In 1984 we instituted a series of successful attacks on Bagram Air Base during which some twenty aircraft were destroyed on the ground. The story of how one of them was carried out illustrates the system of training and tactics working in practice.

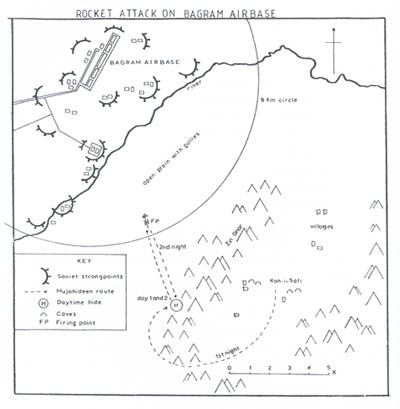

Bagram was a well-protected base with a large garrison (see Map l0). It was primarily a Soviet base, with at least two Fighter Aviation Regiments from the Soviet Union with MiG-21s, MiG-23s, Su-25s and several An-26 transport aircraft. In addition, the Afghan Air Force deployed three fighter squadrons of MiG-21s, plus three fighter-bomber squadrons with Su-7s and Su-22s. The rows of planes parked on the tarmac were tempting targets on which to try out the 107mm Chinese MBRLs that had recently started arriving. Its heavyweight fire (it had twelve barrels) and range of 9 kilometres meant that it could be set up well outside the airfield’s ring of defensive posts, with a good chance of hitting the closely parked planes or other vital facilities. It had been under attack earlier in the year as part of our efforts to distract the Soviets from their seventh Panjsher offensive, but this would be the first time we were able to mount long-range stand-off attacks.

Our operational conference agreed that Bagram merited sustained pressure and that Commanders should be selected and trained accordingly. Among the various Party Leaders and officials, I spoke to the Military Committee representative of Nabi’s Party, who maintained a Mujahideen base some 15 kilometres to the SE of Bagram, near Koh-i-Safi. Between us we agreed on a suitable Commander who should bring thirty men with him for training. A messenger was despatched to Koh-i-Safi. There was then a wait of about five weeks, which was the time required for the messenger to reach his destination, the Commander to collect his men and for them all to arrive at Peshawar. I was then informed and would normally send my operations staff officer to conduct the preliminary interview and assessment.

My officer wanted to find out as much as possible about the man and his following. The Commander was photographed, he was queried on his Party affiliation, the exact location of his base, the extent of the area in which he operated, the strength of his force, details of the heavy weapons already issued, any previous training, and recent operations. Also, we wanted information on the other Commanders within a 50-kilometre radius of his base, and we asked if he was willing to cooperate with them. We built up a pen picture of the man, with an assessment of his potential. In this case we discussed his likely objective —Bagram—and received a favourable response. As the years passed we built up a library of information on individuals, and in most cases knew far more about the Commanders than their Party Leaders.

This particular commander had up to 400 men at his disposal, based around Koh-i-Safi where maximum use had been made of the numerous caves in the area to provide concealment and shelter from bombing. The base was screened from Bagram by a steep-sided ridge that rose in places to almost 6,000 feet. In this instance the Commander had followed instructions and only brought thirty men. So often they sought to impress us by bringing twice the number, causing grave problems as we could not train them all. On the specified night the Mujahideen were assembled at a RV at Peshawar where they boarded closed trucks to take them to the training camp. On arrival they had no idea where they were. They would remain for the 2-3 week course, before being driven out back to Peshawar in the same manner.

