Wali spent two days in the village, much of the time out in the fields as a shepherd with his friends and their sheep. His report was entirely favourable. His contacts would welcome copies of the Holy Koran, and, yes, they would pass them on. Two men had asked for rifles, but Wali had not been able to agree to this at this stage. Perhaps later, if things developed well. weapons would follow, for the moment information on which to plan, and a willingness to provide guides or shelter was all that was needed.

Wali’s two days in the field were most revealing. There was a busy 25-kilometre road running NE between Nizhniy Pyandzh and the town of Dusti. Close to Dusti was an airfield. An overhead electric pylon line followed the road, upon which there was considerable traffic, including many military vehicles. Dusti had a Soviet garrison, and Wali’s friends were certain military planes used the airfield. They told him of a railway line that linked Dusti with the riverside town of Pyandzh some 40 kilometres upriver from where Wali had crossed. This railway had a road paralleling it all the way, and was protected by border posts at regular intervals as it came close to the river for much of its length.

Wali was one of the dozens of Mujahideen who ventured across the river over a period of several months in 1984. Most of them brought back similarly encouraging news. We duly received the Holy Korans and the other books and began to take them over in batches of 100-300 at a time in small rubber boats, or Zodiacs (eight-man wooden recce boats) with small outboard engines. The latter were not popular as they were too noisy. The CIA had provided the boats but could not oblige with the specially silenced outboards that we had requested. About 5,000 Holy Korans were distributed, but the atrocity novels did not have much appeal. I was impressed by the number of reports of people wanting to assist. Some wanted weapons, some wanted to join the Mujahideen in Afghanistan, and others to participate in operations inside the Soviet Union.

We were now in a position to start raising the water temperature.

By 1985 it became obvious that the US had got cold feet. I had asked for more Holy Korans and large-scale maps of the Soviet Union up to 30 kilometres north of the border, on which to plan our incursions, but, while the Holy Korans were no problem, I was told no maps could be provided. It was not that their satellites were not taking the pictures, they were, but somebody at the top in the American administration was getting frightened. From then on we got no information on what was happening north of the Amu from the CIA. They produced detailed maps of anywhere we asked in Afghanistan, but when the sheet covered a part of the Soviet Union, that part was always blank (see Map 20). The CIA, and others, gave us every encouragement unofficially to take the war into the Soviet Union, but they were careful not to provide anything that might be traceable to the US. They quoted some article, which I do not remember, for their sudden inability to help in this respect.

The Afghanistan border with the Soviet Union is over 2,000 kilometres long. For more than half this distance it is the Amu River, but in the west the frontier is merely an erratic line across the desert and barren rocks of southern Turkmenistan to Iran. From my point of view, in selecting suitable Soviet targets, the border divided itself neatly into three. In the east, from Takhar Province to the eastern tip of the Wakhan peninsula where Afghanistan and China briefly touch each other, the border snakes its way through deep mountain gorges. The Wakhan was part of the roof of the world with towering, lofty, icy peaks over 20,000 feet high. Population was sparse, all the valleys cut oft for months on end in the winter, and even in the less inhospitable Badakshan further west there were few worthwhile targets near the border.

Similarly, the western half of the frontier crossed arid land. Only around Kushka (see Map 9), which was the base of supply for the Soviet forces in the extreme west of Afghanistan, were there installations worth attacking.

It was the central 500 kilometres, from Kilif in the west to north of Faizabad in the east, that was the ‘underbelly’ that Casey had described. Throughout 1984 I had expended much time and effort in boosting the Mujahideen activities in the northern provinces. I had persuaded General Akhtar of their importance and managed to increase the allocation of heavier weapons to the more effective Commanders in this area. The problems were largely ones of distance and time. Winter closed our main supply route from Chitral, so much forward planning was necessary to get large convoys to the Mujahideen operational bases facing the Amu. A minor operation would take up to six months to plan and execute, while a major one would need nine. For this reason it was not until 1986 that our campaign started to be effective.

As the optimistic reports came in of contacts anxious to help I had many discussions with my staff as to how we should start bear-baiting in earnest. We decided on a cautious and gradual campaign of incursions, but spread out over a wide area. Depending on our success rate, we could increase the frequency and depth of the penetrations, although I had to assess the Soviet reaction with great care, as I had no wish to provoke a direct confrontation.

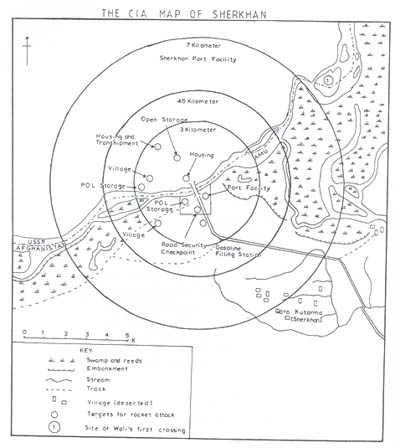

First, there was the river itself. There had always been a brisk trade both along and across the river. Now, with the Amu acting as the forward edge of the Soviet supply base, the traffic across had increased fivefold. All the Soviet freight in trucks and trains headed for the river. The choke points were the crossing places, mainly the bridges at Sherkhan and Hairatan (Termez). This latter was a newly built, l000-metre long iron bridge over the Amu, about 12 kilometres west of Termez. Opened in June, 1982, it had been named the ‘Friendship Bridge’, and was the first road and rail link between the two countries. Built at a cost of 34 million roubles, this bridge was expected greatly to speed up the movement of goods and had greatly strengthened the Soviets’ strategic position. It had enabled the Soviets to establish, for the first time, a railhead on the south side of the Amu. Hairatan was expanded as a port to handle the bulk of the river trade. The bridge marked the start of the Salang Highway on its long journey to Kabul. In addition to the road and rail it also carried the oil pipeline, and as such was second only to the Salang Tunnel as a critical congestion point on the Soviets’ main line of communication.

I started the long process of planning, with the aim of blowing this bridge, in early 1985. I asked the CIA to provide technical advice. They cooperated to the extent of recommending the type and amount of charges needed, where they should be placed, also details of the current, flow and best time of year to destroy it. The expert favoured a summer attack, with a minimum of two spans, preferably three, collapsing. The actual operation would need to be an underwater demolition mission by night. The CIA did not, however, give us good photographs of the bridge; for these we had to rely on the amateur efforts of local Commanders. It was they who also reported on the security arrangements. These consisted of sentries and a company post on the Afghan side, plus an APC on permanent duty. We could identify the guard posts at the Soviet end. I went ahead with ordering all the equipment from the CIA. I called for a Commander to bring a team for special underwater demolition training at a suitable dam inside Afghanistan, but, in late 1985, the operation was called off. General Akhtar had explained what was to happen to the President who had vetoed it immediately. He was worried that its success might trigger a series of sabotage attacks on key bridges inside Pakistan. Personally, I did not consider this likely, but I could not argue. Once again I was thwarted in my efforts to hit the two main Salang Highway bottlenecks—the tunnel and the bridge.