Barges and boats were easier, although the high level of activity and security near crossing places meant that these attacks needed to be covert, and therefore during darkness. We required limpet mines that a small recce boat or a swimmer could carry, which could be clamped to the side of the boat just below the water line. For these we turned to the British, via MI-6. They obliged, and it was the UK’s small, but effective, contribution to destroying a number of loaded barges on the Soviet side of the Amu throughout 1986. Others were sunk by recoiless rifle fire from positions in the reeds and swamps near the south bank.

Because the Americans declined to provide maps or photographs of Soviet territory I was hampered in selecting targets both for rocket attacks from inside Afghanistan and for the Mujahideen raiding parties crossing the river. I had to rely on information brought back from operations, such as Wali Beg had provided after his first mission. During 1986 some fifteen Commanders were specially trained in Pakistan for these operations. In particular we concentrated on derailment. A massive amount of freight came down the rail link from Samarkand to Termez, but there was also a link line that hugged the northern bank of the Amu, which was within striking distance. We did succeed with several such attacks, but two large-scale operations failed when the Soviets reacted quickly to cut off the invaders. I am certain they had been forewarned.

Commanders were issued with 107mm Chinese single-barreled rocket launchers (SBRLs) and 122mm Egyptian rocket launchers, with ranges of nine and eleven kilometres respectively, which meant they could set up their firing positions well south of the river, and still bring down effective fire inside the Soviet Union. Teams went across to hit border posts, lay anti-tank and anti-personnel mines on the tracks between posts, and to knock down power lines. Despite the CIA’s advice to the contrary, as they were worried they might fall into Soviet hands, we positioned several Stingers in the north, close to the Amu. On one occasion, in December, 1986, some thirty Mujahideen crossed in rubber boats near the base of the Wakhan panhandle to attack two hydro-electric power stations in Tajikistan. This raid involved an assault on two small Soviet guard posts, during which some eighteen Muslim soldiers surrendered and joined the Jehad. It was later reported that a number were subsequently Shaheed in Afghanistan.

There were many operations launched from the Hazrat Imam district in Kunduz Province, the area from which Wali Beg came. An attractive target that came under rocket attack was the small Soviet town of Pyandzh, set among the cotton fields within a hundred metres of the north bank of the Amu. The attraction was the airfield on the northern edge of the town, which was in frequent use by military planes and helicopters launching retaliatory strikes at villages around Kunduz.

Just to the west of where Wali first crossed the Amu on his goatskin is Sherkhan river port, with its Soviet twin of Nizhniy Pyandzh on the far side (see Map 21). The main road from Kunduz comes north until it almost hits the river at Sherkhan village before swinging west for the 5-kilometre run to the port facilities. It used to be a busy ferry crossing point, but the Soviets built a pontoon bridge to take a road that has two branches leaving Nizhniy

Pyandzh. One goes NE to Dusti, while the other goes NW, before turning back to become the river road that follows the north bank of the Amu all the way to Termez and beyond. The importance of this facility to the Soviets was that the road fed the 201st MRD at Kunduz, and then joined the Salang Highway at their main fuel and vehicle depot Pul-i-Khumri.

I was keen that the Sherkhan/Nizhniy Pyandzh fuel storage complex came under attack. The fuel was stored in tanks and open storage areas on both sides of the river, and there was barrack accommodation for the Soviet border security unit near the northern end of the pontoon bridge. The layout of the area on Map 20 shows it exactly as I was given it by the CIA, with all the territory north of the river blank. I had to pinpoint potential targets and other features from Mujahideen sources, and then try to locate them on the map. The concentric circles were drawn to assist the Commander in estimating the range to his chosen target. Using this map, and the Commanders’ local knowledge, it was not difficult to select a series of alternative firing positions for his rocket launchers. The river, streams, tracks, houses, swamp and road were known to him, and he could point out likely positions and approaches to them on my map. We could then give him the various bearings and ranges from each position to each target. This was important, as few Mujahideen could read a map, but provided we supplied the technical data for firing, they were able to get good results.

