General Beg, who had just avoided dying with his President, had circled the burning wreckage in his own aircraft before flying straight to Islamabad. There troops were alerted, key points protected, and a crisis cabinet meeting called. But there was no military takeover. Beg accepted immediate promotion to Zia’s old post of Army Chief of Staff, while the civilian chairman of the Senate, the 73-year-old Ghulam Ishaq Khan, took over as head of the interim government. The November election would go ahead.

Almost certainly the military authority that halted the autopsies will never be named, nor will the details of the collusion that must have taken place so swiftly between the Pakistani authorities and the US Embassy in Islamabad. It was not until ten months later that congressional pressure finally forced the State Department to allow three FBI investigators to go to Pakistan. As Congressman Bill Mclollum (R. Fla.) said, “At this late date, can the FBI find out what actually happened in Pakistan ? I don’t know. But we intend to find out what happened at the State Department”. The FBI team seemingly lacked enthusiasm for the task. It was reported that ‘awkward’ questions were not asked; the agents appeared disinclined to investigate evidence that conflicted with the statement that the bodies were too badly burned to permit autopsies and, with their schedule arranged by the Bhutto government, were apparently more interested in sightseeing than cross-questioning witnesses. According to a Washington Times source they only left Islamabad for tourist trips. Their attitude made it quite clear that they were following instructions not to stir the pot.

There was much hypocrisy in high places at the funeral on 20 August, 1988. India had sent its President and declared national mourning at home, the Russian Ambassador laid a wreath with solemn ceremonial, while US Secretary of State George Schultz called Zia a ‘martyr’ and assured the Mujahideen fundamentalist Leader, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, that the US would do all it could to ensure their success in freeing Afghanistan. The funeral had both a military and an Islamic flavour. Hundreds of thousands of Pakistanis gathered near the gold-plated Faisal Mosque to watch the coffin, covered in the national flag and flowers, and carried on the shoulders of soldiers, arrive for the final rites. Prayers were followed by the measured boom of a 21-gun salute.

There was genuine sorrow and foreboding among the three million Afghan refugees encamped just inside the Pakistan border. There was a great sense of loss among the Mujahideen, for Zia and Akhtar had been the architects of their successes in the field. Now, with the Soviets withdrawing, with victory in sight, continued, uninterrupted support would be indispensable for the final push to Kabul. As the reader will discover the Mujahideen were to be bitterly disappointed.

The Beginnings

“The water in Afghanistan must boil at the right temperature.”

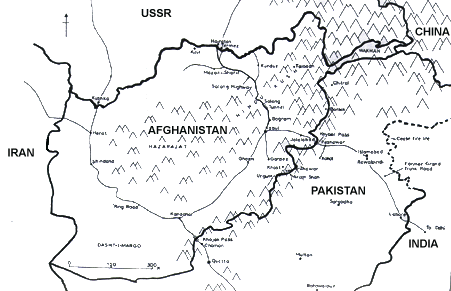

QUETTA is the capital of Baluchistan Province in Pakistan. My life as a soldier was completely changed because of Quetta, which has been a garrison town since the last quarter of the 19th century. Its name is a variation of the word ‘kwat-kot’, signifying a fortress, as it is the southernmost point in a line of frontier posts that date back to the days long before the partition of the Indian sub-continent into Pakistan and India in 1947. It grew from a dilapidated group of mud buildings into a thriving market community, and one of the most popular stations of the old British Indian Army. The military Staff College of Pakistan, which I had attended as a young major, was originally established at Quetta in 1907, and is today a college of international repute, with potential senior officers from many foreign countries competing for places. Students from Britain, Canada, Australia, the US, Egypt, Jordan, Thailand, Singapore, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere had all rubbed shoulders with me on the same course. The Quetta earthquake of 1935 flattened the town, killing some 40,000 people and making it the most destructive quake of modern times, until the June, 1990, one in northern Iran. Today it is an important Pakistan Army garrison town with a large military cantonment area housing numerous units and a corps headquarters. It is the centre of a base are for possible operations in Baluchistan, or along the border. A hundred kilometres to the NW, over the Khojak Pass, is the southern gateway into Afghanistan (see Map 1).

I was in Quetta when I received the telephone call that was to send me to my new posting with the ISI. It was September, 1983, and I was taking part in divisional war games as a brigade commander. Later, I learned that it was the so-called ‘Quetta incident’ that had resulted in that call being made. Some months before there had been a corruption scandal within the ISI, involving three Pakistani officers who had been arrested for accepting bribes from Mujahideen Commanders in exchange for the issue of extra weapons, well above their allocation. These arms would fetch high prices in the frontier areas of Pakistan. The officers were court-martialled and imprisoned, while the brigadier, whose job I was to take, was moved sideways. As I was soon to discover, Quetta housed a forward detachment of my new organization, the Afghan Bureau of the ISI.

I was told to fly to Islamabad immediately and report to the Director-General of ISI, Lieutenant-General Akhtar. To say I was apprehensive would be an understatement. I was filled with misgivings. I knew nothing of intelligence matters, my career had followed the clear-cut pattern of a regimental infantry officer, with tours of duty with my battalion alternating with operational staff jobs, then as a commanding officer. As a full colonel I was on the operations staff of a crops; at no stage had I had any intelligence experience. So why was I being summoned to the ISI? Of all the thirty or so brigadiers whose postings were announced at that time I was the only one destined for an organization most officers regarded with intense suspicion. if no fear. The ISI was considered all-powerful, and the Director General second only in authority to President Zia, although he was outranked by numerous other generals.

The ISI had responsibility for all intelligence matters at national level. These covered political and military, internal and external security, and counter-intelligence. I knew of its role in outline and its reputation in some detail. The ordinary career officer felt, with justification, that the ISI was watching him personally, that it had its informants reporting on his attitudes and reliability. If an officer was on the ISI staff his peers, and indeed his seniors, tended to shun him socially. I had even noticed this myself in the few hours I spent at Quetta after my posting became known to my comrades on the exercise. I was no longer one of them.

Another reason for my anxiety was having General Akhtar as my immediate superior, not only because of his appointment but because of his daunting reputation. An artillery officer by training, he had fought against India three times, and as a very young officer had witnessed the horrors of mass murder at partition. I believe his hatred of India stemmed from those atrocities at the time of Pakistan’s independence. He had a cold, reserved personality, almost inscrutable, always secretive, with no intimates except his family. Many had found him a hard man to serve due to his brusque manner and his reputation as a disciplinarian. He had many enemies. His success in reaching such high rank had been due to his energy, his boldness and his readiness to drive his command to its limit. I had served under him once before as a battalion commander in his division, so I knew at first hand what a difficult taskmaster he could be. He was totally loyal, totally dedicated to his profession, and, as I was to quickly realize, totally determined to defeat the Soviets. He was later to confide to me that it was his cherished wish to visit Kabul after the war had been won, to offer his prayers of thanks for victory. Although he lived to see the Soviets in retreat, he never got his wish.