"'Waugh-hoo, says I. 'I'll come back at eleven to-morrow. When he wakes up give him eight drops of turpentine and three pounds of steak. Good morning.

"The next morning I was back on time. 'Well, Mr. Riddle, says I, when he opened the bedroom door, 'and how is uncle this morning?

"'He seems much better, says the young man.

"The mayor's color and pulse was fine. I gave him another treatment, and he said the last of the pain left him.

"'Now, says I, 'you'd better stay in bed for a day or two, and you'll be all right. It's a good thing I happened to be in Fisher Hill, Mr. Mayor, says I, 'for all the remedies in the cornucopia that the regular schools of medicine use couldn't have saved you. And now that error has flew and pain proved a perjurer, let's allude to a cheerfuller subject—say the fee of $250. No checks, please, I hate to write my name on the back of a check almost as bad as I do on the front.

"'I've got the cash here, says the mayor, pulling a pocket book from under his pillow.

"He counts out five fifty-dollar notes and holds 'em in his hand.

"'Bring the receipt, he says to Biddle.

"I signed the receipt and the mayor handed me the money. I put it in my inside pocket careful.

"'Now do your duty, officer, says the mayor, grinning much unlike a sick man.

"Mr. Biddle lays his hand on my arm.

"'You're under arrest, Dr. Waugh-hoo, alias Peters, says he, 'for practising medicine without authority under the State law.

"'Who are you? I asks.

"'I'll tell you who he is, says Mr. Mayor, sitting up in bed. 'He's a detective employed by the State Medical Society. He's been following you over five counties. He came to me yesterday and we fixed up this scheme to catch you. I guess you won't do any more doctoring around these parts, Mr. Fakir. What was it you said I had, doc? the mayor laughs, 'compound—well, it wasn't softening of the brain, I guess, anyway.

"'A detective, says I.

"'Correct, says Biddle. 'I'll have to turn you over to the sheriff.

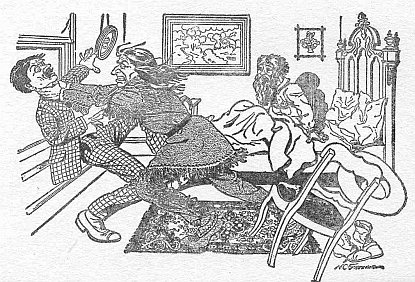

"'Let's see you do it, says I, and I grabs Biddle by the throat and half throws him out the window, but he pulls a gun and sticks it under my chin, and I stand still. Then he puts handcuffs on me, and takes the money out of my pocket.

"And I grabs Biddle by the throat."

"'I witness, says he, 'that they're the same bank bills that you and I marked, Judge Banks. I'll turn them over to the sheriff when we get to his office, and he'll send you a receipt. They'll have to be used as evidence in the case.

"'All right, Mr. Biddle, says the mayor. 'And now, Doc Waugh-hoo, he goes on, 'why don't you demonstrate? Can't you pull the cork out of your magnetism with your teeth and hocus-pocus them handcuffs off?

"'Come on, officer, says I, dignified. 'I may as well make the best of it. And then I turns to old Banks and rattles my chains.

"'Mr. Mayor, says I, 'the time will come soon when you'll believe that personal magnetism is a success. And you'll be sure that it succeeded in this case, too.

"And I guess it did.

"When we got nearly to the gate, I says: 'We might meet somebody now, Andy. I reckon you better take 'em off, and— Hey? Why, of course it was Andy Tucker. That was his scheme; and that's how we got the capital to go into business together."

Modern Rural Sports

Jeff Peters must be reminded. Whenever he is called upon, pointedly, for a story, he will maintain that his life has been as devoid of incident as the longest of Trollope's novels. But lured, he will divulge. Therefore I cast many and divers flies upon the current of his thoughts before I feel a nibble.

"I notice," said I, "that the Western farmers, in spite of their prosperity, are running after their old populistic idols again."

"It's the running season," said Jeff, "for farmers, shad, maple trees and the Connemaugh river. I know something about farmers. I thought I struck one once that had got out of the rut; but Andy Tucker proved to me I was mistaken. 'Once a farmer, always a sucker, said Andy. 'He's the man that's shoved into the front row among bullets, ballots and the ballet. He's the funny-bone and gristle of the country, said Andy, 'and I don't know who we would do without him.

"One morning me and Andy wakes up with sixty-eight cents between us in a yellow pine hotel on the edge of the pre-digested hoe-cake belt of Southern Indiana. How we got off the train there the night before I can't tell you; for she went through the village so fast that what looked like a saloon to us through the car window turned out to be a composite view of a drug store and a water tank two blocks apart. Why we got off at the first station we could, belongs to a little oroide gold watch and Alaska diamond deal we failed to pull off the day before, over the Kentucky line.

"When I woke up I heard roosters crowing, and smelt something like the fumes of nitro-muriatic acid, and heard something heavy fall on the floor below us, and a man swearing.

"'Cheer up, Andy, says I. 'We're in a rural community. Somebody has just tested a gold brick downstairs. We'll go out and get what's coming to us from a farmer; and then yoicks! and away.

"Farmers was always a kind of reserve fund to me. Whenever I was in hard luck I'd go to the crossroads, hook a finger in a farmer's suspender, recite the prospectus of my swindle in a mechanical kind of a way, look over what he had, give him back his keys, whetstone and papers that was of no value except to owner, and stroll away without asking any questions. Farmers are not fair game to me as high up in our business as me and Andy was; but there was times when we found 'em useful, just as Wall Street does the Secretary of the Treasury now and then.

"When we went down stairs we saw we was in the midst of the finest farming section we ever see. About two miles away on a hill was a big white house in a grove surrounded by a wide-spread agricultural agglomeration of fields and barns and pastures and out-houses.

"'Whose house is that? we asked the landlord.

"'That, says he, 'is the domicile and the arboreal, terrestrial and horticultural accessories of Farmer Ezra Plunkett, one of our county's most progressive citizens.

"After breakfast me and Andy, with eight cents capital left, casts the horoscope of the rural potentate.

"'Let me go alone, says I. 'Two of us against one farmer would look as one-sided as Roosevelt using both hands to kill a grizzly.

"'All right, says Andy. 'I like to be a true sport even when I'm only collecting rebates from the rutabag raisers. What bait are you going to use for this Ezra thing? Andy asks me.

"'Oh, I says, 'the first thing that come to hand in the suit case. I reckon I'll take along some of the new income tax receipts, and the recipe for making clover honey out of clabber and apple peelings; and the order blanks for the McGuffey's readers, which afterwards turn out to be McCormick's reapers; and the pearl necklace found on the train; and a pocket-size goldbrick; and a—

"'That'll be enough, says Andy. 'Any one of the lot ought to land on Ezra. And say, Jeff, make that succotash fancier give you nice, clean, new bills. It's a disgrace to our Department of Agriculture, Civil Service and Pure Food Law the kind of stuff some of these farmers hand out to use. I've had to take rolls from 'em that looked like bundles of microbe cultures captured out of a Red Cross ambulance.

"So, I goes to a livery stable and hires a buggy on my looks. I drove out to the Plunkett farm and hitched. There was a man sitting on the front steps of the house. He had on a white flannel suit, a diamond ring, golf cap and a pink ascot tie. 'Summer boarder, says I to myself.