Within 72 hours of receiving the phone call, I was being ushered into General Akhtar’s house in Islamabad. As a soldier he looked impressive, with an immaculate uniform, three rows of medal ribbons and a strong physique. He had a pale skin and was intensely proud of the Afghan blood he had inherited. He carried his years well and I recall thinking he looked far younger than 59. He knew that I did not want the job, so he started by asking me how much I knew of the ISI’s role in the Afghan war. Apart from general rumours and the recent Quetta incident, I knew nothing, so he took considerable time to brief me, stressing that he had personally selected me for the job, and that his decision had the backing of the President. All very flattering, but I now knew the enormous responsibilities that I was about to shoulder. Like many of my contemporaries at that time, I was not convinced of the wisdom of our government’s policy on Afghanistan. I doubted whether the Soviets could be defeated militarily, and, with the presence of enormous numbers of refugees inside Pakistan, I felt that, sooner or later, we would face the same problems that some Arab countries were having from Palestinians on their soil, Within a few weeks I knew I was wrong.

In late 1983 Pakistan was a Muslim country under martial law. The Chief Martial Law Administrator was the President, Zia. There had been little exceptional about Zia the general, but Zia the politician was a shrewd and ruthless man. whose appearance belied his toughness. Benazir Bhutto once described him as ‘a short, nervous, ineffectual-looking man whose pomaded hair was parted in the middle and lacquered to his head”. I certainly recall that for the man who ruled Pakistan he seemed, on first acquaintance, somewhat inoffensive, always rising from his seat and coming forward to greet guests most effusively, never waiting for them to approach him. But those that underestimated him did so at their peril, the prime example being Benazir’s father.

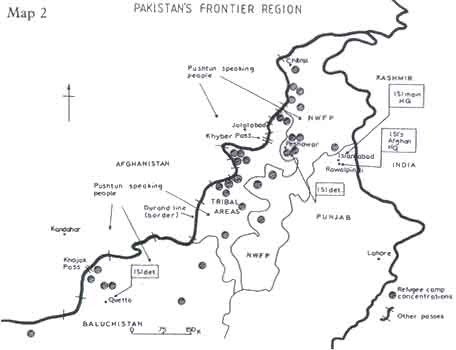

The Armed Forces governed the country and Zia controlled the Armed Forces, the senior ranks of whom he watched and manipulated cunningly to ensure his own survival. Each province in Pakistan was then under a military governor, a senior general who owed his appointment to the President. Of these the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and Baluchistan bordered Afghanistan. They were the front-line provinces, with a large proportion of the Pakistan Army deployed within their boundaries, watching the frontier, and able to move forward to previously reconnoitered battle positions should the Afghan war threaten to spill over the border. Pakistan felt insecure. India was on her eastern flank, an enormous nation of 800 million hostile Hindus, with whom Pakistan had fought three times. To the west lay Afghanistan and the Soviets, a communist superpower whose army was now deployed within easy reach of the mountain passes into Pakistan. Potentially, it was a highly dangerous strategic situation. India and the Soviet Union were allies; should they combine, Pakistan faced the prospect of being squeezed out of existence. I was fully aware of these threats. Like all officers, I knew that our military contingency plans were drawn up on the basis of fighting the Indians or, since 1979, the Soviets. Our nervousness was heightened by the fact that the USSR was a nuclear giant, and India had developed a nuclear capability, which we were seeking to emulate for obvious reasons of self-defence.

Pakistan’s position was further complicated by the long-standing dispute with India over Kashmir in the NE, the simmering troubles in Baluchistan were three was a breakaway independence movement, and the centuries-old instability of the NWFP (see Map 2). The NWFP had always been a tribal area which defied control by a central government. In 1983 a British bureaucrat called Sir Mortimer Durand demarcated a new border, thereafter called the Durand Line, between what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan. While this line gave every strategic advantage in terms of dominating heights to Pakistan (then part of India ), which suited imperial defense, it ignored tribal, ethnic or cultural realities. It cut through the Pushtun people’s homelands. Britain had never seriously sought to subdue these warring tribes and clans. Even those areas east of the Durand Line were left to their own devices in the mountains. The whole of the NWFP had been an armed camp for the British, every regiment in India had its tour on the frontier, where the Pushtun tribesmen provided excellent training for the military, with an endless stream of incidents, and sometimes full-scale punitive expeditions. It was much the same for Pakistan. The Pushtuns were never ruled by the British, and at independence Pakistan took over the timeless situation whereby local tribes in this area continued to control their own affairs, and to move to and for across the border much as they pleased. By and large we left them to get on with their trading and feuding without government intervention. The British had found this the easy option and so did Pakistan.

Into these frontier areas had poured a vast flood of refugees from Afghanistan. At that time over 2 million people had encamped along a 1500-kilometre stretch of border, from Chitral in the North to beyond Quetta in the south. Hundreds of tented and mud-hut camps teemed with people, mostly old men, women and children, all of whom were destitute. As will become clear later, the existence of these refugee camps played a key role in the struggle for Afghanistan.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December, 1979, Zia had immediately sent for his Director-General of the ISI, General Akhtar. He wanted an assessment of the situation facing Pakistan. He wanted answers to several questions, but most of all he wanted to know how he, Zia, should react. As a military man, he had turned, not to diplomats or politicians, but to a fellow soldier, a former military college classmate, for advice. He had told Akhtar to produce what soldiers call, ‘an appreciation of the situation’, but on a national, grand-strategy level. An appreciation is a meticulous, logical, step by step examination of a given situation, where all relevant factors are considered, along with likely enemy objectives, to produce a recommended course of action and an outline plan to achieve it.

Akhtar had made his presentation to Zia, forcefully recommending that Pakistan should back the Afghan resistance. He argued that not only would it be defending Islam but also Pakistan. The resistance must become a part of Pakistan’s forward defence against the Soviets. If they were allowed to occupy Afghanistan too easily, it would then be but short step to Pakistan, probably through Baluchistan Province. Akhtar made out a strong case for setting out to defeat the Soviets in a large-scale guerrilla war. He believed Afghanistan could be made into another Vietnam, with the Soviets in the shoes of the Americans. He urged Zia to take the military option. It would mean Pakistan covertly supporting the guerrillas with arms, ammunition, money, intelligence, training and operational advice. Above all it would entail offering the border areas of the NWFP and Baluchistan as a sanctuary for both the refugees and guerrillas, as without a secure, cross-border base no such campaign could succeed. Zia agreed.

The President told his Director-General to give him two years in which to consolidate his position in Pakistan and internationally. In 1979 Zia had just provoked worldwide consternation and condemnation by executing his former prime minister; his image both inside and outside Pakistan was badly tarnished, and he felt isolated. By supporting a Jehad, albeit unofficially, against a communist superpower he sought to regain sympathy in the west. The US would surely rally to his assistance. As a devout Muslim he was eager to offer help to his Islamic neighbours. That religious, strategic and political factors all seemed to point in the same direction was indeed a happy coincidence. For Zia, the final factor that decided him was Akhtar’s argument that it was a sound military proposition, provided the Soviets were not goaded into a direct confrontation, meaning the water must not get too hot. Zia stood to gain enormous prestige with the Arab would as a champion of Islam, and with the West as a champion against communist aggression.