(C relates that her primary motivation for keeping her weight down had come from external sources — specifically, her mother (who, judging by C's accessing cues, was probably the source of C's current internal dialogue about eating).)

A: You didn't have to rely much on your own resources?

C: No ... I didn't have much choice in what was going on with my life (eyes back and forth between down left and down right) ... it really wasn't a very happy time in my life . . .

In response to the results of his inquiries, the author decides to abandon his search for applicable resources from C's personal history (since her relevant reference structures all appear to be associated with negative 4-tuples) and decides to opt for artificial design. Given the information he has gathered, it is evident that some specific conditions the strategy will have to meet will be (1) that C's motivation strategy for controlling her weight will need to include all representational systems, and (2) that the weight control strategy will have to be initiated before C has hooked into her motivation strategy for overeating. (3) C's test for knowing when she's had enough to eat operates only from external feedback (Ve) and does not involve any internal check (this, as we mentioned above, is probably a result of the programming done by C's mother). The result is that the test, though probably accurate, initiates no internal intervention (it is missing the operate phase). The author, then, must be sure to design such an operation into the strategy. (4) C has no representation of the desired state in the strategy, and, thus no means for obtaining feedback.

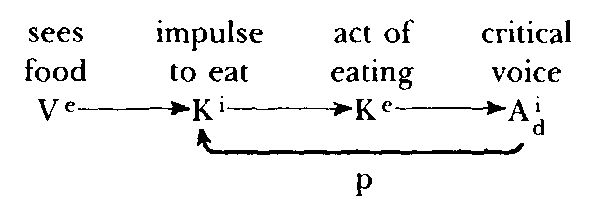

C's problem strategy was basically a polarity loop that cycled between the impulse to eat and an internal dialogue telling her not to:

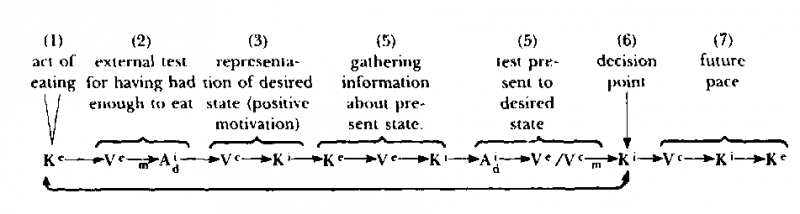

The new strategy designed by the author, separated into sections to aid the reader in following its structure, was sequenced as follows:

(1) C begins, of course, with the act of eating.

(2) This will trigger her naturally occurring strategy to assess, by watching what she eats, when she's had enough. It is at this point that the author chose to install the new strategy sequence, as it is just before the problem loop starts. In addition to the feedback that she has eaten enough, (an internal step is established later in the strategy) the author added another verbalization to the internal dialogue that went, "I've had plenty to eat and if I stop eating now I'll be able to get skinnier." (This verbalization was rehearsed a number of times in conjunction with C's existing response.)

(3) This verbalization was to anchor a step in which C made a constructed image of herself the way she would like to look (Vc). This image was, in turn, to access the experience of how good it would feel to have accomplished the outcome that she had desired so long (Ki).

(4) As soon as she was able to get this feeling she was to immediately get up from the table (Ke) and go look at herself in a mirror. (She was given special instruction, if she did not have one already, to get a full length mirror and hang it in the kitchen, if possible, or in a room close by.) This step had an added advantage in that it forced an interruption of her external visual contact with food. After she looked at herself closely, she was to close her eyes, take a deep breath and check out her feelings, and test if she had had enough to eat. This was to verify (or contradict) the earlier communication from her internal dialogue. This step was sequenced after she had interrupted her external visual contact with the food on the table to make sure that the feelings were uninfluenced by her Ve →Ki synesthesia pattern.

(5) C was then to comment on those feelings to herself, describing explicitly the feelings she experienced (note how this changes the role of her internal dialogue in her eating strategy — it is now describing the feelings as opposed to having a polarity response to them). After she had described the feelings, she was to ask herself if she wanted to eat more or to put everything away. In making this decision she was to compare the image of her desired state to what she observed of her present state (Ve/Vc) and allow a feeling to emerge to help her decide which it was to be.

(6) If she truly felt that she should have more to eat (which the author guessed would rarely be the case) she was to respect the decision of her feelings and eat, but first she was to construct a specific image of what else, and how much of it, she was to eat. If she didn't feel the need to eat, she was to imagine as if looking through her own eyes, in as much detail as possible, putting each of the items left on the table away, and then leaving the kitchen to do something else. As she imagined these scenes she was also to include the representation of feeling good, as she did the specific actions, about having accomplished her outcome successfully. (The use of the visual constructs was to provide a self initiated future pace that would help reprogram the problematic synesthesia pattern. The act of putting the food away or of eating only so much would be initiated by the sight of the food instead of the eating impulse. If she did go back to eat, the imagery would also help her "keep watch" over how much she was eating.

Various reference structures were accessed and anchored for each step in the strategy, and then the strategy was rehearsed. But, although C could elicit and perform each of the pieces of the strategy separately, she had an extremely difficult time getting through the whole strategy. Every time she tried, she would miss a step or something would go wrong. This, of course, does not satisfy the test step 1 of the reframing TOTE.

We pick up the transcript again just after C has made another attempt at completing the strategy. This puts the author and the client at 2B in the reframing TOTE.

C: Gee . . . I'm really sorry I keep bumbling things up ... I'm just too stupid or something I guess . . . (eyes down left, then down right).

A: Before you start feeling bad about anything I'd like to ask you a question.

C: Okay.

A: What would happen if you were able to incorporate this strategy?

(Having met with interference, the author moves to step #3 of the reframing TOTE, and tests the specific outcome sequitur of the strategy.)

C: Well ... I'd stop eating, I guess.

A: Well I hope you wouldn't stop eating, . . . that could be disastrous.

(A also tests his rapport with C by venturing a playful remark.)

C: (Laughing) Well I mean . . . I wouldn't stop eating altogether ... I'd stop over-eating . . .

(C responds positively indicating that rapport has not been broken. A continues to test the outcome in more detail. (Still step #3))

C: Ummm ... I'd be thinner ... I'd look thinner.

A: You'd look thinner.

C: Yes ... I'd look the way I want to to be able to . .. the way I did in college ... I want to look the way I did when I didn't like myself. . .

(C's last comment seems to imply a connection between the way C looked at an unhappy time in her life, and the kind of person she was. If she was indeed to not like herself again if she looked thinner, this would be in conflict with a very basic meta-outcome, that of liking oneself. In the least case, looking thinner is probably a bad anchor.)

A: Are you aware of what you just said?

C: What I said about what?

A: That you want to look like you did when you didn't like yourself.

C: Well . . . sort of . . .

A: I'm curious . . . How much have you changed since then . . . since you put on weight?