S: (S studies the blackboard for about five minutes and then his forefinger begins to raise.)

A: Okay . . . Good . . . Now here's the next step ... I want you to look at me . . . and I'm going to move my eyes around to a number of different positions . . . and I want you to watch me so that you can see very clearly (raises voice pitch— ∮1 Ae does not apply kinesthetic anchors) each position that I move my eyes to ... and as you see them I want you to comment explicitly to yourself (slows voice tempo— ∮2Ae) about which positions I'm accessing . . . and get in touch with your feeling and check out (deepens tonality- ∮ 3Ae) how good your grasp of them is . . . until you feel that you can not only see each position and know what it means but so you can see a whole sequence . . . and when you feel that you can do that I want you to allow your right hand to raise . . . (Note: A only anchors S through the strategy sequence once to test to make sure the strategy will access and perpetuate itself.)

S: (Watches A's eye movements for a few minutes and then raises his hand) . . . Okay . . .

A: Good . . . How is it working?

S: Fantastic . . . I've never felt so confident about any of this before.

A: Great . . . Now I'd like to test the effectiveness of your new learning strategy by running through a bunch of eye movement sequences and then have you tell me which sequence I just did . . . Okay . . . Begin . . .

S is able to follow each of the sequences the author presents. The strategy is then tested again by having S observe two other people from group interact until he is able to recount to the author the eye movement sequences of both people. He then gives S an anchor to access the strategy that S can initiate himself — that of S reaching over and squeezing his own forearm.

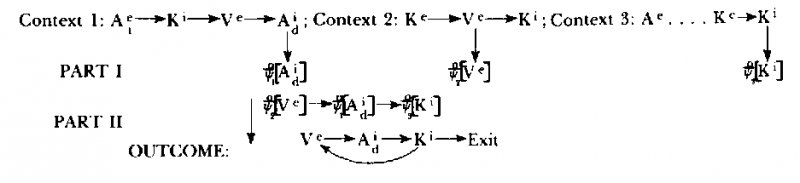

We can diagram the process of extracting and sequencing unrelated strategy steps in the following way:

6.2 Rehearsal

Rehearsal is a more operant method of conditioning or installing a strategy (as opposed to "anchoring" which more closely parallels classical or Pavlovian methods of conditioning). In the rehearsal process the individual practices or rehearses each representational step in the strategy until it becomes available as a spontaneous intact program. This process essentially involves the development of self-established anchors for strategy sequences.

6.21 Rehearsing Strategy Steps.

The most basic method of rehearsal would be that in which the programmer instructs the client in practicing making the transition through each step in the strategy as the programmer plugs in a number of different contents. This, of course, was a large part of what took place in the transcript.

Many times it won't take more than a few minutes of rehearsal to install a new strategy. Once one of the authors conducting an out-of-town workshop and was staying at the home of the workshop sponsor. While spending a quiet evening at the sponsor's home the author observed the sponsor's wife sitting with her second grade daughter and holding up flash cards with words and sentences on them for the girl to read and then spell. The daughter was obviously doing very poorly and consistently mixed up the orders of the words as she read and spelled. Taking an interest, the author asked the mother how her daughter was doing in school. Not surprisingly, the mother shook her head and admitted that her daughter was doing poorly, especially in reading. The daughter was constantly mixing up and reversing the orders of words, a condition that a specialist had diagnosed as dyslexic.

Reading, and especially spelling, from flash cards will generally require that the individual hold an internal visual image in the mind's eye. The author postulated that if the child had an underdeveloped visual system, it might account for the trouble. Judging by the child's body type, tonality and accessing cues, she should have been fully capable of making internal visual images. The author tested the girl's visual abilities by asking her to make and describe a series of images, which she could do readily. He then tested her reading and spelling strategies by flashing a card and asking her to read it and spell it. After looking at the card, the child's eyes immediately moved down and to the left, then, remaining down, over to the right, and back to the left, as she stumbled with the words — unable to achieve the outcome. It was immediately obvious to the author that it was the child's strategy for reading and spelling — an internal auditory and kinesthetic loop

—that was causing her so much trouble.

The author asked the child if she would like to play a flashcard game with him. This game was to be fun and she would not have to "try" to read or spell anything. She readily agreed. The author proceeded to show the child a flash card. As the author held the card and pointed to each letter in succession from left to right (Ve), the child was to pronounce each letter and sound each word out (Aed ). Then she was to look back at the entire word and pronounce it (Ve → Ae) out loud, and, then looking down and right and using her feelings (Ki), tell whether the sounds she made were a real word. If it didn't feel right, she was to look back at the entire string of letters and pronounce them again a different way, and feel that out. She would continue until she felt good about the pronunciation and the word. Every time she pronounced and read the word correctly the author would smile, say "Good" in an encouraging tonality and squeeze her wrist. The fun of the flashcard game came, however, when the author put the flashcard down, for he would then direct her to move her eyes up and left and keep looking up there until she could see the card he had just put down. She could imagine the letters any color she wanted and was especially invited to try her favorite color. When she could see the series of letters clearly she was then to read them off to the author —not "spell" the word, just read the letters off as she saw them. She was even allowed to see the author's finger moving from left to right if she got stuck. (This was her favorite part of the game.) After she had read them off she was to look back at the words in her mind's eye, change the color again if she wanted to, sound out the letters, look back at the whole sequence, pronounce the word and then move her head down and right to feel if she was correct. Again, at each successful completion of the step, she was given positive reinforcement tonally and with a smile; and the kinesthetic anchor on her wrist was reinforced.

A special surprise soon emerged into the game. After a few trials, if the child got stuck, the author could make the internal image or pronunciation appear in her head simply by squeezing her wrist. Eventually, the child herself could make any difficult word-picture or pronunciation appear by squeezing her own wrist.

Another positive aspect of the game was the surprise that was vocally and congruently expressed by the child's mother, who had never heard her read or spell so well. In the half hour spent with the author, playing the somewhat mysterious flashcard game, the child successfully made it through more fiashcards than they had previously been able to get through in days — and the child was eager to do more of them, as she had gotten quite good at it. In fact, the little girl at one point exclaimed, "This is a lot easier than what I do with Mommy!" Additionally, even though she would occasionally leave a word or letter out, the child did not once reverse a word or letter during the entire game. (It should be noted that the author stopped pointing to the letters after the first few cards he held up, for the child was soon able to imagine it there as she read.)