"He's only got one eye," said Hand. It was true. I scratched the dog's head. Half the animals in my life were missing an eye – growing up we'd fed nuts to a cycloptic squirrel, Terrence, that lived on our roof – and I couldn't figure out if this was good luck or bad. The dog's one eye was wide open and the other was closed tight around the vacancy. It was grinning, though – was accustomed to being appreciated. Listen my friends, I have one eye, I'm winking at you, give me some of your love. We scratched him everywhere, as he moved to guide our hands to his needs. When satisfied, the dog abruptly returned to his family. He had to get back to take care of some things.

As the tiny waves came to wet the sand with long hisses, I picked up my Churchill. Now he was at the Admiralty, whipping everything into shape, trying to increase the production of ships, honing his speechmaking skills, having the first of his children, writing beautiful letters to his Clementine. I'd never written a beautiful letter to anyone, and I had never fought the Boers, had never righted a derailed military train at Frere, never faced their artillery fire while loading wounded onto the cab and tender -

– Churchill what would you have done?

– When?

– In Oconomowoc.

– What? What are you talking about?

– I was beaten. They hit me with bats. I was in a storage unit, gathering Jack's stuff, just going through it, I guess I was lost a bit and Hand was gone -

– Where was Hand?

– He went off, up the hill.

– Hand should have been there.

– I know. But if I allow myself to know that I'll leave him, and I don't want that. I do want it, so often, but I'm stuck with him, worse off without him, if you can believe it.

– I can.

– So what would you have done?

– I can't say. The odds sound difficult.

– I would have fought next to you, Churchill. Anywhere. Did I tell you that? In India, I would have been there, leaping into musket fire. In Egypt, surveying the Dervish army at Surgham Hill, I would have been there. Cavalry, infantry, whatever -

"We should leave," I said.

"Right," Hand said.

We dressed quickly so we could drive through the countryside and tape money to donkeys. We'd been in Senegal for twenty hours and hadn't given away anything.

I drove. I drove fast. The road was dry, passing through scrubland and the occasional farm, the roadside spotted with small villages of huts and crooked toothpick fences. The terrain was dry, the grass amber. We passed more blue buses bursting with passengers, staring at us, at nothing.

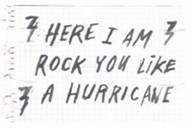

The donkey plan was Hand's. As we drove, hair still wet, we looked for donkeys standing alone so we could tape money to their sides for their owners to find. We wondered what the donkey-owners would think. What would they think? We had no idea. Money taped to a donkey? It was a great idea, we knew this. The money would be within a pouch we'd make from the pad of graph paper we'd brought, bound with medical tape. On the paper Hand, getting Sharpie all over his fingers, wrote an note of greeting and explanation. That message:

We saw many donkeys. But each time we saw a donkey, there was someone standing nearby.

"We have to find one alone, so the owner will be surprised," Hand said.

"Right."

We drove.

"This looks like Arizona," Hand said.

"It was pretty lush in the resort, though."

"Watch it."

I had driven off the road for a second, with a whoosh of gravel and a tilt of the passenger side, then back on, level and straight.

"Dumbfuck," Hand said.

"I've got it. No problem."

"Stupid. Listen."

There was a flopping sound.

"Pull over," he said.

We had a flat.

We stopped. When we got out, all was very quiet. The earth was flat and the savannah was broken only by large leafless trees, bulbous at their trunks and muscled throughout. A bright blue crazily-painted bus, full, drove by; everyone stared. The sun was directly above.

We got the spare and the tools and jacked the car up. We started on the lugnuts, but they were rusted and weren't budging. We pounded them with the wrench with no results. We sat on the highway next to the car, suddenly both very tired. The pavement was so warm I wanted to rest my face on it. I imagined what lay ahead: hitchhiking to the next town, maybe catching the bus, then finding our way to some kind of garage, then negotiations with the mechanics, a towtruck back, then, hours later, the fixing of the flat. We'd waste the day. We'd already wasted too much.

A man appeared behind the car. In a purple-black dashiki, easily seventy, with a small square jaw and eyes small and black and set deep under his brows. He said nothing.

He inserted himself between me and Hand and, without a word, took over. He first placed a rock behind the back tire, to prevent rolling. We had forgotten that. Then, crouching, with hands that hadn't, it seemed, seen moisture in decades, wrinkles white like cobwebs, he lowered the jack so the wheel rested on the road. He stood and with his sandaled old foot he kicked the wrench; the lugnut turned. He kicked again for each nut, and in a minute the tire was off.

"Leverage," Hand said to the man, touching his shoulder. "You are very good man!" he said, now patting the man on the back.

I laughed at our incompetence. The man chuckled. He looked at my face and smiled.

I put the new tire on, and the man allowed me to tighten the lugnuts myself. When the job was done the old man turned and walked away. He still hadn't said anything.

"Give him something," Hand said.

"You think?"

"Of course."

The man was now across the street, heading down the embankment and into the tall grass.

"You think it's an insult?" I said.

"No. Go."

"In America that would be an insult."

"This is different."

I grabbed a bunch of bills from my thigh pocket.

I ran after the man and when I descended the embankment I realized I was barefoot. The rough earth scratched my soles but I caught him fifty feet into the opposite field.

"Excuse me!" I said, knowing he wouldn't understand the word, but knowing I had to say something, and then settling on the words I would have said had he been able to understand. He turned to me.

I smiled and handed him a stack of bills. He stared at my nose. I smiled harder and rolled my eyes.

"Long story," I said.

He waved the money off. I took his hand and put the bills in his palm and closed his fingers, dry and ringed like birch twigs, around them. I smiled and nodded in an eager and anxious way, like I was taking his money, not giving him mine.

He said nothing. He took the bills and walked off. I jogged back to the car, my feet slapping the pavement in a happy way; a boy was there, about six years old, though there wasn't a house or hut in sight.

"Where'd he come from?" I asked.

"He just showed up," said Hand.

The boy, barefoot and wearing Magnum P.I. shorts, was leaning against the side of the car, looking inside, his hands cupped around his eyes and set against the window, reflecting the endless fields, newly tilled and dry, behind him.

"What's he want?"

"I think he was here to help."

"We have anything for him?"

"Money."

"No. He'll get robbed."

We gave him a package of white cream cookies and a liter of water, full and in the sun seeming heavy, like mercury.

We got in the car but the car wouldn't move. The boy, at the side of the car, yelled something, waving his tiny bony arms.

"The rock," said Hand.

"Oh," I said.

While watching us, carefully, holding his hand up in a gesture begging us not to run him over, the boy bent down and removed the rock. We thanked him and waved and honked and drove away, down the coast.