'- and I thought of "Hefty" Donavan. F. T. Donavan. And I'll put my next month's salary on that "F" standing for "Frank"! Huh! Who's ever heard of a wife calling her husband by his surname?'

'I have, sir.'

'Nonsense! Not these days.'

'But it's not these days. It was-'

'She was calling Frank Donavan – believe me!'

'But she could have been queer in the head, and if so-'

'Nonsense!'

'Well, we shan't ever know for sure, shall we, sir?'

'Nonsense!'

Morse sat back with the self-satisfied, authoritative of a man who believes that what he has called 'nonsense three times must, by the laws of the universe, be necessarily untrue. 'If only we knew how tall they were – Joanna and… and whoever the other woman was. But then is just a chance, isn't there? That cemetery, Lewis-'

'Which do you want first, sir? The good news or the bad news?'

Morse frowned at him. 'That's…?' pointing to the envelope.

'That's the good news.'

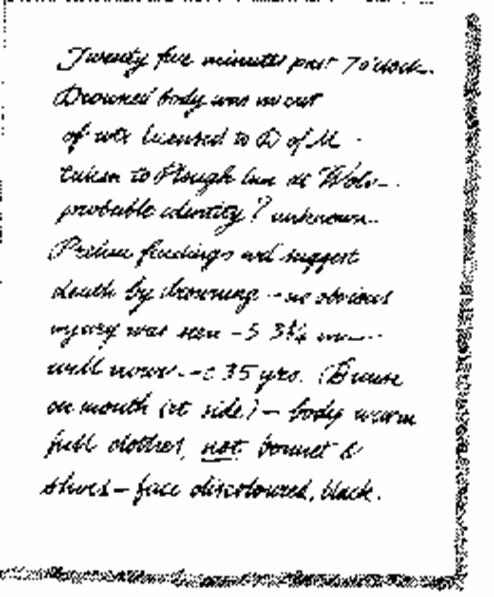

Morse slowly withdrew and studied the photocopied sheet.

‘Not the Coroner's Report, sir, but the next best thing.

‘This fellow must have seen her before the post-mortem. Interesting, isn't it?'

‘Very interesting.'

The report was set out on an unruled sheet of paper, dated, and subscribed by what appeared as a 'Dr Willis', for writing was not only fairly typical of the semi-legibility forever associated with the medical profession, but was also beset by a confusion with 'm's, 'w's, 'n's, and 'u's – all these letters appearing to be incised with a series of what looked like semi-circular fish-hooks. Clearly the notes of an orderly-minded local doctor called upon to certify death and to take the necessary action – in this case, almost certainly, to pass the whole business over to some higher authority. Yet there were one or two real nuggets of gold here: the good Willis had made an exact measurement of height, and had written one or two most pertinent (and, apparently, correct) observations. Sad, however, from Morse's point of view, was the unequivocal assertion made here that the body was still warm. It must have been this document which had been incorporated into the subsequent post-mortem findings, thenceforth duly reiterated both in Court and in the Colonel's history. And it was a pity; for if Morse had been correct in believing that another body had been substituted for that of Joanna Franks, that woman must surely have been killed in the early hours of the morning, and could not therefore have been drowned some three or four hours later. Far too risky. It was odd, certainly, that the dead woman's face had turned black so very quickly; but there was no escaping the plain fact that the first medical man who had examined the corpse had found it still warm.

Is that what the report had said, though – 'still warm'? No! No, it hadn't! It just said 'warm'… Or did it?

Carefully Morse looked again at the report – and sensed the old familiar tingling around his shoulders. Could it be? Had everyone else read the report wrongly? In every case the various notes were separated from each other by some form of punctuation – either dashes (eight of them) or full stops (four) or question-marks (only one). All the notes except one, that is: the exception being that 'body warm / full clothes… ' etc. There was neither a dash nor a stop between these two, clearly disparate, items – unless the photocopier had borne unfaithful witness. No! The solution was far simpler. There had been no break requiring any punctuation! Morse looked again at line 10 of the report,

and considered three further facts. Throughout, the 's's were written almost as straight vertical lines; of the fifteen or so 'i' dots, no fewer than six had remained un-dotted; and on this showing Willis seemed particularly fond of the word 'was'. So the line should perhaps – should certainly! – read as follows: 'on mouth (rt side) – body was in'. The body 'was in full clothes'! The body was not 'warm'; not] in Morse's book. There, suddenly, the body was very, very cold.

Lewis, whilst fully accepting the probability of the alternative reading, did not appear to share the excitement which was now visibly affecting Morse; and it was time for the bad news.

'No chance of checking this out in the old Summertown graveyard, sir.'

'Why not? The gravestones are still there, some of them – it says so, doesn't it? – and I've seen them myself – '

'They were all removed, when they built the flats there.'

'Even those the Colonel mentioned?'

Lewis nodded.

Morse knew full well, of course, that any chance of getting an exhumation order to dig up a corner of the greenery in a retirement-home garden was extremely remote. Yet the thought that he might have clinched his theory… It was not a matter of supreme moment, though, he knew that; it wasn't even important in putting to rights a past and grievous injustice. It was of no great matter to anyone – except to himself. Ever since he had first come into contact with problems, from his early schooldays inwards – with the meanings of words, with algebra, with detective stories, with cryptic clues – he had always been desperately anxious to know the answers, whether those answers were wholly satisfactory or whether they were not. And now, whatever had been the motive leading to that far-off murder, he found himself irked in the extreme to realize that the woman – or a woman – he sought had until so very recently been lying in a marked grave in North Oxford. Had she been Joanna Franks, after all? No chance of knowing now – not for certain. But if the meticulous Dr Willis had been correct in his measurements, she couldn't have been Joanna, surely?

After Lewis had gone, Morse made a phone call.

'What was the average height of women in the nineteenth century?'

'Which end of the nineteenth century, Morse?'

'Let's say the middle.'

'Interesting question!'

'Well?'

'It varied, I suppose.'

'Come on!'

'Poor food, lack of protein – all that sort of stuff. Not very big, most of 'em. Certainly no bigger than the Ripper's victims in the 1880s: four foot nine, four foot ten, four foot eleven – that sort of height: well, that's about what those dear ladies were. Except one. Stride, wasn't her name? Yes, Liz Stride. They called her "Long Liz" – so much taller than all the other women in the work-houses. You follow that, Morse?'

'How tall was she – "Long Liz"?'

'Dunno.'

'Can you find out?'

'What, now?'

'And ring me back?'

'Bloody hell!'

Thanks.'

Morse was three minutes into the love duet from Act One of Die Walkiire when the phone rang.

'Morse? Five foot three.'

Morse whistled.

'Pardon?'

'Thanks, Max! By the way, are you at the lab all day tomorrow? Something I want to bring to show you.'

So the 'petite' little figure had measured three quarters of an inch more than 'Long Liz' Stride! And her shoes as Lewis had ascertained, were about size 5! Well, well, well! Virtually every fact now being unearthed (though that was probably not le mot juste) was bolstering Morse's bold hypothesis. But, infuriatingly, there was, as it seemed, no chance whatever of establishing the truth. Not, at any rate, the truth regarding Joanna Franks.