A secure base of supply in which you can stockpile all the necessary weapons of war is useless unless the items can be delivered to the units in the field. For that lines of communication are essential. They are the arteries and veins of an army. Just as a human heart pumps blood along these veins to all parts of the body, so a strategic base must pump supplies to all parts of an army. Block a minor road for a short period and a unit is inconvenienced until the route is cleared, just as a cut finger will bleed until bandaged. Neither are serious injuries. But sever or block an army’s main line of communication and it must be retaken or the army will die, just as surely as a patient with a severed artery will die without immediate attention.

Map 6 indicates the Soviets’ ground logistics system. They were able to airlift supplies to most of their garrisons or operational bases if necessary, and they did so, particularly in emergencies when a post was surrounded. But air supply could not replace ground lines of communication, the scale of their needs was so immense. If the Termez base of supply was their heart, then Kabul was the head of the Soviet forces inside Afghanistan. Here was their forward headquarters, here was the centre of the communist government, and whoever sat at the centre controlled the country, at least as far as the outside world was concerned. The artery, the main line of communication, that kept Kabul functioning was Highway 2, the Salang Highway. It stretched for 450 vulnerable kilometres. It had been, and was to continue to be, the scene of some of the most successful Mujahideen ambushes of the war.

From Kabul other routes led forward to the limbs of the Soviet forces. Highway 1 led south to Ghazni, and then to Kandahar 500 kilometres away to the SW. Route 157 went due south to the garrison at Gardez 120 kilometres away, and the eastern arm of Highway l led to Jalalabad, and thence to Peshawar via the Khyber Pass. Each of these roads was important. If they were cut it was painful, and possibly incapacitating for a while, but it was not fatal.

In the west the secondary base around Kushka fed the forces at Herat and Shindand. In comparison to the east and the north this was a backwater of the war. Its importance lay in acting as a buffer against Iran. To get from Shindand to Kabul, by the southern route, necessitated taking the great ‘ring road’ via Kandahar. One thousand kilometres of tortuous, back-breaking, blistering motoring, every one through hostile provinces, and much of it across the Desert of Death.

The more I examined the map the more I understood the Soviet’s problems. Their main lifeline, the Salang Highway, and its extension for 500 kilometres further south to Kandahar, was comparatively close to and, most importantly, parallel to, the Pakistan border. The Mujahideen’s main base, with all its jump-off points, was within striking distance of the Soviets’ principal north-south line of communication for over a distance of 1000 kilometres. The Parachinar (Parrot’s Beak) peninsula pointed directly at Kabul. From its tip the centre of communist Afghanistan was only 90 kilometres away. By a strange coincidence a similar peninsula, also, called the Parrot’s Beak, had jutted out from Cambodian territory only 65 kilometres from Saigon in South Vietnam. This gave us a great strategic advantage. Not only did the Soviets depend on one single highway in the critical eastern portion of the country, but it was excessively long, passed through Mujahideen-held areas and across the Hindu Kush mountains, but it was exposed throughout its length to the enemy frontier ( Pakistan ). We, on the other hand, had many routes into Afghanistan from the border bases, and they were comparatively short to the eastern provinces, and certainly far less exposed to attack.

As I well knew, the longer an army’s line of communication the weaker the forces in the field. This is because such an army must deploy a high proportion of its troops protecting supply lines. The longer the route the more guards required, and the weaker the field force. This was the case with the Soviet and Afghan Armies. It was a major factor in limiting their ability to gather together a sizeable force for prolonged operations in the rural areas. I would estimate that 9 out of 10 of the enemy soldiers were committed to static defensive duties, garrisoning posts protecting roads or logistic bases, convoy escorts and administrative tasks.

