I mention this now because Wilson epitomized the attitude of many American officials that I met that Afghanistan must be made into a Soviet Vietnam. The Soviets had kept the Viet-Cong supplied with the hardware to fight and kill Americans, so the US would now do the same for the Mujahideen so they could kill Soviets. This view was similarly prevalent among CIA officers including, particularly, the Director, William Casey. I could see they were deeply resentful of their failure to win in Vietnam, which had been a major military defeat for the world’s leading superpower. To me, getting their own back seemed to be the primary reason for the US backing the war with so much money. I have no doubt that the State Department had many valid strategic and political reasons for US support. hut I am merely emphasizing that many American officials appeared to regard it as a God-given opportunity to kill Soviets, without any US lives being endangered. General Akhtar agreed with them that the war could be turned into a Soviet Vietnam. He had convinced the President it was entirely feasible, and now it was my job to see it carried out.

Certainly it seemed there were numerous similarities between the two wars. At the political level both involved superpowers fighting in a foreign country on the Asian continent; in both cases they fought to prop up a government that was corrupt and unpopular with the majority of the population; in both Vietnam and Afghanistan huge, modern, conventional forces fought, at least initially, a guerrilla force; and in troth instances the superpower fatally underestimated their enemy, considering. at the outset, speedy victory within their grasp.

Strategically the terrain favoured the guerrillas in both countries with the jungle-covered mountains of Vietnam, and the high, barren, rocky mountains of Afghanistan providing refuge and cover from the air to the insurgents. Both the US and Soviet Union relied heavily on airpower to compensate for their inability to meet their enemies on equal terms on the ground. For the conventional armies it was primarily a defensive war on land, with each trying to retain control over cities, communication centres, towns and strategic military bases, leaving the rural areas to the guerrillas. Both wars saw the use of terror and the indiscriminate bombing of villages which were supposedly sheltering the enemy. The guerrillas in Vietnam could obtain reinforcements, supplies and sanctuary across the borders in Laos and Cambodia, while the Mujahideen sought the same in Pakistan.

At the tactical level the superpowers depended heavily on firepower, rather than infantry manpower, to destroy their elusive opponents. Both re-learned the lesson that this tactic on its own does not defeat the guerrilla.

The Americans coined a new military phrase, search and destroy, which became synonymous with surrounding a village or locality, then pounding it from the air and ground, irrespective of who was inside the cordon. Afterwards, there was a body count and the units claimed another victory. The Soviets copied this type of haphazard slaughter with great zeal, although they were not so adept at the cordoning. Neither America nor the Soviet Union could have survived as long as they did without the helicopter; but even then this wonder weapon could not give either the victory they sought. The attitudes of the soldiery of both superpowers developed along remarkably similar lines. Both were largely conscript armies, whose men fought with great reluctance—in order to survive. They had no interest in the war, no cause with which they could relate. This resulted in poor performance, particularly at small-unit level. Morale dropped alarmingly, and many resorted to alcohol or drugs in order to forget. With the Americans it led to widespread ‘combat refusals’, and over a thousand cases of fragging (soldiers murdering their own officers). With certain notable exceptions, the average US and Soviet infantryman proved, at best mediocre, at worst useless. It was the inevitable result of their governments expecting reluctant conscript troops to fight in a war in which they could see no purpose.

Interestingly, the career officers of both armies saw the war differently from their men. It was, for them, an opportunity to further their careers. Many did this, ‘punching their ticket’ with (for the Americans) a six-month tour to gain combat experience. Something like 60,000 Soviet officers went through the Afghanistan war, thus qualifying for the ‘Afghan Brotherhood’, membership of which was so often rewarded with promotion and medals.

I was now cast in the role of overall guerrilla leader. I ran over in my mind the recognized criteria normally necessary for an armed resistance movement to succeed: first, a loyal people who would support the effort at great risk to themselves, a local population, the majority of whom would supply shelter, food, recruits and information. The Afghan people in the thousands of rural villages met this requirement. Second, the need for the guerrilla to believe implicitly in his cause, for him to be willing to sacrifice himself completely to achieve victory. The Afghans had Islam. They fought a Jehad, they fought to protect their homes and families. Third, favourable terrain. With over two-thirds of Afghanistan covered by inhospitable mountains known only to the local people, I had no doubts about this. Fourth, a safe haven—a secure base area to which the guerrilla could withdraw to refit and rest without fear of attack. Pakistan provided the Mujahideen with such a sanctuary. Fifth, and possibly most important of all, a resistance movement needs outside backers, who will not only represent his cause in international councils, but are a bountiful source of funds. The US and Saudi Arabia certainly fulfilled this role. General Akhtar had been right; the ingredients for military victory were all there. I needed to give careful thought to where, and how, to apply the thousand cuts to bring down the bear.

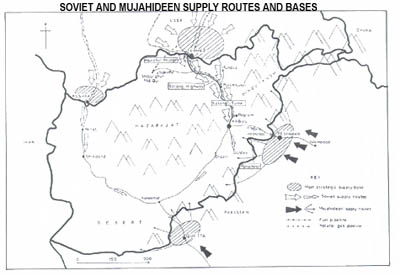

It was important for me to understand the military geography of Afghanistan and how it related to the bases and lines of communication of both sides (see Map 6). No army, not even a guerrilla one, can fight a prolonged campaign without bases with lines of communication leading from them to the troops in the field. There are two types of base—the main strategic base of supply and the operational bases. The main bases of supply in this case were the Soviet Republics of southern Central Asia, from the borders of Iran in the west to China in the east, and for the Mujahideen the western border areas of Pakistan. Behind these frontiers were the depots, stores, training camps, main ammunition dumps, staging areas and, in the case of the Soviets, airfields that supplied the forces in Afghanistan. In both cases they had so far been immune from serious attack. Units could return for resting and refitting, and reinforcements could assemble unhindered. These were extremely long frontiers, each stretching several thousand kilometres. The Pakistan—Afghanistan border was mountainous for 90 per cent of its length, and in western Baluchistan there was desert. This frontier followed bleak and formidable barriers. Because of the excessive length of both borders, these bases of supply were developed around two towns in each country. In the Soviet Union Termez saw 75 per cent of supplies destined for Afghanistan pass through it, while the remainder went via Kushka. For the Mujahideen, Peshawar was the centre of their supply organization, with Quetta the secondary one in the south.

Operational bases were different. They were tactical bases inside Afghanistan, upon which formations or units were dependent for their immediate battlefield needs on a day-to-day basis. They were also usually the locations at which the units were stationed, and from which they sallied out on operations. After a sweep operation the Soviets would normally withdraw to their operational base; similarly, the Mujahideen would retire to their local base area after an ambush or rocket attack. For the Soviets the main operational bases were the larger cities and airfields such as Kabul, Bagram, Kunduz, Jalalabad, Shindand, Kandahar, and the newly built depot just south of Pul-i-Khumri. The Mujahideen used the hundreds of small villages and valleys scattered all over Afghanistan. Every Commander had his operational base.