‘Do you want to talk about it with all this lot about,’ said Joyce, looking meaningfully round the room. ‘Or just us?’

‘Joyce,’ said Millat, downing his brandy in one, ‘I don’t give a fuck.’

Joyce took that to mean just us and ushered the rest of them out of the room with her eyes.

Irie was glad to leave. In the four months that she and Millat had been turning up to the Chalfens, ploughing through Double Science, band I, and eating their selection of boiled food, a strange pattern had developed. The more progress Irie made – whether in her studies, her attempts to make polite conversation or her studied imitation of Chalfenism – the less interest Joyce showed in her. Yet the more Millat veered off the rails – turning up uninvited on a Sunday night, off his face, bringing round girls, smoking weed all over the house, drinking their 1964 Dom Perignon on the sly, pissing on the rose garden, holding a KEVIN meeting in the front room, running up a three hundred pound phone bill calling Bangladesh, telling Marcus he was queer, threatening to castrate Joshua, calling Oscar a spoilt little shit, accusing Joyce herself of being a maniac – the more Joyce adored him. In four months he already owed her over three hundred pounds, a new duvet and a bike wheel.

‘Are you coming upstairs?’ asked Marcus, as he closed the kitchen door on the two of them, and bent this way and that like a reed while his children blew past him. ‘I’ve got those pictures you wanted to see.’

Irie gave Marcus a thankful smile. It was Marcus who seemed to keep an eye out for her. It was Marcus who had helped her these four months as her brain changed from something mushy to something hard and defined, as she slowly gained a familiarity with the Chalfen way of thinking. She had thought of this as a great sacrifice on the part of a busy man, but more recently she wondered if there was not some enjoyment in it. Like watching a blind man feeling out the contours of a new object, maybe. Or a laboratory rat making sense of a maze. Either way, in exchange for his attention, Irie had begun to take an interest, first strategic and now genuine, in his FutureMouse. Consequently invitations to Marcus’s study at the very top of the house, by far her favourite room, had become more frequent.

‘Well, don’t stand there grinning like the village idiot. Come on up.’

Marcus’s room was like no place Irie had ever seen. It had no communal utility, no other purpose in the house apart from being Marcus’s room; it stored no toys, bric-a-brac, broken things, spare ironing boards; no one ate in it, slept in it or made love in it. It wasn’t like Clara’s attic space, a Xanadu of crap, all carefully stored in boxes and labelled just in case she should ever need to flee this land for another one. It wasn’t like the spare rooms of immigrants – packed to the rafters with all that they have ever possessed, no matter how defective or damaged, mountains of odds and ends – that stand testament to the fact that they have things now, where before they had nothing.) Marcus’s room was purely devoted to Marcus and Marcus’s work. A study. Like in Austen or Upstairs, Downstairs or Sherlock Holmes. Except this was the first study Irie had ever seen in real life.

The room itself was small and irregular with a sloping floor, wooden eaves that meant it was possible to stand in certain places but not others and a skylight rather than a window which let light through in slices, spotlights for dancing dust. There were four filing cabinets, open-mouthed beasts spitting paper; paper in piles on the floor, on the shelves, in circles around the chairs. The smell of a rich, sweet Germanic tobacco sat in a cloud just above head level, staining the leaves of the highest books yellow, and there was an elaborate smoking set on a side table – spare mouthpieces, pipes ranging from the standard U-bend to ever more curious shapes, snuff boxes, a selection of gauzes – all laid out in a velvet-lined leather case like a doctor’s instruments. Scattered about the walls and lining the fireplace were photos of the Chalfen clan, including comely portraits of Joyce in her pert-breasted hippy youth, a retroussé nose sneaking out between two great sheaths of hair. And then a few larger framed centrepieces. A map of the Chalfen family tree. A headshot of Mendel looking pleased with himself. A big poster of Einstein in his American icon stage – Nutty Professor hair, ‘surprised’ look and huge pipe – subtitled with the quote God does not play dice with the world. Finally, Marcus’s large oaken armchair backed on to a portrait of Crick and Watson looking tired but elated in front of their model of deoxyribonucleic acid, a spiral staircase of metal clamps, reaching from the floor of their Cambridge lab to beyond the scope of the photographer’s lens.

‘But where’s Wilkins?’ inquired Marcus, bending where the ceiling got low and tapping the photo with a pencil. ‘1962, Wilkins won the Nobel in medicine with Crick and Watson. But no sign of Wilkins in the photos. Just Crick and Watson. Watson and Crick. History likes lone geniuses or double acts. But it’s got no time for threesomes.’ Marcus thought again. ‘Unless they’re comedians or jazz musicians.’

‘ ’Spose you’ll have to be a lone genius, then,’ said Irie cheerfully, turning from the picture and sitting down on a Swedish backless chair.

‘Ah, but I have a mentor, you see.’ He pointed to a poster-sized black and white photograph on the other wall. ‘And mentors are a whole other kettle of fish.’

It was an extreme close-up of an extremely old man, the contours of his face clearly defined by line and shade, hachures on a topographic map.

‘Grand old Frenchman, a gentleman and a scholar. Taught me practically everything I know. Seventy-odd and sharp as a whip. But you see, with a mentor you needn’t credit them directly. That’s the great thing about them. Now where’s this bloody photo…’

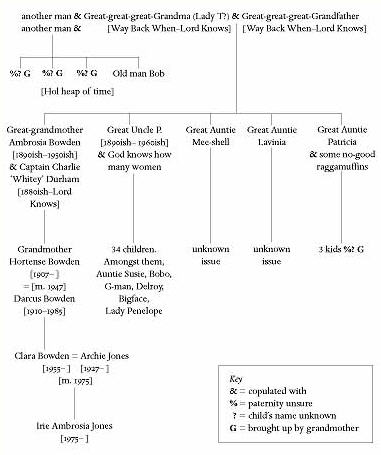

While Marcus scrabbled about in a filing cabinet, Irie studied a small slice of the Chalfen family tree, an elaborate illustrated oak that stretched back into the 1600s and forward into the present day. The differences between the Chalfens and the Jones/Bowdens were immediately plain. For starters, in the Chalfen family everybody seemed to have a normal number of children. More to the point, everybody knew whose children were whose. The men lived longer than the women. The marriages were singular and long lasting. Dates of birth and death were concrete. And the Chalfens actually knew who they were in 1675. Archie Jones could give no longer record of his family than his father’s own haphazard appearance on the planet in the back-room of a Bromley public house circa 1895 or 1896 or quite possibly 1897, depending on which nonagenarian ex-barmaid you spoke to. Clara Bowden knew a little about her grandmother, and half believed the story that her famed and prolific Uncle P. had thirty-four children, but could only state definitively that her own mother was born at 2.45 p.m. 14 January 1907, in a Catholic church in the middle of the Kingston earthquake. The rest was rumour, folk-tale and myth:

‘You guys go so far back,’ said Irie, as Marcus came up behind her to see what was of interest. ‘It’s incredible. I can’t imagine what that must feel like.’

‘Nonsensical statement. We all go back as far as each other. It’s just that the Chalfens have always written things down,’ said Marcus thoughtfully, stuffing his pipe with fresh tobacco. ‘It helps if you want to be remembered.’

‘I guess my family’s more of an oral tradition,’ said Irie with a shrug. ‘But, man, you should ask Millat about his. He’s the descendant of-’

‘A great revolutionary. So I’ve heard. I wouldn’t take any of that seriously, if I were you. One part truth to three parts fiction in that family, I fancy. Any historical figure of note in your lot?’ asked Marcus, and then, immediately uninterested in his own question, returned to his search of filing cabinet number two.