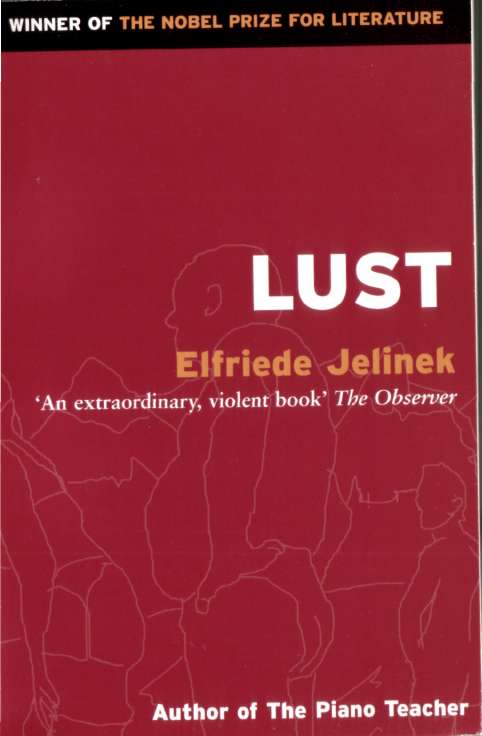

Elfriede Jelinek

Lust

Translated by Michael Hulse

The translator would like to thank Martin Chalmers and Dorle Merkel for their helpful advice

1

CURTAINS VEIL THE WOMAN in her house from the rest. Who also have their homes. Their holes. The poor creatures. Their hideaways, abideaways: their fixed abodes. Where their friendly faces abide. And all that distinguishes them is the one thing that's always the same. In this position they go to sleep: indicating their connections with the Direktor, who, breathing, is their eternal Father. This Man dispenses truth as readily as he breathes out air. That is how much his rule is taken for granted. Right now he has just about had it with women, so he says. See, there he is, yelling that all he needs is this woman. His woman. There he is, as unknowing as the trees all around. He is married. The fact acts as a counterbalance to his pleasures. This Man and his wife do not blush in each other's presence. They laugh. They have been in the past, are now and ever shall be all things to each other.

The winter sun is small at present. It is depressing an entire generation of young Europeans growing up around here or who come here for the skiing. The children of the workers at the paper mill: they might well recognize the world for what it is at six in the morning when they go to the cowshed and suddenly become strangers terrible to the animals. The woman goes for a walk with her child. She alone is worth more than half the bodies around here taken together. The other half work for the Man at the paper mill when the siren howls. And people keep a tight hold on what's closest, what's stretched out beneath them. The woman has a large clean head. She goes out walking with the child for a good hour, but the child, intoxicated with the light, would rather be rendered insensate, insensitive. By sport. The moment you take your eyes off him, he's plunging his little bones into the snow, making snowballs and throwing them The ground gleams with blood As if served up fresh. Torn birds' feathers on the snowy path. Some marten or cat has been going about its natural business, slinking about on all fours, and some creature or other has been gobbled up The carcass has been dragged off. The woman was brought here from the town, to this place where her husband runs the paper mill. The Man is not counted one of the local people; he is the only one who counts. The blood spatters on the path.

The Man He is a largish room where talking is still possible His son too has to start learning to play the violin now The Direktor does not know his workers as individuals. But he knows their total value as a workforce. Good day there, everybody! A works choir has been established. It is funded by donations. So the Direktor has something to keep him occupied. The choir travels everywhere in buses, so people can say, that's terrific. Often they have to take a stroll round little provincial towns. Off they go, with their unmeasured strides and their measureless wishes, gaping at the provincial shop windows. In the halls, the choir offers a front view of itself, its rear view turned to the bar When you see a bird in flight, all you set is the underside, too. Taking deliberate, industrious strides the songbirds ooze forth from the hired bus, which is steaming with their dung, and promptly try out their voices in the sunshine. Clouds of song rise beneath the mantling sky as the prisoners are lined up

Meanwhile their families are getting by without Father, on a small income. The Fathers eat sausages and drink beer and wine. They damage their voices and senses by using both without due care. A pity that they are of humble birth. An orchestra from Graz could take the place of every one of them. Or alternatively give them back-up. Depending what mood it was in. These awful feeble voices, cloaked in air and time. The Direktor wants them to use their voices to beg for his benevolence. Even the lowly have a chance with him if he notices that they have musical talent. The choir is the Direktor's hobby and is looked after accordingly When they are not being driven about the men are in their pens. The Direktor invests his own money when it's a matter of the bloody, stinking qualifying rounds in the regional championship. He assures himself and his singers of permanence, of continuation beyond the fleeting moment. The men, built above-ground and still building still building. So that by their works shall their wives know them when they are pensioned off But at week ends these most divine of creatures come to a weak end they don't climb the scaffolding, they climb onto a dais at the pub, and sing under compulsion, as if the dead might return and applaud The men want to be bigger, greater and lo. all their works and words want the same thing Edifying edifices

At times the woman is dissatisfied with these defects that burden her life: husband and son. The son a full colour copy, a perfect reproduction, a unique and photo-graphable child He runs along after Father so that he too will be a man one day. And Father)abs the violin in position under his chin so the foam well and truly sprays from his teeth With her life the woman answers for the smooth running of their enterprise and for good feelings each to each Via this woman the Man has passed himself on to perpetuity The woman was of the best stock that could be found and has passed herself on to the child. The child is well-behaved, except al sports, where he is allowed to run wild and needn't put up with anything from his friends, who have unanimously chosen him as the ladder to the heaven of full employment His father sees to it that he himself won't pass away from the earth He manages the factory and manages his memory, rummaging in the pockets of memory for the names of workmen who try to get out of singing in the choir. The child is a good skier, the village children are like grass beneath him. There they stand beside their shoes. The woman in her daybag, which is washed out every day, no longer goes on stage, no, she provides the child with an anchorage on her blessed coast, but the child is forever running away, taking his fire off to the poor people who live in the little houses. Intending them to find his vivacity contagious. In his fine garb he will glide across the whole world. And Father is as puffed-up as a pig's bladder, he sings, plays, yells, fucks. The choir does as he wishes, roaming from valley to mountainside, from sausage to roast, singing likewise. Never asking what they're getting paid for doing it. But the choir members are never laid off. The house is so bright that it saves on lighting costs! Indeed, its brightness is better than light. And song makes a happy home.

The choir has just arrived. Older indigenous peoples out to escape their wives. Sometimes the wives are there too, their locks stiff (sacred power of hairdressers in the country, salting these beautiful women with great pinches of permanent waves!), they have alighted from the vehicles and are having a nice day out. The choir, after all, cannot simply sing to light and air. Calmly the wife of the Direktor walks to the front on Sundays. In the village church. Where God, the mere sight of whom in pictures is an outrage, talks to her. The old women kneeling there already know what lies ahead. They know how it all ends. But still they haven't managed to find the time to learn a single thing. They work their way round from station to station of the cross, and for what? So that soon they can meet their maker, the Lord God Almighty, that hallowed member of the trinity of airhead godhead, face to face. Their slack-skinned bellies in their hands to prove their worthiness to be received. At last, time stands still. Hearing breaks loose of the detritus of a lifetime's perception of their lot. Nature is beautiful in a park and so is singing in an inn.