“She’s not dead,” Stephen said. “Just fainted.”

Lydia got down on the grass, cradled Charlotte’s head in her lap and felt her chest beneath her left breast. There was a strong heartbeat.

“Oh, my baby,” Lydia said.

Stephen sat beside her. She looked at him. His trousers had burned and his skin was black and blistered. But he was alive.

She looked toward the door.

Stephen saw her glance.

Lydia became aware that Churchill and Thomson were standing near, listening.

Stephen took Lydia’s hand. “He saved her,” he said. “Then he passed her to me. Then the floor fell in. He’s dead.”

Lydia’s eyes filled with tears. Stephen saw, and squeezed her hand. He said: “I saw his face as he fell. I don’t think I’ll ever forget it, as long as I live. You see, his eyes were open, and he was conscious, but-he wasn’t frightened. In fact he looked… satisfied.”

The tears streamed down Lydia’s face.

Churchill spoke to Thomson. “Get rid of the body of Orlov.”

Poor Aleks, Lydia thought, and she cried for him too.

Thomson said incredulously: “What?”

Churchill said: “Hide it, bury it, throw it into the fire. I don’t care how you do it. I just want you to get rid of that body.”

Lydia stared at him aghast, and through a film of tears she saw him take a sheaf of papers from the pocket of his dressing gown.

“The agreement is signed,” Churchill said. “The Czar will be told that Orlov died by accident, in the fire that burned down Walden Hall. Orlov was not murdered, do you understand? There was no assassin.” He looked around at each of them with his aggressive, pudgy face set in a fierce scowl. “There was never anybody called Feliks.”

Stephen stood up and went over to where Aleks’s body lay. Someone had covered his face. Lydia heard Stephen say: “Aleks, my boy… what am I going to say to your mother?” He bent down and folded the hands over the hole in the chest.

Lydia looked at the fire, burning down all those years of history, consuming the past.

Stephen came over and stood beside her. He whispered: “There was never anybody called Feliks.”

She looked up at him. Behind him, the sky in the east was pearly gray. Soon the sun would rise, and it would be a new day.

EPILOGUE

On August 2, 1914, Germany invaded Belgium. Within days the German army was sweeping through France. Toward the end of August, when it seemed that Paris might fall, vital German troops were withdrawn from France to defend Germany against a Russian invasion from the east; and Paris did not fall.

In 1915 the Russians were officially given control of Constantinople and the Bosporus.

Many of the young men Charlotte had danced with at Belinda’s ball were killed in France. Freddie Chalfont died at Ypres. Peter came home shell-shocked. Charlotte trained as a nurse and went to the front.

In 1916 Lydia gave birth to a boy. The delivery was expected to be difficult because of her age, but in the event there were no problems. They called the boy Aleks.

Charlotte caught pneumonia in 1917 and was sent home. During her convalescence she translated The Captain’s Daughter by Pushkin into English.

After the war the women got the vote. Lloyd George became Prime Minister. Basil Thomson got a knighthood.

Charlotte married a young officer she had nursed in France. The war had made him a pacifist and a socialist, and he was one of the first Labor Members of Parliament. Charlotte became the leading English translator of nineteenth-century Russian fiction. In 1931 the two of them went to Moscow and came home declaring that the USSR was a workers’ paradise. They changed their minds at the time of the Nazi-Soviet pact. Charlotte’s husband was a junior minister in the Labor government of 1945.

Charlotte is still alive. She lives in a cottage on what used to be the Home Farm. The cottage was built by her father for his bailiff, and it is a spacious, sturdy house full of comfortable furniture and bright fabrics. The Home Farm is now a housing estate, but Charlotte likes to be surrounded by people. Walden Hall was rebuilt by Lutyens and is now owned by the son of Aleks Walden.

Charlotte is sometimes a little confused about the recent past but she remembers the summer of 1914 as if it were yesterday. A rather distant look comes into those sad brown eyes, and she’s off on one of her hair-raising stories.