The thirty Mujahideen received intensive training on the handling and firing of the MBRL. The course was entirely practical, starting with assembling and disassembling, preparation of the rockets, estimated ranges, setting the bearing and elevation, loading and firing. They learnt that the MBRL was heavy, its main disadvantage, as it took three men to manpack its three components (wheels, stand and barrels) and this was only practical for short distances. For the Bagram operation mules would be necessary. They learned to make up gun teams of three, one aiming and setting, two loading, cranking (it was fired by a crank handle), and firing (by pressing a button). Although it had twelve barrels the rockets were fired singly, not in one broadside. They had to learn to spot the fall of shot and estimate whether it had gone too far, left or right, or short of the target. For this they use binoculars, they had to shout corrections—‘drop 100’, ‘up 300’, or ‘left 200’ to the crew, so that adjustments could be made. They were becoming artillerymen.

They were also taught to improvise. The rockets could be fired electrically, using a makeshift bipod or support. In the field this usually meant propping them up on a pile of rocks, although against pinpoint targets the chances of a hit were small, but this method could be used against a barracks, airfield or fuel storage depot, for example.

While his men mastered the weapon itself, the Commander spent a lot of time with his training officer discussing tactics. The commander had to know the characteristics of the MBRL, how to divide his men into crews and the OP party, how best to site both so that they were concealed, with the MBRL in dead ground. He was taught that his tactics would normally be to move into a firing position in the dark, fire in the dark and withdraw under cover of darkness to a previously selected hide, if time did not permit a clean break before dawn. This procedure largely negated the Soviet control of the air. Not only were they reluctant to fly at night, but if they did so using flares their firing was always haphazard. The only problem was the near impossibility of spotting the fall of shot, particularly from level ground. Sometimes it was possible to fire a few rockets at night, use the following day to discover whether the target had been hit and, if not, make the adjustments and fire again the next night. Pinpoint accuracy was not so essential with area targets such as Bagram airfield.

Commanders were often surprised at the logistic and transport effort required to move these weapons and their ammunition. The MBRL, with its wheels and stand, could be carried by three mules, with another mule for every four rockets. For a mission involving firing thirty-six rockets (not an excessive number) from one MBRL, simple arithmetic told him he would need twelve mules. With crew, OP party, protection party and mule handlers, just to get one MBRL into action would require twenty to twenty-five men.

On this occasion my training officer and the Commander spent many hours pouring over aerial photographs and maps of the Bagram area looking for likely firing points and good approaches to them. Map 10 makes clear the tactical problems. Koh-i-Safi is 15 kilometres in a straight line from the Bagram runway, with the precipitous Zin Ghar ridge, which dominates the Bagram plain, only 2 kilometres to the NW. Although it gave excellent observation over a huge sweep of country up to the airfield itself, it could only be crossed, using mules, by one or two circuitous and steep footpaths to the west of Koh-i-Safi. The Commander was insistent that he knew thisroute well, and that the alternative, shorter route around the northern tip of the ridge would mean moving through a more populous area.

They had to get the MBRL to within 9 kilometres of the airfield, so a circle was drawn on the map, much as on Map 10. The firing point had to be inside this circle. Often circles with a 7 5 and 3 kilometre radius were also drawn. The object was to select two or three likely firing-point positions, measure distances and bearings to the target and record this information for the Commander. To my officer neither the photographs or the map suggested any satisfactory positions. The track from the Zin Ghar ridge led into the southern portion of the open Bagram plain, which seemed devoid of cover and sloped gently NW towards the airfield and the Soviet outposts. It was also cries-crossed with a confusion of paths and tracks making night-time navigation problematic. More importantly, the flatness and lack of cover over the area posed a serious security dilemma. Dawn or dusk would be likely to catch the maximum number of aircraft on the ground. If, however, the attack was launched just before first light there was the problem of getting away in daylight. A daytime hide would be needed to allow a full night for the final approach, firing and withdrawal. My officer pointed out that once Bagram came under fire it would be like kicking open a hornets’ nest. The Soviets would respond with artillery and helicopter. gunships within a matter of minutes. If they did so in daylight the chances of the Mujahideen reaching the cover of Zin Ghar, some six kilometres away, unscathed were remote. Better to take the risk of discovery in their hide by day by some wandering herdsman or traveller. The Commander agreed.