The judge was eager to get back to the temple, but he reflected that it might be useful to have a longer conversation with Koo. He told Hoong that he could return to the tribunal, and followed Koo.

Dusk was falling. When they entered the elegant pavilion on the waterside the waiters were already lighting the colored lampions that hung from the eaves. The two men sat down near the red-lacquered balustrade, where they could enjoy the cool breeze that came over the river and the gay sight of the colored lights in the sterns of the boats that went to and fro.

The waiter brought a large platter of steaming red crabs. Koo broke a few open for the judge. He picked out the white meat with his silver chopsticks, dipped it in a plate with ginger sauce and found it very appetizing. After he had drunk a small cup of yellow wine, he said to Koo, "When we were talking in the yard just now you seemed quite convinced that the woman on Fan's farm was your wife. I didn't like to ask you this awkward question in front of Kim Sang, but do you have any reason to suppose that she was unfaithful to you?"

Koo frowned. After a while he replied, "It's a mistake to marry a woman of quite different upbringing, your honor. I am a wealthy man, but I never had any literary education. It was my ambition to marry this time the daughter of a scholar. I was wrong. Although we were together only three days, I knew she didn't like her new life. I tried my best to understand her, but there was no response, so to speak." He suddenly added in a bitter voice, "She thought I wasn't good enough for her, and since she had been educated quite liberally, I thought that perhaps a previous attachment-"

His mouth twitched; he quickly emptied his wine cup.

"It's difficult for a third person," Judge Dee said, "to pronounce an opinion when the intimate relations between a married couple are concerned. I take it that you have good reason for your suspicions. But I for one am not convinced that the woman with Fan was your wife. I am not even sure that she was indeed killed. As to your wife, you know better than I do in what complications she may have become involved. If so, I advise you to tell me now. For her sake, and also for yours."

Koo gave him a quick glance. The judge thought he detected a glint of real fear in it. But then Koo spoke evenly.

"I have told you all I know, your honor." Judge Dee rose.

"I see that mist is spreading over the river," he remarked. "I'd better be on my way. Thanks for this excellent meal!"

Koo conducted him to his palanquin and the bearers took him back through the city to the east gate. They walked at a brisk pace, they were eager to eat their evening rice.

The guards at the temple gate looked astonished when they saw the judge pass through again.

The first court of the temple was empty. From the main hall higher up came the sound of a monotonous chanting. Evidentally the monks were performing the evening service.

A rather surly young monk came to meet the judge. He said that the abbot and Hui-pen were conducting the service, but that he would bring the judge to the abbot's quarters to have a cup of tea.

The two men silently crossed the empty courtyards. Arrived on the third court, judge Dee suddenly halted in his steps.

"The back hall is on fire!" he exclaimed.

Large billows of smoke and angry tongues of fire rose high up into the air from the yard below them.

The monk smiled.

"They are preparing to cremate the almoner Tzu-hai he said. "I have never seen a cremation before," Judge Dee exclaimed. "Let's go there and have a look." He made for the stairs, but the young monk quickly laid his hand on his arm.

"Outsiders are not permitted to witness that ritual!" he said. Judge Dee shook his arm free. He said coldly, "Your youth is the only excuse for your ignorance. Remember that you are addressing your magistrate. Lead the way."

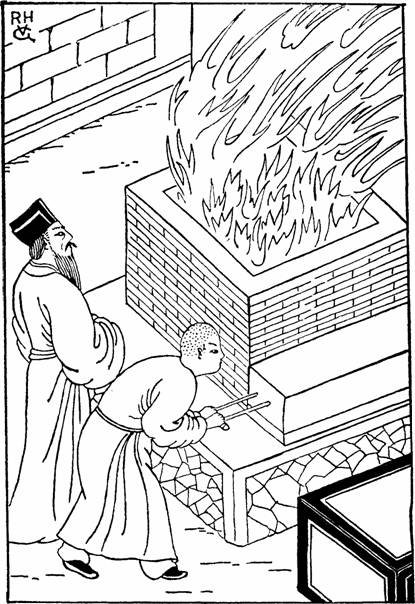

In the yard in front of the back hall a tremendous fire was burning in a large open oven. There was no one about but one monk, who was busily working the bellows. An earthenware jar was standing by his side. The judge noticed also a large oblong box lying next to the oven.

"Where is the dead body?" he asked.

"In that rosewood box," the young monk said in a surly voice. "Late this afternoon the men from the tribunal brought it here on a litter. After the cremation the ashes are collected in that jar." The heat was nearly unbearable.

"Lead me to the abbot's quarters!" the judge said curtly. When the monk had taken him up on the terrace, he left to look for the abbot. He seemed to have forgotten all about the tea. Judge Dee did not mind; he started pacing the terrace, the cool, moist air that came up from the cleft was a pleasant change after the fearful heat near the furnace.

Suddenly he heard a muffled cry. He stood still and listened. There was nothing but the murmur of the water below in the cleft. Then the cry was heard again, it grew louder, then ended in a groan. It came from the cave of Maitreya.

The judge went quickly up the wooden bridge leading across the entrance of the cave. When he had done two steps he suddenly froze. Through the haze rising up from the cleft he saw the dead magistrate standing at the other end of the bridge.

A cold fear gripping his heart, he stared motionless at the grayrobed apparition. The eye sockets seemed empty, their blind stare and the gruesome spots of decay on the hollow cheeks filled the judge with an unspeakable horror. The apparition slowly lifted an emaciated, transparent hand, and pointed down at the bridge. It slowly shook its head.

The judge looked down to where the ghostly hand was pointing. He only saw the broad boards of the bridge. He looked up. The apparition seemed to be dissolving into the mist. Then there was nothing.

A CREMATION OVEN IN A TEMPLE

A long shiver shook the judge. He placed his right foot carefully on the board in the middle of the bridge. The board dropped. He heard it crash down on the stones at the bottom of the cleft, thirty feet below.

He stood motionless for some time, staring at the black gap in front of his feet. Then he stepped back and wiped the cold sweat from his brow.

"I deeply regret to have kept your honor waiting," a voice said. Judge Dee turned round. Seeing Hui-pen standing there, he silently pointed at the missing board.

"I told the abbot many times already," Hui-pen said, annoyed, "that those moldering boards must be replaced. One of these days this bridge will cause a serious accident!"

"It nearly did," Judge Dee said dryly. "Fortunately, I halted just when I was about to cross, because I heard a cry from the cave." "Oh, they are only owls, your honor," Hui-pen said. "They have their nests near the entrance of the cave. Unfortunately, the abbot can not leave the service before he has spoken the benediction. Can I do something for your honor?"

"You can," the judge answered. "Transmit my respects to his holiness!"

He turned and walked to the stairs.