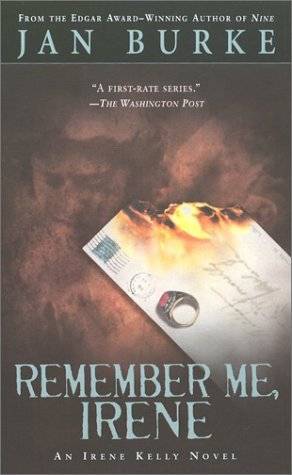

Jan Burke

Remember Me, Irene

Irene Kelly Book 04

To Thomas William Burke

WHO WELCOMED A STRANGER

There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.

– BENJAMINDISRAELI

Over and over, they used to ask me

While buying the wine or the beer…

How I happened to lead the life,

And what was the start of it.

Well, I told them a silk dress,

And a promise of marriage from a rich man…

But that was not really it at all.

Suppose a boy steals an apple

From the tray at the grocery store,

And they all begin to call him a thief,

The editor, minister, judge, and all the people-

“A thief,” “a thief,” “a thief” wherever he goes.

And he can’t get work, and he can’t get bread

Without stealing it, why the boy will steal.

It’s the way the people regard

the theft of the apple

That makes the boy what he is.

– EDGARLEEMASTERS

from “Aner Clute” inSpoon River Anthology

1

HIS LAST ADDRESSwas his own body, and what a squalid place it was. Someone told me he cleaned up just before he died, and I now know it’s true. But when I last saw him, the place was a mess.

He was sprawled on a bus bench, stinking of alcohol and urine, drooling in his sleep. He was an African American man, and while it was hard to guess his age, I judged him to be in his fifties. His skin was chapped and one of his cheeks was scraped and swollen, as if he had been in a fight. I took more than a passing interest in him: noted his matted hair, his rough beard, his rumbling snores, the small brown paper sack clutched to his chest like a prayerbook. The last prayer had been prayed out of it sometime ago, judging by the uncapped screwtop bottleneck.

I stood to one side of the bench, studying him, thinking up clever phrases to make the readers of my latest set of stories on public transportation in Las Piernas smile at my description of my predicament, smile over coffee and cereal as they turned the pages of theExpress at their breakfast tables. I would be ruthless to the Las Piernas Rapid Transit District-perhaps call it the Rabid Transient District. My small way of repaying it for forcing me to be two hours late getting back to the paper.

I had been on buses all day. My back ached and my feet hurt, and one more ride would take me back to theExpress. I was tired and frustrated. I felt a righteous anger on behalf of the citizens who had to use the system every day. I had yet to see a bus pull up at the time it was scheduled to make a stop. I could see exactly why the regular riders were angry. This was one day’s story for me; for them it would mean being late to work, to doctors’ appointments, to classes, to job interviews. One missed connection led to another, turning what was planned to be my four-hour, see-it-for-myself test ride into six hours of hell on wheels.

My series of rides had taken me all over the city, and the man before me now was not the first drunk I had encountered, not even the first sleeping drunk.

Perhaps the guilt I’ve felt since that day now colors my memory of my attitude at the time. There is, in any job that requires a person to observe other people and publish the observations, an aspect of being…well, a user. I used the man on the bench. Took notes on him.

He awoke suddenly, and I took a step back. Awake, he was a little more fearsome. He looked bigger. Stronger. He yawned, wiped a dirty sleeve across his face, and moved to a slumped sitting position. When he noticed me, he cowered away, tucking the bottle closer, eyeing me warily.

He was afraid of me. That startled me more than his abrupt awakening. I looked at the swollen cheek again as I stopped taking notes.

“Hello,” I said, and stuffed my pen and notebook into the back pocket of my worn jeans. (No, I wasn’t wearing high heels and a tight skirt. A day onbuses. I do have a little sense left, even if I am still working for theExpress.)

He just studied me, as if trying to fit me into the scheme of things, as if I were someone familiar and yet unfamiliar to him. His eyes were red and he blinked slowly and nodded forward a little, not past the danger of passing out again.

After a time, I wished he would pass out. The relentless stare began to unnerve me. I stepped a little farther away, balanced my stance, looked for potential witnesses to whatever harm he might intend. No one. This stop was along a chain-link fence surrounding an old abandoned hotel. No cars in the parking lot. Windows broken. Redevelopment, almost.

A few blocks down the way, Las Piernas could show off the benefits of its redevelopment plan. But at this end of the street, there were no polished glass skyscrapers, no new theaters or trendy nightspots. Just empty lots and crumbling brick buildings. Weeds pushing up through the neglected asphalt, curbs and sidewalks cracked. The sporadic traffic along the street moved quickly, as if the drivers wanted to get their passage along this blighted block over and done with.

I watched longingly for the bus. No sign of it.

“I know you,” he said, one careful word at a time. I looked back at him. “I know you,” he repeated. Some teeth missing. Knocked out or lost to decay?

“My picture sometimes runs in the paper,” I said. “I’m a reporter.”

He shook his head. “No.”

“Yes, really,” I said, taking another step back. “I’m a reporter for theExpress.”

Shook his head again. Kept studying me.

Where the hell was that bus?

With fumbling fingers, he started to unbutton his worn denim jacket. I was mapping out the safest place to run to when he reached down beneath several layers of T-shirts and pulled out something truly amazing: a large, gold school ring with a red stone in it, dangling from a long metal chain. He held it out toward me, swinging it back and forth like a hypnotist’s watch, and beckoned to me.

“Look at it,” he said.

“I see,” I said, in the tone one might use in speaking to a child holding a jar full of wasps. I wasn’t going to venture close enough to see which school the ring came from.

He looked up at me again and his eyes were misty. He turned away, curled his shoulders inward, as if afraid I might hit him after all.

“I’m sorry,” I said, feeling as if Ihad hit him.

He shook his head, still keeping his back to me.

Where the hell was that bus?

He turned around again, and this time, the look was pleading. “You don’t remember me. I’m…I’m…” He ducked his head. “Not who I used to be,” he mumbled.

I didn’t say anything for a moment. “I’m not who I used to be, either,” I said, ashamed.

“It’s okay,” he said in a consoling tone. “It’s okay. Okay. Okay.”

I didn’t say anything.

“You didn’t change,” he said.“I know you.” He winked at me and pointed at my face. “Kelly.”

It only took me aback for a moment. “Yes, I’m Irene Kelly.”

He grinned his misshapen grin. “I told you!”

“Yes, well, that’s what I was saying before. You’ve probably seen my picture near one of my columns in the paper.”

He shook his head and batted a hand in dismissal of that notion.

“I know you. You could help me.”

Uh-oh, I thought, here it comes. “I don’t even have fare money,” I said, holding up the transfer that would take me back to the parking lot at the paper. And my beloved Karmann Ghia. My nice, safe,private transportation. I looked up the street, and to my delight, one of Las Piernas’s diesel-belching buses was in sight.