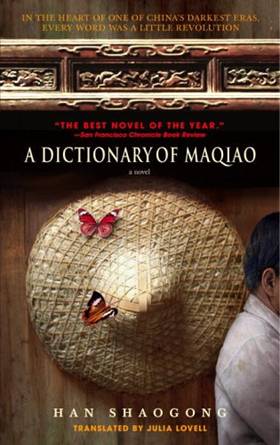

Han Shaogong

A Dictionary of Maqiao

Translated by Julia Lovell

Translator's Preface

In 1968 the Chinese Communist regime under Mao Zedong instigated one of the twentieth century's most sweeping movements of human upheaval. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76) resulted in a cataclysmic disruption of Chinese society and the relocation of millions of intellectuals, predominantly high-school and university students (zhiqing, "Educated Youth"), from the cities and towns to the countryside, where they were expected to settle for the rest of their lives, laboring alongside the peasants. Often dispatched thousands of miles to remote, impoverished areas on the borders or in the rural hinterland of China, they were confronted with languages and ways of life that were entirely alien. Han Shaogong, age sixteen in 1970, was sent to villages in northern Hunan (south China), to spend his life planting rice and tea.

That life plan came to an end in 1976, along with the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong himself. Han returned to the Hunan provincial capital Changsha, where he attended college and began a career as a writer in the post-Mao political and cultural thaw. By the mid-1980s, he was at the forefront of one of the key liberating developments in post-Mao literature: the Root-Searching Movement (xungen pai). The Root-Searchers set about reopening fiction to influences from Chinese traditional culture, aesthetics, and language, rebelling against decades of stifling Communist controls. From Mao's proscriptive 1942 Talks at Yanan on Art and Literature up until his death, the Chinese Communist Party had defined the function of literature as serving China's hundreds of millions of workers, peasants, and soldiers (whose own thoughts and desires were also defined by the Party). In the interest of increasing its control over literary production, the Maoist regime made ever more strenuous efforts to regulate language through manuals dictating correct forms of grammar, rhetoric, and characterization. After Mao's death, Han and his peers emerged, blinking, from a world in which the limits of literary expression had been so closely prescribed that fictional output had dwindled alarmingly: an average of eight novels had been published every year between 1949 and 1966; this figure fell even lower during the Cultural Revolution. [1] Not surprisingly, the question of how to break out of the strangulating "Mao Style" in language and form dominated literary discussion of the 1980s and beyond.

A Dictionary of Maqiao (completed in 1995) is, among many other things, Han Shaogong's answer to this question. It is a rebuttal both to the insanity of Maoist thought control and to the linguistic dogmatism that persists within contemporary Communist China in the form of continuing censorship of public expression. As its title suggests, the novel is structured as a dictionary. Its headings are words from the dialect of Maqiao, a tiny village in southern China, noted down by Han during his time in the countryside and confined for years in exercise books, until they became hisfocus for this philosophical meditation on the impossibilities of creating a universal, normalized language, and on the absurdities and tragedies that ensue when such an attempt is made.

The book is also a fictional account narrated by Han Shaogong as an Educated Youth, recording the history, language, and customs of the area to which he was sent down-from before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution. A Contents page appears at the start of the novel, in theory permitting the reader to treat it as a reference book or lexicon, to dip into entries at will. As the novel progresses, however, entries start to assume knowledge of dialect words and of characters already introduced-the Party Branch Secretary Benyi, the old village leader Uncle Luo, the local opera aficionado Wanyu, the special Maqiao understanding of words such as "awakened" and "precious"-thus requiring a linear reading. Han Shaogong's compilation of dictionary entries, it soon becomes apparent, is neither alphabetical nor random, and the book is very far from a dry catalog of anthropological and linguistic detail. A Dictionary is the biography of a community, told through its history, people, plants, and animals.

Through entry headings that range from people and places to dogs and mosquitoes, from brief vignettes to lengthy sequences, Han combines the variety of a short-story collection with the satisfactions of a sustained narrative. (By breaking up the narrative into shorter episodes and observations, he is also harking back to well-established genres in the Chinese literary heritage, in particular the "jottings" (biji) essay form much beloved of premodern literati.) Chinese history, in particular the traumatic recent past, has a large part to play, as Han presents his and the village's own unique interpretation and experience of events: the pre-1949 struggles between the Communist and Nationalist parties, Land Reform and the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s, the Cultural Revolution and the post-Mao economic reforms. But Han's story telling always has a larger, philosophical point to make. Even against the Orwellian backdrop of Maoist China, Han shows us, language and history do not become fixed, controllable entities; words and meanings are mutated, misrepresented, and invented by everyone, including Benyi, the local Party mouthpiece.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the novel is Han's own position as an Educated Youth-as an educated outsider living within the village. Many of the Educated Youth enthusiastically embraced the idea of banishment to the countryside as a way of assuaging the long-standing Chinese intellectual guilt complex toward the People. The legitimacy of the Chinese literary elite is traditionally rooted in the Mencian theory of government – namely, that the mandate to rule was deserved only if the People's welfare were properly attended to-and modern literati have continually agonized over how to portray the lives of the Masses, rather than the preoccupations of the group they belonged to and most understood, the urban bourgeoisie. This sense of guilt opened the way to intellectual support for Communism and, later, for the radical plan of sending millions of students to the countryside to reform their filthy intellectual thoughts by practicing the clean laboring habits of peasants.

Many of the episodes Han relates, however, testify to the difficulties these "sent-down kids" had in adjusting to the local dialect and customs, and to the tragicomic clashes between peasants and students that resulted. Han Shaogong's Maqiao is very far from being a rural paradise: life is often violent, arbitrary, and oppressive (especially for women); food is in short supply, privacy nonexistent, the work backbreaking, and the cultural and recreational possibilities limited and generally monotonous. But Han achieves a balanced portrayal of the country-dwellers he worked alongside, one that neither romanticizes nor betrays contempt for its subjects. Throughout the book, Han never behaves like a moralizing spectator, but as a guilty participant, even leader, in some of the more ridiculous and insensitive episodes. As an earnest youth with a Maoist schooling, Han is at one point instructed to write a revolutionary opera glorifying the lives of the laboring peasants. Wanyu, one of the stars of the show, reacts badly to Han's script: "Sing this? Hoes and rakes and carrying poles filling manure pits watering rice seedlings? Comrade, I have to put up with all this stuff every day in the fields, and now you want me to get on stage and sing about it?'" Han and the local "cultural officials" arrogantly tell him to get on with it-this is art.