Three days:

15 October 1987

Even when the lights went out and the wind was beating the shit out of the double glazing, Alsana, a great believer in the oracle that is the BBC, sat in a nightie on the sofa, refusing to budge.

‘If that Mr Fish says it’s OK, it’s damn well OK. He’s BBC, for God’s sake!’

Samad gave up (it was almost impossible to change Alsana’s mind about the inherent reliability of her favoured English institutions, amongst them: Princess Anne, Blu-Tack, Children’s Royal Variety Performance, Eric Morecambe, Woman’s Hour). He got the torch from the kitchen drawer and went upstairs, looking for Millat.

‘Millat? Answer me, Millat! Are you there?’

‘Maybe, Abba, maybe not.’

Samad followed the voice to the bathroom and found Millat chin-high in dirty pink soap suds, reading Viz.

‘Ah, Dad, wicked. Torch. Shine it over here so I can read.’

‘Never mind that.’ Samad tore the comic from his son’s hands. ‘There’s a bloody hurricane blowing and your crazy mother intends to sit here until the roof falls in. Get out of the bath. I need you to go to the shed and find some wood and nails so that we can-’

‘But Abba, I’m butt-naked!’

‘Don’t split the hairs with me – this is an emergency. I want you to-’

An almighty ripping noise, like something being severed at the roots and flung against a wall, came from outside.

Two minutes later and the family Iqbal were standing regimental in varying states of undress, looking out through the long kitchen window on to a patch in the lawn where the shed used to be. Millat clicked his heels three times and hammed it up with cornershop accent, ‘O me O my. There’s no place like home. There’s no place like home.’

‘All right, woman. Are you coming now?’

‘Maybe, Samad Miah, maybe.’

‘Dammit! I’m not in the mood for a referendum. We’re going to Archibald’s. Maybe they still have light. And there is safety in numbers. Both of you – get dressed, grab the essentials, the life or death things, and get in the car!’

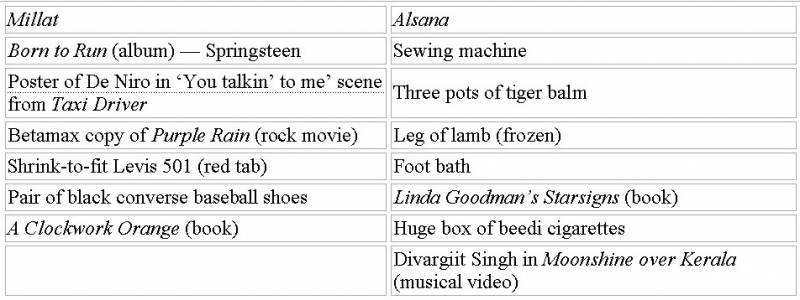

Holding the car boot open against a wind determined to bring it down, Samad was first amused and then depressed by the items his wife and son determined essential, life or death things:

Samad slammed the boot down.

‘No pen knife, no edibles, no light sources. Bloody great. No prizes for guessing which one of the Iqbals is the war veteran. Nobody even thinks to pick up the Qurān. Key item in emergency situation: spiritual support. I am going back in there. Sit in the car and don’t move a muscle.’

Once in the kitchen Samad flashed his torch around: kettle, oven hob, teacup, curtain and then a surreal glimpse of the shed sitting happy like a treehouse in next door’s horsechestnut. He picked up the Swiss army knife he remembered leaving under the sink, collected his gold-plated, velvet-fringed Qurān from the living room and was about to leave when the temptation to feel the gale, to see a little of the formidable destruction, came over him. He waited for a lull in the wind and opened the kitchen door, moving tentatively into the garden, where a sheet of lightning lit up a scene of suburban apocalypse: oaks, cedars, sycamores, elms felled in garden after garden, fences down, garden furniture demolished. It was only his own garden, often ridiculed for its corrugated-iron surround, treeless interior and bed after bed of sickly smelling herbs, that had remained relatively intact.