The Soviets were sensitive to threats against their main supply line because they really only had one in the part of the country that mattered. They could not switch to another line if the Salang Highway was blocked. It was also their line of retreat. Eventually, when in 1988/89 the Soviets withdrew, it was up this road. In terms of military strategy theirs was an awkward position. Their forces had been compelled, by the relative positions of their supply base and Pakistan, to ‘turn front to flank’. In other words their army had marched south for several hundred kilometres to the Kabul area with their supply route trailing behind them. Then, to get to the critical eastern provinces and face the enemy frontier, they had to turn left (east). Their front was now facing towards what had been their flank, but their line of communication was still running north-south, and so much more exposed to attack. The Mujahideen did not have this problem.

Despite these advantages, I had to be careful to remember that the Mujahideen were a guerrilla force and could not, in 1983, confront their opponents in a conventional stand-up battle. Our strategy must remain one of a thousand cuts. There is a great deal of difference between a stroke that cuts a major supply route and keeps it severed and a raid that is a fleeting attack which causes losses but does not block the route for a long period. To achieve the former on the Salang Highway would require a substantial force, able and prepared to hold on to the blocking position in the face of the inevitable massive air and ground counter-attack. Such a strategy was, I believed, beyond the capacity of the Mujahideen even had I been able to get sufficient concentration and cooperation The better strategy would be the raid, the ambush, the stand-off attack but made with such frequency and ferocity that the loss of blood from these multiple cuts would seriously weaken the enemy’s ability to continue. Such pressure on the supply lines would have the added benefit of compelling the Soviets to tie down an ever higher proportion of their men in static security duties. The initiative would be retained by the Mujahideen with all that would mean in terms of their morale, and in convincing their backers to keep supporting them.

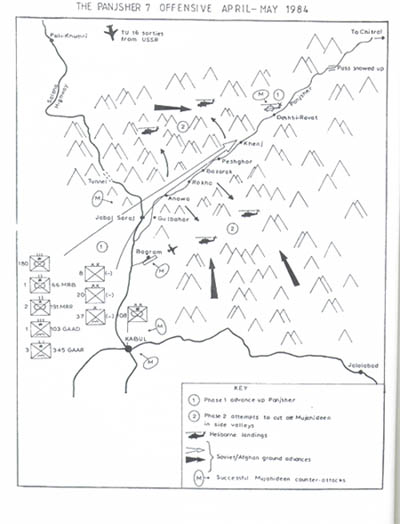

During my early weeks I met with General Akhtar several times to discuss an overall strategy for the war. In his view 1984 would see the Soviets continue to adopt their generally defensive posture, with emphasis on protecting important political centres, lines of communication and key installations, such as airfields, dams, industrial sites and hydro-electric plants. He foresaw the enemy confining any major operations to those necessary to increase security to the above vulnerable points. These would be likely in areas close to the Pakistan border to disrupt the Mujahideen supply routes, and in Mujahideen operational base areas close to important cities or air bases such as Kabul and Bagram. The Panjsher valley (see Map 7), which had so often been the springboard for attacks on the Salang Highway, and which had already been the target for no less than six major sweep operations in the first three years of the war, was considered the likely location of another Soviet offensive.

Akhtar also anticipated a build-up of air and artillery violations across the border into Pakistan. He saw the desire to create a widening rift between the local Pakistani population and the refugees as a crucial part of Soviet strategy. Sabotage and subversion would continue to be used to destabilize Pakistan, and this would include the provision of arms and money to tribes in the frontier areas that had always been hostile to the central government at Islamabad. If a breakdown of law and order could be fomented then it would put further pressure on Pakistan, which at this time meant President Zia, to withdraw its support for the Jehad. We both agreed that the Soviets seemed wedded to a military defensive strategy in Afghanistan, aimed at holding what they had got, coupled with a sabotage offensive in Pakistan, aimed at making support for the Mujahideen too expensive politically for Zia. The Soviets seemed disinclined to raise the stakes with large-scale reinforcements, hoping that in the long run the inability of the Mujahideen to capture key towns and the progressive destruction of the villages and rural infrastructure would make them give up the struggle through sheer war-weariness.