She’s not all memories, though. She denounces the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for giving socialism a bad name and Margaret Thatcher for giving feminism a bad name. If you tell her that Mrs. Thatcher is no feminist, she will say that Brezhnev is no socialist.

She doesn’t translate anymore, of course, but she is reading The Gulag Archipelago in the original Russian. She says Solzhenitsyn is self-righteous but she’s determined to finish the book. As she can read only for half an hour in the morning and half an hour in the afternoon, she calculates that she will be ninety-nine by the time she gets to the end.

Somehow I think she’ll make it.

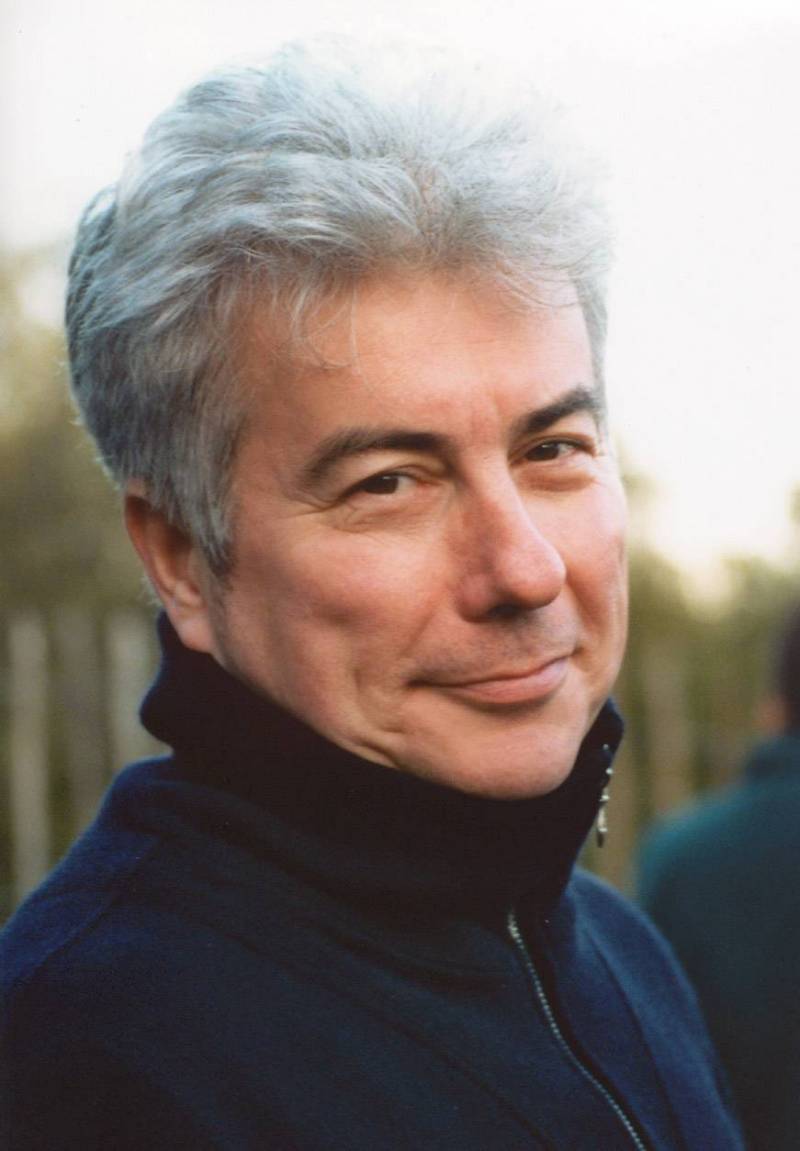

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ken Follett is the international bestselling author of suspense thrillers and the nonfiction On Wings of Eagles. He lives in England.

Visit Ken Follett’s official Web site at www.ken-follett.com.