He was just in the process of happily formulating some allegory regarding the bending Eastern reed versus the stubborn Western oak, when the wind reasserted itself, knocking him sideways and continuing along its path to the double glazing, which it cracked and exploded effortlessly, blowing glass inside, regurgitating everything from the kitchen out into the open air. Samad, a recently airborne collander resting on his ear, held his book tight to his chest and hurried to the car.

‘What are you doing in the driving seat?’

Alsana held on to the wheel firmly and talked to Millat via the rear-view mirror. ‘Will someone please tell my husband that I am going to drive. I grew up by the Bay of Bengal. I watched my mother drive through winds like these while my husband was poncing about in Delhi with a load of fairy college boys. I suggest my husband gets in the passenger seat and doesn’t fart unless I tell him to.’

Alsana drove at three miles an hour through the deserted, blacked-out high road while winds of 110 m.p.h. relentlessly battered the tops of the highest buildings.

‘England, this is meant to be! I moved to England so I wouldn’t have to do this. Never again will I trust that Mr Crab.’

‘Amma, it’s Mr Fish.’

‘From now on, he’s Mr Crab to me,’ snapped Alsana with a dark look. ‘BBC or no BBC.’

The lights had gone out at Archie’s, but the Jones household was prepared for every disastrous eventuality from tidal wave to nuclear fallout; by the time the Iqbals got there the place was lit with dozens of gas lamps, garden candles and night lights, the front door and windows had been speedily reinforced with hardboard, and the garden trees had their branches roped together.

‘It’s all about preparation,’ announced Archie, opening the door to the desperate Iqbals and their armfuls of belongings, like a DIY king welcoming the dispossessed. ‘I mean, you’ve got to protect your family, haven’t you? Not that you’ve failed in that depar – you know what I mean – ’sjust the way I see it: it’s me against the wind. If I’ve told you once, Ick-Ball, I’ve told you a million times: check the supporting walls. If they’re not in tip-top condition, you’re buggered, mate. You really are. And you’ve got to keep a pneumatic spanner in the house. Essential.’

‘That’s fascinating, Archibald. May we come in?’

Archie stepped aside. ‘ ’Course. Tell the truth, I was expecting you. You never did know a drill bit from a screw handle, Ick-Ball. Good with the theory, but never got the hang of the practicalities. Go on, up the stairs, mind the night lights – good idea that, eh? Hello, Alsi, you look lovely as ever; hello, Millboid, yer scoundrel. So Sam, out with it: what have you lost?’

Samad sheepishly recounted the damage so far.

‘Ah, now you see, that’s not your glazing – that’s fine, I put that in – it’s the frames. Just ripped out of that crumbling wall, I’ll bet.’

Samad grudgingly acknowledged this to be the case.

‘There’ll be worst to come, mark mine. Well, what’s done is done. Clara and Irie are in the kitchen. We’ve got a Bunsen burner going, and grub’s up in a minute. But what a bloody storm, eh? Phone’s out. ’Lectricity’s out. Never seen the likes of it.’

In the kitchen, a kind of artificial calm reigned. Clara was stirring some beans, quietly humming the tune to Buffalo Soldier. Irie was hunched over a notepad, writing her diary obsessively in the manner of thirteen-year-olds:

8.30 p.m. Millat just walked in. He’s sooo gorgeous but ultimately irritating! Tight jeans as usual. Doesn’t look at me (as usual, except in a FRIENDLY way). I’m in love with a fool (stupid me)! If only he had his brother’s brains… oh well, blah blah. I’ve got puppy love and puppy fat – aaaagh! Storm still crazy. Got to go. Will write later.

‘All right,’ said Millat.

‘All right,’ said Irie.

‘Crazy this, eh?’

‘Yeah, mental.’

‘Dad’s having a fit. House is torn to shit.’

‘Ditto. It’s been madness around here too.’

‘I’d like to know where you’d be without me, young lady,’ said Archie, banging another nail into some hardboard. ‘Best-protected house in Willesden, this is. Can’t hardly tell there’s a storm going on from here.’