“As with all the distinctions in the model, this superscript distinction between internally and externally generated experience will be employed only when it is useful for the task for which it is to be used.”

In NLP, sensory systems have much more functional significance than is attributed to them by classical models in which the senses are regarded as passive input mechanisms. The sensory information or distinctions received through each of these systems initiate and/or modulate, via neural interconnections, an individual's behavioral processes and output. Each perceptual class forms a sensory–motor complex that becomes "response–able" for certain classes of behavior. These sensory–motor complexes are called representational systems in NLP.[8]

Each representational system forms a three part network: 1) input, 2) representation/processing and 3) output. The first stage, input, involves gathering information and getting feedback from the environment (both internal and external). Representation/processing includes the mapping of the environment and the establishment of behavioral strategies such as learning, decisionmaking, information storage, etc. Output is the casual transform of the representational mapping process.

"Behavior" in neurolinguistic programming refers to activity within any representational system complex at any of these stages. The acts of seeing, listening or feeling are behavior. So is "thinking," which, if broken down to its constituent parts, would include sensory specific processes like seeing in the mind's eye, listening to internal dialogue, hawing feelings about something and so on. All output, of course, is behavior—ranging from micro–behavioral outputs such as lateral eye movements, tonal shifts in the voice and breathing rates to macro–behavioral outputs such as arguing, disease and kicking a football.

Our representational systems form the structural elements of our own behavioral models. The behavioral "vocabulary" of human beings consists of all the experiential content generated, either internally or from external sources, through the sensory channels during our lives. The maps or models that we use to guide our behavior are developed from the ordering of this experience into patterned sequences or "behavioral phrases," so to speak. The formal patterns of these sequences of representations are called strategies in neurolinguistic programming.

The way we sequence representations through our strategies will dictate the significance that a particular representation will have in our behavior, just as the sequencing of words in a sentence will determine the meaning of particular words. A specific representation in itself is relatively meaningless. What is important is how that representation functions in the context of a strategy in an individual's behavior.

Imagine a young man wearing a white smock, sitting in a comfortable position, sunlight streaming through a high window to his right and behind him. To his left is a red book with silver lettering on its cover. As we look closer, we see him staring at a large white sheet of paper, the pupils of his eyes dilated, his facial muscles slack and unmoving, his shoulder muscles slightly tense while the rest of his body is at rest. His breathing is shallow, high in his chest and regular. Who is this person?

From the description he could be a physicist, visualizing a series of complex mathematical expressions which describe the physical phenomena he wishes to understand. Equally consistent with the above, the young man could be an artist, creating vivid visual fantasies in preparation for executing an oil painting. Or, the man could be a schizophrenic, consumed in a world of inner imagery so completely that he has lost his connection with the outside world.

What links these three men is that each is employing the same representational system — attending to internal visual images. What distinguishes them from one another is how each utilizes his rich inner experience of imagery. The physicist may in a moment look up to a fellow scientist and translate his images into words, . communicating through his colleague's auditory system some new pattern he's discovered through his visualizations. The artist may in a moment seize the white sheet of paper and begin to rough in shapes and colors with a brush — many of them drawn directly from his inner imagery — translating inner experience into external experience. The schizophrenic may continue his internal visual reverie with such complete absorption that the images he creates within will distract him from responding to sensory information arriving from the outside world.

The physicist and the artist differ from the schizophrenic in terms of the function of their visualizations in the context of the sequence of representational system activities that affect the outcome of their behavior: in how their visualizations are utilized. The physicist and the artist can choose to attend visually to the world outside or to their own inner visual experience. The process of creating inner visual experience is the same, neurologically, for all three men. A visual representation in itself — like the waterfall or the mold on the bread previously discussed — may serve as a limitation or a resource to human potential depending on how it fits into context and how it is used. The physicist and the artist control the process; the process controls the schizophrenic. For the physicist and the artist, the natural phenomenon of visualization belongs to the class of decision variables; for the schizophrenic it belongs to the class of environmental variables.

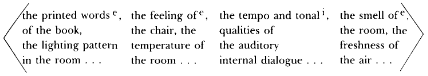

Each of you reading this sentence has a strategy for taking the peculiar patterns of black ink on this white page and making meaning out of them for yourself. These sequences of letters, like the other visualization phenomena just described, are meaningless outside of the sensory experiences from your own personal history that you apply to them. Words, both written and spoken, are simply codes that trigger primary sensory representations in us. A word that we have never seen or heard before will have no meaning to us because we have no sensory experience to apply to it. (For a further discussion of language as secondary experience see Patterns II.)

As you read these words you may, for example, be hearing your own voice inside your head saying the words as your eye reports the visual patterns formed by letters in this sentence. Perhaps you are remembering words that someone else has spoken to you before that sounded similar to those printed here. Perhaps these visual patterns have accessed some feelings of delight or recognition within you. You may have noticed, when you first read the description of the young man in the white smock, that you made images of what you were reading—you were using the same representational strategy for making meaning that the young man in our description was using.

The ability to transform printed symbols into internal images, into auditory representations, into feelings, tastes or smells, allows us to use strategies for making meaning that are available to each of us as human beings. Certain strategies are highly effective for creating meaning in certain contexts while others are more effective for other tasks. The strategy of taking external visual symbols and translating them into internal auditory dialogue would not be appropriate if you were listening to a record, doing therapy or playing football.

This book presents what we call meta–strategies: strategies about strategies. More specifically, this book describes how to elicit, identify, utilize, design and install strategies that allow us to operate within and upon our environment. NLP is an explicit meta–strategy designed for you — to shift dimensions of your experience from the class of environmental variables to the class of decision variables and, when appropriate, to assist others to do so. NLP is an explicit meta–strategy by means of which you may gain control over portions of your experience which you desire to control, an explicit meta–strategy for you to use to create choices that you presently don't have and to assist others in securing the choices they need or want.

8

The concept of representational systems and various methods of utilization have been discussed at length in other of our works. Specifically, The Structure of Magic Volume II, Patterns of the Hypnotic Techniques of Milton H. Erickson M.D. Volumes I & II, and Changing with Families Volume I.