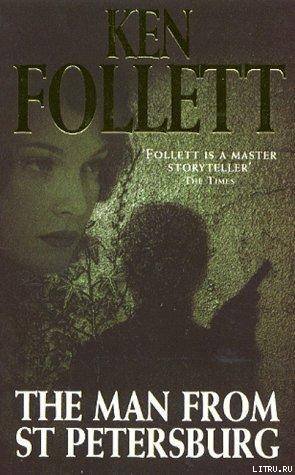

Ken Follett

The Man From St. Petersburg

© 1982

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In writing this book I was helped by many friends. My grateful thanks to Alan Earney, Pat Golbitz, M. E. Hirsh, Elaine Koster, Diana Levine, Caren Meyer and her moles, Sue Rapp, Pamela Robinson and the staff of Bertram Rota Ltd., Hilary Ross, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, Daniel Starer, Colin Tennant, and-alphabetically last but in every other way first-Al Zuckerman.

“One can’t love humanity. One can only love people.”

– GRAHAM GREENE

ONE

It was a slow Sunday afternoon, the kind Walden loved. He stood at an open window and looked across the park. The broad, level lawn was dotted with mature trees: a Scotch pine, a pair of mighty oaks, several chestnuts and a willow like a head of girlish curls. The sun was high and the trees cast dark, cool shadows. The birds were silent, but a hum of contented bees came from the flowering creeper beside the window. The house was still, too. Most of the servants had the afternoon off. The only weekend guests were Walden’s brother George, George’s wife, Clarissa, and their children. George had gone for a walk, Clarissa was lying down and the children were out of sight. Walden was comfortable: he had worn a frock coat to church, of course, and in an hour or two he would put on his white tie and tails for dinner, but in the meantime he was at ease in a tweed suit and a soft-collared shirt. Now, he thought, if only Lydia will play the piano tonight, it will have been a perfect day.

He turned to his wife. “Will you play, after dinner?”

Lydia smiled. “If you like.”

Walden heard a noise and turned back to the window. At the far end of the drive, a quarter of a mile away, a motor car appeared. Walden felt a twinge of irritation, like the sly stab of pain in his right leg before a rainstorm. Why should a car annoy me? he thought. He was not against motor cars-he owned a Lanchester and used it regularly to travel to and from London-although in the summer they were a terrible nuisance to the village, sending up clouds of dust from the unpaved road as they roared through. He was thinking of putting down a couple of hundred yards of tarmacadam along the street. Ordinarily he would not have hesitated, but the roads had not been his responsibility since 1909 when Lloyd George had set up the Roads Boards-and that, he realized, was the source of his irritation. It had been a characteristic piece of Liberal legislation: they took money from Walden in order to do themselves what he would have done anyway; then they failed to do it. I suppose I’ll pave the road myself in the end, he thought; it’s just annoying to pay for it twice.

The motor car turned into the gravel forecourt and came to a noisy, shuddering halt opposite the south door. Exhaust fumes drifted in at the window, and Walden held his breath. The driver got out, wearing a helmet, goggles and a heavy motoring coat, and opened the door for the passenger. A short man in a black coat and a black felt hat stepped down from the car. Walden recognized the man and his heart sank: the peaceful summer afternoon was over.

“It’s Winston Churchill,” he said.

Lydia said: “How embarrassing.”

The man just refused to be snubbed. On Thursday he had sent a note, which Walden had ignored. On Friday he had called on Walden at his London house and had been told that the Earl was not at home. Now he had driven all the way to Norfolk on a Sunday. He would be turned away again. Does he think his stubbornness is impressive? Walden wondered.

He hated to be rude to people, but Churchill deserved it. The Liberal government, in which Churchill was a minister, was engaged in a vicious attack on the very foundations of English society-taxing landed property, undermining the House of Lords, trying to give Ireland away to the Catholics, emasculating the Royal Navy and yielding to the blackmail of trade unions and damned socialists. Walden and his friends would not shake hands with such people.

The door opened and Pritchard came into the room. He was a tall Cockney with brilliantined black hair and an air of gravity which was transparently fake. He had run away to sea as a boy and had jumped ship in East Africa. Walden, there on safari, had hired him to supervise the native porters, and they had been together ever since. Now Pritchard was Walden’s majordomo, traveling with him from one house to another, and as much of a friend as a servant could be.

“The First Lord of the Admiralty is here, my lord,” Pritchard said.

“I’m not at home,” Walden said.

Pritchard looked uncomfortable. He was not used to throwing out Cabinet ministers. My father’s butler would have done it without turning a hair, Walden thought, but old Thomson is graciously retired, growing roses in the garden of that little cottage in the village, and somehow Pritchard has never acquired that unassailable dignity.

Pritchard began to drop his aitches, a sign that he was either very relaxed or very tense. “Mr. Churchill said you’d say not at ’ome, my lord, and ’e said to give you this letter.” He proffered an envelope on a tray.

Walden did not like to be pushed. He said crossly: “Give it back to him-” Then he stopped and looked again at the handwriting on the envelope. There was something familiar about the large, clear, sloping letters.

“Oh, dear,” said Walden.

He took the envelope, opened it and drew out a single sheet of heavy white paper, folded once. At the top was the royal crest, printed in red. Walden read:

Buckingham Palace

May 1st, 1914

My dear Walden,

You will see young Winston.

George R.I.

“It’s from the King,” Walden said to Lydia.

He was so embarrassed that he flushed. It was frightfully bad form to drag the King into something like this. Walden felt like a schoolboy who is told to stop quarreling and get on with his prep. For a moment he was tempted to defy the King. But the consequences… Lydia would no longer be received by the Queen, people would be unable to invite the Waldens to parties at which a member of the Royal Family would be present and-worst of all-Walden’s daughter, Charlotte, could not be presented at court as a debutante. The family’s social life would be wrecked. They might as well go and live in another country. No, there was no question of disobeying the King.

Walden sighed. Churchill had defeated him. In a way it was a relief, for now he could break ranks and no one could blame him. Letter from the King, old boy, he would say in explanation; nothing to be done, you know.

“Ask Mr. Churchill to come in,” he said to Pritchard.

He handed the letter to Lydia. The Liberals really did not understand how the monarchy was supposed to work, he reflected. He murmured: “The King is just not firm enough with these people.”

Lydia said: “This is becoming awfully boring.”

She was not bored at all, Walden thought; in fact, she probably found it all quite exciting; but she said that because it was the kind of thing an English countess would say, and since she was not English but Russian, she liked to say typically English things, the way a man speaking French would say alors and hein? a lot.

Walden went to the window. Churchill’s motor car was still rattling and smoking in the forecourt. The driver stood beside it, with one hand on the door, as if he had to hold it like a horse to stop it from wandering away. A few servants were gazing at it from a safe distance.