In this instance we highlighted the facilities in Nizhniy Pyandzh (the blank area just north of the bridge), emphasizing that so long as the rocket launcher was located within the 7-kilometre circle he would be certain to be in range of the targets in the Soviet Union. The Commander was given complete discretion as to which target he engaged, from which firing position, and when he carried out his attacks. For example, we might ask that he did so once a week for two months, but nothing more specific. Within six weeks of our briefing the Commander at Peshawar, rockets started to rain down on Nizhniy Pyandzh.

These cross-border strikes were at their peak during 1986. Scores of attacks were made across the Amu from Jozjan to Badakshan Provinces. Sometimes Soviet citizens joined in these operations, or came back into Afghanistan to join the Mujahideen. As I have mentioned above, in at least one instance some Soviet soldiers deserted to us. That we were hitting a sore spot was confirmed by the ferocity of the Soviets’ reaction. Virtually every incursion provoked massive aerial bombing and gunship attacks on all villages south of the river in the vicinity of our strike. These were punitive missions, with no other purpose than razing houses, killing people and forcing the survivors to flee, thus creating a belt of ‘scorched earth’ along the Amu, from which it would hopefully prove impossible for the Mujahideen to operate. Their aim was sufficiently to demoralize the population to halt our incursions.

In so far as destroying villages, killing women and children and driving survivors into Pakistani refugee camps were concerned, the Soviets succeeded. But if stopping our attacks or weakening the Mujahideen resolve were their objectives, they failed. We continued to bait the bear until April, 1987, when Soviet diplomatic reaction rather than military, sufficiently frightened Pakistani politicians into ordering us to stop. Perhaps our April attacks were just that much over-ambitious and represented too deep a cut in the Soviet anatomy.

During late 1986 we made tentative plans to continue operations inside the Soviet Union the following spring. With this in mind Commanders were trained, briefed and supplied with the necessary weapons and ammunition before winter set in. In April we hoped to start the offensive with three slightly more ambitious attacks. The first involved a heavy rocket attack on an airfield called Shurob East, some 25 kilometres NW of Termez, near the Soviet village of Gilyambor. It was not a major airfield, but it was in use, and lay only 3 kilometres north of the river, so the firing positions could be in Afghanistan. In early April this bombardment was successfully completed, with the airstrip being engaged several times over a period of ten days.

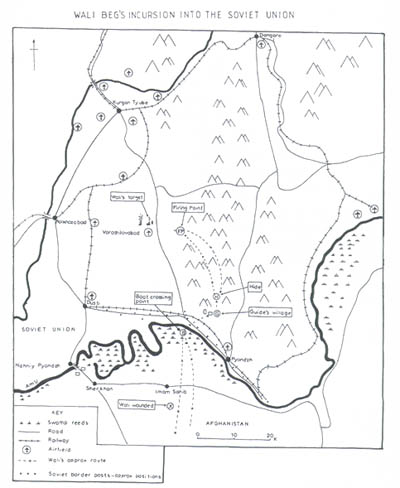

The second attack involved a party of twenty men armed with RPGs and anti-tank mines, tasked with ambushing the frontier road east of Termez, between that town and the Tajikistan border. They were to lay the mines between two security posts, wait for some vehicles to hit the mines, then open fire and withdraw. In the event three soft-skinned Soviet vehicles drove along the road at night, one hit a mine and the two others were destroyed by RPG rounds. Several Soviet soldiers were reported killed or injured, the nearby post opened up with mortar and machine-gun fire, and the Mujahideen pulled back over the Amu. This was followed by the third, and most ambitious, mission which penetrated some 20 kilometres north of the Amu, and struck an industrial target close to the airfield at Voroshilovabad (see Map 21). This was Wali Beg’s operation.