Both Mohammed Khan and Janbaz maintained a following of around 1000 Mujahideen each, which meant our efforts in the area against the real enemy were seriously diminished. Hekmatyar wanted to launch a full-scale attack on Mohammed Khan to drive him out of Pakistan, and we seriously considered using the Pakistan Army to do the same. Both options were equally humiliating. Then came allegations that both Commanders were smuggling drugs into Pakistan to help finance their bases, which was quite likely as Helmand Province is one of the largest poppy-growing regions in Afghanistan.

All our efforts to find an amicable solution failed, primarily because of the covert support Mohammed Khan was receiving from other Parties. It took months before I managed to get this support withdrawn, but by then the damage was done. This feud adversely affected the combat capabilities of Hekmatyar’s Party in the Quetta sector. It never fully recovered.

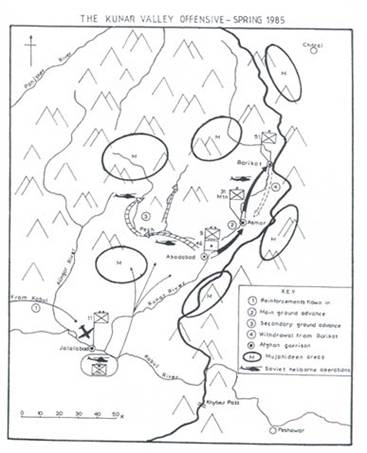

The front line of the eastern provinces was the 100-kilometre Kunar Valley which paralleled the Pakistan border at a distance of 10-12 kilometres (see Map 11). At its base stood Jalalabad, the headquarters of the Soviet 66th MRB and Afghan 11th Division. Half-way up the valley was Asadabad, with the Afghan 9th Division. At the head, almost within rifle range of the frontier, was Barikot with its Afghan garrison of the 51st Brigade. At all the intervening villages the Afghans had constructed defensive posts. Asmar, some 25 kilometres NE of Asadabad, housed the 31st Mountain Brigade and a battalion of Spetsnaz. Such was the importance of the valley to our enemies.

Although there were large numbers of enemy troops deployed in the Kunar Valley, they were, for the most part, bottled up in their forts. The Mujahideen had the perfect sanctuary of Pakistan within a short distance of the valley road and river, and their border bases completely dominated the valley throughout its length. Most Afghan posts were under semi-siege, with the Mujahideen controlling the road, and thus the movement of supplies by truck to maintain the garrisons. All the dominating heights belonged to Pakistan, and we had reason to thank the colonial administrator, Durand, who had so long ago drawn his line with such tactical insight.

Barikot was a typical example of scores of similar Afghan garrisons that fronted the border. Its ground supply line was in the hands of the Mujahideen, it was surrounded by hostile forces, looked down on from every direction, yet it survived. In theory all these forts could be replenished by air if land links were cut, and indeed some were, but the number of such posts, coupled with their isolation in narrow valleys, effectively prevented this type of supply, except for short periods in real emergencies. So how did they feed themselves? The answer lies in yet another of the perversities of the war—they were supplied by local tribesmen from inside Pakistan.

Many Pakistani tribesmen liked to have a foot in both camps. Thousands participated in the Jehad and supported the Mujahideen, but these same people could just as easily give succour to the enemy if there was profit to be had. They found the war provided a variety of additional ways to make money. One of these was the smuggling of food into Afghanistan for sale to the garrisons of border posts. Pulses, flour, cooking oil, rice and items such as petrol, diesel and kerosene for stoves or lamps were purchased by these isolated posts on a regular basis. They came to rely on this source of supply to survive. Even the concrete bunkers at some forts were constructed with cement and iron bars brought direct from Pakistan. On many occasions they bartered arms or ammunition for the goods. There was little we could do to stop it as the Mujahideen supply caravans had to pass through the tribal area, and if the local people were antagonized they would close these routes. The tribes owned transport which was immune from Mujahideen attack, thus rendering them of great value as vehicles to hire to the Afghan Army. With the passage of time, this hiring by the Afghan authorities of tribally-owned buses and lorries became the accepted way of getting some supplies to the more inaccessible posts. These people also did a brisk trade in the sale of arms in Pakistan which they received from KHAD agents, whom they had a habit of harbouring for reasons of financial gain. I would say that these tribes were the people who made the most out of the war, yet they blamed the refugees for ruining their economy.

It was an extraordinary situation in an extraordinary war. On the one hand the Pakistan government was providing full support to the Mujahideen, while on the other thousands of its citizens provided substantial logistic support to its Afghan enemies, enabling them to continue the fight. Militarily, I am convinced that if these Pakistani tribesmen had not sustained our enemy in this way no Afghan post could have endured within 50 kilometres of the frontier.

In January, 1985, we were caught by surprise when the Afghans took to the offensive up the Kunar Valley to relieve Barikot (see Map 11). It was winter, so we had wrongly supposed the Soviets would not take to the field with a major operation, which in turn meant that the Mujahideen bases along the valley, and in the side valleys to the west, were not strongly held. Barikot was still besieged, but with much smaller and less aggressive forces than would have been the case in summer. We had received no warning via satellite.

The enemy task force was under Colonel Gholam Hazrat, the 9th Division commander. He controlled brigades from his own and the Jalalabad-based 11th Division, supplemented by the 46th Artillery Regiment and the 10th Engineer Regiment, whose primary task was road-maintenance and improvement. The Soviet contribution was a single air-assault regiment. The attackers improved on their Panjsher tactics. Armour spearheaded the columns, aerial bombardment flattened the villages to demoralize and disperse the civilian inhabitants, heliborne units seized important heights in advance of the ground thrust, and the same techniques were used up the side valleys such as the Pech. These methods met with success as resistance was thin, a number of small Mujahideen bases were taken, and we could not assemble reinforcements from the refugee camps quickly enough to stop the enemy reaching Barikot.

This offensive was blown up to be a resounding defeat for the Mujahideen Press, radio and television reports publicized the relief of Barikot as proof that the guerrillas were on the run. Colonel Gholam Hazrat was promoted brigadier.

In fact the Afghans had only remained at Barikot for 12 hours. We rushed reinforcements forward to harass the enemy’s lines of communication, particularly around the bases at Asmar and Asadabad. There were several fierce clashes with rearguards, supported by bombers, helicopter gunships and artillery. We kept up the pressure as far as Jalalabad. Nevertheless, I had been disappointed with the Mujahideen’s efforts, and I held a detailed postmortem on what had gone wrong, apart from our being surprised. My enquiries revealed that rivalry and feuding were at least partially to blame. The Kunar Valley between Asmar and Barikot was the responsibility of Commanders belonging to Khalis’ party, and they had not cooperated in resisting this offensive. In particular, Haii Mir Zaman, who had been tasked with road-cratering and mining operations, had failed to perform, giving, with a look of injured innocence, as his excuse that he needed the valley road open to the enemy so that his men could capture rations and weapons to supplement their own stocks which were low. Some of his fellow Commanders dubbed Mir Zaman as a KHAD agent; so I was forced to investigate his activities thoroughly. Although the charges could not be proved, it was clear that such suspicions and accusations did not augur well for coordinated efforts in the Kunar. The whole episode was typical of the difficulties we faced in conducting joint operations, and the amount of time and effort that was wasted trying to sort out Mujahideen feuds rather than devoting our energies to the fighting.