Lewis had been talking whilst these and similar thoughts were crossing and recrossing Morse's mind, and he hadn't heard a word of what was said.

'Pardon, Lewis?'

'I just say that's what we used to do, that's all – over the top of the head, as I say, and put the date against it.'

Morse, unable to construe such manifest gobbledegook, nodded as if with full understanding, and led the way to the car. A large white-painted graffito caught his eye, sprayed along the lower wall of a house in the next terrace: HANDS OFF CHILE – although it was difficult to know who in this benighted locality was being exhorted to such activity – or, rather, inactivity. TRY GEO. LUMLEY's TEA 1s 2d, seemed a more pertinent notice, painted over the bricked-up first-floor window of the next corner house, the lettering originally worked in a blue paint over a yellow-ochre background, the latter now a faded battleship-grey; a notice (so old was it) that Joanna might well have seen it every day as she walked along this street to school, or play – a notice from the past which a demolition gang of hard-topped men would soon obliterate from the local-history records when they swung their giant skittle-balls and sent the side-wall crumbling in a shower of dust.

Just like the Oxford-City-Council Vandals when…

Forget it, Morse!

'Where to now, sir?'

It took a bit of saying, but he said it: 'Straight home, I think. Unless there's something else you want to see?'

Chapter Thirty-nine

And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is

fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment

(T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding)

Morse seldom engaged in any conversation in a car, and he was predictably silent as Lewis drove the few miles out towards the motorway. In its wonted manner, too, his brain was meshed into its complex mechanisms, where he was increasingly conscious of that one little irritant. It had always bothered him not to know, not to have heard – even the smallest things:

'What was it you were saying back there?'

'You mean when you weren't listening?'

'Just tell me, Lewis!'

'It was just when we were children, that's all. We used to measure how tall we were getting. Mum always used to do it – every birthday – against the kitchen wall. I suppose that's what reminded me, really – looking in that kitchen. Not in the front room – that was the best wallpaper there; and, as I say, she used to put a ruler over the top of our heads, you know, and then put a line and a date… '

Again, Morse was not listening.

'Lewis! Turn round and go back!'

Lewis looked across at Morse with some puzzlement.

'I said just turn round,' continued Morse – quietly, for the moment. 'Gentle as you like – when you get the chance, Lewis – no need to imperil the pedestrians or the local pets. But just turn round?

Morse's finger on the kitchen switch produced only an empty 'click', in spite of what looked like a recent bulb in the fixture that hung, shadeless, from the disintegrating plaster-boards. The yellowish, and further yellowing, paper had been peeled away from several sections of the wall in irregular gashes, and in the damp top-corner above the sink it hung away in a great flap.

'Whereabouts did you use to measure things, Lewis?'

' 'Bout here, sir.' Lewis stood against the inner door of the kitchen, his back to the wall, where he placed his left palm horizontally across the top of his head, before turning round and assessing the point at which his fingertips had marked the height.

'Five-eleven, that is – unless I've shrunk a bit.'

The wallpaper at this point was grubby with a myriad fingerprints, appearing not to have been renovated for half a century or more; and around the non-functioning light-switch the plaster had been knocked out, exposing some of the bricks in the partition-wall. Morse tore a strip from the yellow paper, to reveal a surprisingly well-preserved, light-blue paper beneath. But marked memorials to Joanna, there were none; and the two men stood silent and still there, as the afternoon seemed to grow perceptibly colder and darker by the minute.

'It was a thought, though, wasn't it?' asked Morse.

'Good thought, sir!'

'Well, one thing's certain! We are not going to stand here all afternoon in the gathering gloom and strip all these walls of generations of wallpaper.'

'Wouldn't take all that long, would it?'

'What? All this bloody stuff-'

'We'd know where to look.'

'We would?'

'I mean, it's only a little house; and if we just looked along at some point, say, between four feet and five feet from the floor – downstairs only, I should think-'

'You're a genius – did you know that?'

'And you've got a good torch in the car.'

'No,' admitted Morse. I’m afraid-'

'Never mind, sir! We've got about half an hour before it gets too dark.'

It was twenty minutes to four when Lewis emitted a child-like squeak of excitement from the narrow hallway. 'Something here, sir! And I think, I think-' 'Careful! Careful' muttered Morse, coming nervously alongside, a triumphant look now blazing in his blue-grey eyes.

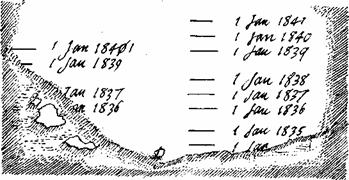

Gradually the paper was pulled away as the last streaks of that December day filtered through the filthy skylight above the heads of Morse and Lewis, each of them looking occasionally at the other with wholly disproportionate excitement. For there, inscribed on the original plaster of the wall, below three layers of subsequent papering – and still clearly visible – were two sets of black-pencilled lines: the one to the right marking a series of eight calibrations, from about 3' 6" of the lowest one to about 5' of the top, with a full date shown for each; the one to the left with only two calibrations (though with four dates) – a diagonal of crumbled plaster quite definitely precluding further evidence below.

For several moments Morse stood there in the darkened hallway and gazed upon the wall as if upon some holy relic.

'Get a torch, Lewis! And a tape-measure!'

'Where-?'

'Anywhere. Everybody's got a torch, man.'

'Except you, sir!'

'Tell 'em you're from the Gas Board and there's a leak in Number 12.'

‘The house isn't on gas.'

'Get on with it, Lewis!'

When Lewis returned, Morse was still considering his wall-marks – beaming as happily at the eight lines on the right as a pools-punter surveying a winning-line of score-draws on the Treble Chance; and, taking the torch, he played it joyously over the evidence. The new light (as it were) upon the situation quickly confirmed that any writing below the present extent of their findings was irredeemably lost; it also showed a letter in between the two sets of measurements, slightly towards the right, and therefore probably belonging with the second set.

The letter 'D'!

Daniel!

The lines on the right must mark the heights of Daniel Carrick; and, if that were so, then those to the left were those of Joanna Franksl

'Are you thinking what I'm thinking, Lewis?'

'I reckon so, sir.'

'Joanna married in 1841 or 1842' – Morse was talking to himself as much as to Lewis – 'and that fits well because the measurements end in 1841, finishing at the same height as she was in 1840. And her younger brother, Daniel, was gradually catching her up – about the same height in 1836, and quite a few inches taller in 1841.'