen of Scots (speaking of stupid), one more conspiracy added to her score, even if all she did in this case was to exist. Naturally, I blame my dad, the old crook. And why not? I blame him for everything else.

I see I am not doing this right. Okay, regain focus, at least array the facts, and begin by identifying the writer, me, Jake Mishkin, by profession an intellectual property lawyer. I believe that some gangsters may in the near future attempt to kill me. Although there is a kind of lawyer who can reasonably expect a certain level of physical danger as part of the employment picture, I am not that kind of lawyer-by design, actually. In my youth, I was familiar enough with such lawyers; a few of them, I have reason to believe, actually did get whacked, and so when I chose my field of law I made sure it was one in which the ordinary participants did not routinely pack heat. IP law has its share of violent lunatics (perhaps more than its share), but when they scream obscenities and threaten to kill you and your client, they are, almost all the time, speaking figuratively.

Even then, much of this venom is directed at litigators, and I am not a litigator. I don’t have the personality for it, being a large peaceful person who believes that nearly all lawsuits, especially those involving intellectual property, are stupid, often grotesquely so, and that the underlying issues in virtually all of them could be solved by reasonable people in twenty minutes of conversation. This is not the mind-set of a successful litigator. Ed Geller, our senior partner, is a litigator: he is a pugnacious, aggressive, flamboyant, obnoxious little man, a being who might have served as the template for any nasty lawyer joke, yet to my certain knowledge, Ed (an individual for whom I have, by the way, the utmost professional respect) has never heard the snap of a bullet fired at him with bad intent, or tussled with thugs bent on robbery, both of which are now part of my life experience.

I should say that IP law is divided broadly into industrial, which covers trademarks and patents, and probably software fits in this class too, and copyright, which covers all the arts of humanity-music, writing, films, images of all kinds, Mickey Mouse, etc., and I will record here the instinctive punch of the special key on my machine that adds the sacred © to the little rodent’s name, and which I have just gone back and removed, because this is a new me writing this whatever it is. My firm, Geller Linz Grossbart & Mishkin, is a copyright house, and although each of the partners handles the full spectrum of copyright work, you could make a case that each of us has a different specialty. Marty Linz does TV and movies, Shelly Grossbart does music, Ed Geller is, as I said, our litigation chief. And I handle the literary business, which means I spend a good deal of time with writers, enough to realize that I am not and will never be one of their number. Quite a few of my clients have told me, often with a patronizing tone, that within every lawyer is a strangled poet, attributing the quotation to a variety of different authors. I don’t really mind this sort of thing, since all these people are as helpless as kittens in the real, as opposed to the imaginary, universe. I can do cutting irony too, when I choose, which is not that often because, in all honesty, I admire the hell out of them. I mean, just making up a story out of your head and writing it so that someone else, a complete stranger, can read it and understand it and have real feelings about fictitious persons! Were you ever so unfortunate as to have a seat on a packed-tight plane or train where you were stuck in front of a couple of jerks exchanging anecdotes? You want to cut your throat out of sheer boredom, right? Or kill them. My point is, at the risk of repeating myself, it’s damn hard to tell a coherent story. One client of mine told me that in order to write a story you start with everything that ever happened to anyone and carve away the parts that don’t fit. This was a joke, however. Although I seem to be doing something like it now.

Perhaps, though, I am being too diffident. The legal profession is not without its creative side. We do a lot of writing, nearly all of it of interest only to other lawyers, but still there is the business of telling a story, setting a scene, laying out the facts and assumptions behind one’s case. Young Charles Dickens started out as a court reporter, and scholars believe that this experience formed the sense of the human drama evident in his novels. Besides which, those novels are nearly all about crimes, mainly of the white-collar type. Mickey Haas is my source for that factoid, and he should know, as he is a professor of English literature at Columbia. And he is also the beginning of this story.