Rapport, like many other aspects of neurolinguistic programming, is quite subtle but extremely powerful in its implications and effects. Rapport of some kind is essential to any type of communication. Once you believe rapport has been established through pacing, you should continually test it to make sure you are staying appropriately attuned. The best way to do that is by attempting to "lead" the person. Once you have paced the person you are communicating with and believe you have established a secure rapport, violate your pace and change your behavior — that is, attempt to lead the person you have been pacing into a different behavior. If sufficient rapport and trust have been built up you can make this transition smoothly and easily. If the person doesn't follow you, return to pacing him until you have established the necessary rapport. If the person follows your lead, it will be important that you return to pacing him periodically to keep up rapport. Your leading may be as subtle as a shift in breathing rate, eye gaze, tonality or body posture. Make certain that it is sufficiently overt that you are sure you can observe the change.

The phenomenon of leading has, of course, other important implications as well. We have discussed these at length in Patterns I and II and in The Structure of Magic II.

4.23 Flexibility in Pacing Strategies

As you begin to explore your own strategies and those of clients and acquaintances, you will discover, as you pace and utilize the various steps and decision points, that some steps will be flexible and easy to pace while others will require much greater attention to the details of the contents of the representation. Some decision criteria will require generalization of the content of the representation while others will involve complex discrimination between the content details.

Many of the difficulties people experience with their strategies result from inappropriate or ineffective tests, or decision criteria. Some people are overly flexible or general and unable to discriminate, which can lead to leaving out or failing to gather important information. Others overly discriminate, often with result of missing important information which becomes lost in a sea of irrelevant "facts" (see the Design Section of this book for a more detailed discussion).

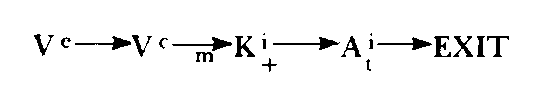

Your ability to pace successfully, then, may involve more or less attention to content detail as you are pacing or utilizing a particular strategy. As a general rule you will find that the more you can control the details of the content of the representations that occur in the strategy, the more you can control the details of the content of the outcome of the strategy — provided that you have successfully paced the sequence of representational systems in the strategy. For instance, in the sample motivation strategy in EXERCISE B:

If you want the individual to stand on his head, you will want to make sure that a constructed visual image is made of the act at step Vc. If the image is of something else you won't get your desired outcome. If you want him to stand on his head in the bathtub, as opposed to on the lawn outside, you should also detail that in the constructed image. If you want him to wiggle his toes while he is standing on his head, you should detail that, and so forth.

If, on the other hand, you want the individual to be motivated to carry out a more general task, like studying effectively for a test or watching his diet, you will want to be less specific with the details of the image.

In fact, bear in mind that, in many cases, trying to control the content details will interfere with your pacing of the person. Often the details you attempt to provide may be incongruent with those already being generated by the person with whom you are communicating. As with all of the other procedures we present in this book, the rule of modeling elegance applies here. That is, concern yourself with the details of the content of the strategy only as much as is required to get the outcome that you are after.

Another important area of flexibility in the pacing or utilization of strategies is that of substituting internally generated representations, within a representational system, for those that are typically generated from external sources, and vice versa. Because internally and externally generated experiences within the same representational system share the same neural pathways, you can often substitute one for the other as you are pacing or utilizing a strategy. Sometimes this capacity for substitution is a natural property of the strategy, at other times it will be new for that strategy. The same substitution can also be made, of course, for constructed versus remembered experiences. There will be times, however, when this substitution cannot be made because of the structure of the strategy.

What is important for the outcome of the strategy, of course, is the information carried by the representation.

Many of you readers can make internal images that you can see almost as vividly as you can see the words on this page. Others may be unaware of internal imagery unless you are in an altered state of consciousness, but in your normal state you can remember voices extremely clearly.

For some people, such as schizophrenics, the substitution between internal & external experience is all too easily made. For others, the inability to make these substitutions can be very limiting.

The ability to cross–substitute internally generated experience for externally generated experience, and constructed or imagined experience for remembered experience, is a valuable tool for the neurolinguistic programmer and a very valuable resource for your clients. Often when we are attempting to access or elicit experiences and representations from people, to be used as resources, they will respond something like, "I forget," "I don't know," or "I've never had that experience." In such cases we simply say, "Imagine what it would be like if you could (or did)." When a person's imagination or fantasies provide the same information as the actual experience, there is essentially no difference in the significance of the representations.

4.3 Anchoring — Accessing and Reaccessing Representations.

When it is important to control the content of a representational system, as when you are working with a decision point, you will need a way to assure easy access and reaccess to the particular representation associated with that decision point. This is accomplished in neurolinguistic programming through a procedure we call anchoring.

Most of you readers have had the experience, in communicating with a client, friend or associate, of reaching a certain level of rapport and understanding that was a very positive resource to both of you. Later on, however, the flow of the conversation, discussion or negotiation changes. The interaction becomes more tense, strained or difficult, and you wish you had a way of reaccessing the positive experiences that you shared before. Anchoring is a process that allows you to do this.

An anchor is, in essence, any representation (internally or externally generated) which triggers another representation, 4–tuple or series of representations or 4–tuples (i.e., a strategy). A

basic assumption behind anchoring is that all experiences are representated as gestalts of sensory information—4–tuples. Whenever any portion of a particular experience or 4–tuple is reintroduced, other portions of that experience will be reproduced to some degree. Any portion of a particular experience, then, may be used as an anchor to access another portion of that experience.