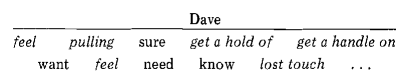

Of the ten predicates listed above used by Dave, more than half of them presuppose a kinesthetic representational system — that is, Dave organizes his experience, his model of the world, by feelings. Thus, Dave's most used representational system is kinesthetic. The remaining predicates used by Dave are consistent with this statement, as they are unspecified with respect to representational system.

Knowing a person's most used representational system is, in our experience, a very useful piece of information. One way in which we have found this useful is in our ability to establish effective communication. As therapists, if we can be sensitive to the most used representational system of the person with whom we are working, we then have the choice of translating our communication into his system. Thus, he comes to trust us as we demonstrate that we understand his ongoing experience by, for example, changing our predicates to match his. Being explicit about how the other person organizes his or her experience of the world allows us to avoid some of the typical "resistant client—frustrated therapist" patterns such as those described in Part I, The Structure of Magic, II, Grinder and Bandler:

We have in past years (during in-service training seminars) noticed therapists who asked questions of the people they worked with with no knowledge of representational systems used. They typically use only predicates of their own most highly valued representational systems. This is an example:

Visual Person: My husband just doesn't see me as a valuable person.

Therapist: How do you feel about that?

Visual Person: What?

Therapist: How do you feel about your husband's not feeling that you're a person?

This session went around and around until the therapist came out and said to the authors:

I feel frustrated; this woman is just giving me a hard time. She's resisting everything I do.

We have heard and seen many long, valuable hours wasted in this form of miscommunication by therapists with the people they work with. . . . The therapist in the above transcript was really trying to help and the person with him was really trying to cooperate but without either of them having a sensitivity to representational systems. Communication between people under these conditions is usually haphazard and tedious. The result is often name calling when a person attempts to communicate with someone who uses different predicates.

Typically, kinesthetics complain that auditory and visual people are insensitive. Visuals complain the auditories don't pay attention to them because they don't make eye contact during the conversation. Auditory people complain that kinesthetics don't listen, etc. The outcome is usually that one group comes to consider the other as deliberately bad or mischievous or pathological.

The point we are illustrating here is that one of the most powerful skills we, as therapists, can develop is the ability to be sensitive to representational systems. For change to occur, for the persons with whom we are working to be willing to take risks, for them to come to trust us as guides for change, they must be convinced that we understand their experience and can communicate with them about it. In other words, we accept as our responsibility as people-helpers the task of making contact with the persons we are trying to help. Once we have made contact — by matching representational systems, for example — we can assist them in expanding their choices about representing their experience and communicating about it. This second step — that of leading the individual toward new dimensions of experience — is very important. So often, in our experience, family members have "specialized" — one paying primary attention to the visual representation of experience, another to the kinesthetic portion of experience, etc.

For example, we discover from the transcript that Dave's primary representational system is kinesthetic, while Marcie's is visual. Once we have made contact, we work to assist Dave in developing his ability to explore the visual dimensions of his experience and to assist Marcie, in getting in touch with body sensations.[15] There are two important results of this:

(a) Dave and Marcie learn to communicate effectively with one another.

(b) Each of them expands his/her choices about representing and communicating their experiences, thus becoming more developed human beings — more whole, more able to express and use their human potential.

Within the context of family therapy, by identifying each family member's most used representational system, the therapist learns what portions of the ongoing family experience is most available to each person there. Understanding this allows the therapist to know where, in the communication patterns of the family, to look for faulty communication, where the family members fail to communicate what they intend. For example, if one family member is primarily visual and another auditory, the family therapist will be alert to note how they communicate, how they give each other feedback. Under stress particularly, each of us tends to depend only upon our primary representational system. We come to accept a part of our experience as an equivalent for the whole — accepting, for example, only what we see as equivalent to what is totally available not only through our eyes but also through our skin, our ears, etc. This explains the close connection between representational systems and the kinds of Mind Reading and Complex Equivalences developed by family members.

At this point in the presentation of the patterns which we have identified as useful in organizing our experience in therapy, we are going to shift the way in which we present the transcript. We have identified the most important of the verbal patterns which are in our family therapy model and, with the presentation of the principle of representational systems, we have begun to move to the next level of patterns. Verbal communications and your ability to hear the distinctions which we have presented are very useful portions of an effective model for family therapy. These verbal patterns and your ability to respond systematically to them, however, constitute only a portion of the complete model. In the presentation of the transcript up to this point, we have confined ourselves to reporting the verbal patterns. In this way, we hoped to find a common reference point from which each of you could connect what we are describing with words here in this book with your own experience in therapy. We hoped that, by finding this common reference point, you would be able to utilize, immediately and dynamically in your work, the patterns which we have identified.

Now we move on to patterns at the next level of experience, patterns which have as one of their parts the verbal patterns which we have just identified.

15

This technique — adding representational systems — is meta-tactic II, discussed in Part I of The Structure of Magic, Volume II.