One day Fernando López Tapia told me he had to talk to me. When I went in to see him he said that he wanted us to live together. I thought he was kidding, because sometimes Fernando gets in these moods, wanting to live with everybody in the world, and I assumed we'd probably go to a hotel that night and make love and he would get over wanting to set me up in an apartment. But this time he was serious. Of course, he had no intention of leaving his wife, at least not all of a sudden, but gradually, in a series of done deeds, as he put it. For days we talked about the possibility. Or rather, Fernando talked to me, laying out the pros and cons, and I listened and thought carefully. When I told him no, he seemed crushed, and for a few days he was angry at me. By then I had started to send my pieces to other magazines. Most places turned them down, but a few accepted them. Things got worse with Fernando, I'm not sure why. He criticized everything I did and when we slept together he was even rough with me. Other times he would be sweet, giving me presents and crying at the least little thing, and by the end of the night he'd be dead drunk.

Seeing my name published in other magazines was a great thing. It gave me a feeling of security and I began to distance myself from Fernando López Tapia and Tamal. At first it wasn't easy, but I was already used to hardships and they didn't faze me. Then I found work as a copy editor at a newspaper and I quit Gigante. We celebrated my last day with a dinner attended by Jacinto, María, Franz, and me. That night, while we were eating, Fernando López Tapia came to see me but I wouldn't let him in. He was shouting in the street for a while and then he left. Franz and Jacinto watched him from the window and laughed. They're so alike. María and I didn't want to look and we pretended (though maybe we weren't quite pretending) to be in hysterics. What we were really doing was staring into each other's eyes and saying everything we had to say without speaking a word.

I remember that we had the lights off and that Fernando's shouts drifted up muffled from outside, they were desperate shouts, and that then we didn't hear anything, he's leaving, said Franz, they're taking him away, and that then María and I looked at each other, not pretending anymore but serious, tired but ready to go on, and that after a few seconds I got up and turned on the light.

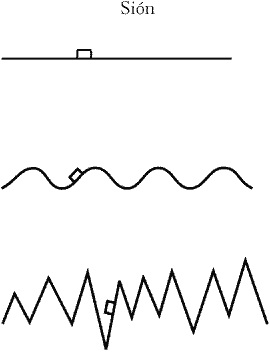

Amadeo Salvatierra, Calle República de Venezuela, near the Palacio de la Inquisición, Mexico City DF, January 1976. And then one of the boys asked me: where are Cesárea Tinajero's poems? and I emerged from the swamp of mi general Diego Carvajal's death or the boiling soup of his memory, an inedible, mysterious soup that's poised above our fates, it seems to me, like Damocles' sword or an advertisement for tequila, and I said: on the last page, boys. And I looked at their fresh, attentive faces and I watched their hands turn those old pages and then I peered into their faces again and they looked at me too and they said: we aren't losing you, are we, Amadeo? do you feel all right, Amadeo? do you want us to make you some coffee, Amadeo? and I thought oh, hell, I must be drunker than I thought, and I got up and walked unsteadily over to the front room mirror and looked myself in the face. I was still myself. Not the self I'd gotten used to, for better or for worse, but myself. And then I said, boys, what I need isn't coffee but a little more tequila, and when they'd brought me my cup and filled it and I'd drunk, I could separate myself from the confounded quicksilver of the mirror I was leaning against, or what I mean is, I could peel my hands off the glass of that old mirror (noticing, all the same, how my fingerprints lingered like ten tiny faces speaking in unison and so quickly that I couldn't make out their words). And when I had sat back down in my chair I asked them again what they thought, now that they had a real poem by Cesárea Tinajero herself in front of them, with no talk in the way, the poem and nothing else, and they looked at me and then, holding the magazine between them, they plunged back into that puddle from the 1920s, that closed eye full of dust, and they said gee, Amadeo, is this the only thing of hers you have? is this her only published poem? and I said, or maybe I whispered: why yes, boys, that's all there is. And I added, as if to gauge what they really felt: disappointing, isn't it? But I don't think they even heard me, they had their heads close together and they were looking at the poem, and one of them, the Chilean, seemed thoughtful, while his friend, the Mexican, was smiling. It's impossible to discourage those boys, I thought, and then I stopped watching them and I stopped talking and I stretched, crack, crack, and one of them lifted his gaze at the sound and looked at me as if to make sure I hadn't fallen to pieces, and then he went back to Cesárea, and I yawned or sighed and for a second, distant images passed before my eyes of Cesárea and her friends walking down a street in the north of Mexico City, and I saw myself among her friends, how curious, and I yawned again, and then one of the boys broke the silence and said in a clear and pleasant voice that it was interesting, and right away the other one agreed. Not only was it interesting, he said, he'd already seen it when he was little. How? I said. In a dream, said the boy, I couldn't have been more than seven, and I had a fever. Cesárea Tina-jero's poem? Had he seen it when he was seven years old? And did he understand it? Did he know what it meant? Because it had to mean something, didn't it? And the boys looked at me and said no, Amadeo, a poem doesn't necessarily have to mean anything, except that it's a poem, although this one, Cesárea's, might not even be that. So I said let me see it and I reached out my hand like someone begging and they put the only issue of Caborca left in the world into my cramped fingers. And I saw the poem that I'd seen so many times:

And I asked the boys, I said, boys, what do you make of this poem? I said, boys, I've been looking at it for more than forty years and I've never understood a goddamn thing. Really. I might as well tell you the truth. And they said: it's a joke, Amadeo, the poem is a joke covering up something more serious. But what does it mean? I said. Let us think a little, Amadeo, they said. Of course, please do, I said. Then one of them got up and went to the bathroom and the other one got up and went to the kitchen, and I fell into a doze as, like Pedro Páramo, they wandered the hell of my house, or the hell of memories my house had become, and I let them do as they liked and I fell into a doze, because by then it was very late and we'd had a lot to drink, although from time to time I'd hear them walking, as if they were moving to stretch their legs, and every once in a while I would hear them talking, asking and telling each other who knows what, some serious things, I suppose, since there were long silences between question and answer, and other less serious things, because they would laugh, oh, those boys, I thought, oh, what an interesting evening, it's been so long since I drank so much and talked so much and remembered so much and had such a good time. When I opened my eyes again the boys had turned on the light and there was a cup of steaming coffee in front of me. Drink this, they said. At your orders, I said. I remember that while I was drinking the coffee the boys sat down across from me again and talked about the other pieces in Caborca. Well, then, I said, what's the mystery? Then the boys looked at me and said: there is no mystery, Amadeo.