'South Africa.'

Arthur turned to his secretary. 'Why is everyone going to South Africa all of a sudden? Would you have an address for him there, Mr Greatorex?'

'I might have done. Except that we heard he died. Recently. November last.'

'Ah. A pity. And the house where they lived together, where Royden still lives…'

'I can take you there.'

'No, not yet. My question is… is it isolated?'

'Fairly. Like many another house.'

'So that you could enter or leave without neighbours observing you?'

'Oh yes.'

'And it is easy of access to the country?'

'Indeed. It backs on to open fields. But so do many houses.'

'Sir Arthur.' It was the first time Mrs Greatorex had spoken. As he turned to her, he noticed that her colour had risen, and she was more agitated that when they arrived. 'You suspect him, don't you? Or both of them?'

'The evidence is accumulating, to say the least, ma'am.'

Arthur prepared himself for some loyal protestation from Mrs Greatorex, a refusal to countenance his suspicions and slanders.

'Then I had better tell you what I know. About three and a half years ago – it was in July, I remember, the July before they arrested George Edalji – I was passing the Sharps' house one afternoon and called in. Wallie was out but Royden was there. We started talking about the maimings – that's what everyone was talking about at the time. After a while Royden went over to a cupboard in the kitchen and showed me – an instrument. Held it in front of me. He said, "This is what they kill the cattle with." It made me feel sick just to look at it, so I told him to put it away. I said, "You don't want them to think you are the man, do you?" And then he put it back in the cupboard.'

'Why didn't you tell me?' asked her husband.

'I thought there were enough rumours flying around without wanting to add to them. And I just wanted to forget the whole incident.'

Arthur contained his reaction and asked neutrally, 'You didn't think of telling the police?'

'No. After I got over the shock I went for a walk and thought about it. And I decided Royden was just boasting. Pretending to know something. He would hardly show me the thing if he'd done it himself, would he? And then he's a lad I've known all my life. He'd been a bit wild, as my husband explained, but since he came back from sea he settled down. He'd got himself engaged and was planning to be married. Well, he is married now. But he was known to the police and I thought that if I went and told them, they'd just make out a case against him whatever the evidence was.'

Yes, thought Arthur; and because of your silence, they went and made a case out against George instead.

'I still don't understand why you didn't tell me,' said Mr Greatorex.

'Because – because you were always harder on the boy than me. And I knew you'd jump to conclusions.'

'Conclusions which would probably have been quite correct,' he replied with a certain tartness.

Arthur pushed on. They could have their marital disagreement later. 'Mrs Greatorex, what sort of an… instrument was it?'

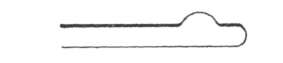

'The blade was about so long.' She gestured: a foot or so, then. 'And it folded into a casing, like a giant pocket knife. It's not a farm instrument. But it was the blade that was the frightening thing. It had a curve in it.'

'You mean, like a scimitar? Or a sickle?'

'No, no, the blade itself was straight, and its edge wasn't sharp at all. But towards the end there was a part that curved outwards, which looked extremely sharp.'

'Could you draw it for us?'

'Certainly.' Mrs Greatorex pulled out a kitchen drawer, and on a piece of lined paper made a confident freehand outline:

'This is blunt, along here, and here as well, where it's straight. And there, where it curves, it's horribly sharp.'

Arthur looked at the others. Mr Greatorex and Harry shook their heads. Alfred Wood turned the drawing round so that it faced him and said, 'Two to one it's a horse lancet. Of the larger sort. I expect he stole it from the cattle ship.'

'You see,' said Mrs Greaterex, 'your friend is jumping to conclusions immediately. Just as the police would have done.'

This time Arthur could not hold back. 'Whereas instead they jumped to conclusions about George Edalji.' Mrs Greatorex's high colour returned at this remark. 'And forgive my asking, ma'am, but did you not think of telling the police about the instrument later – at the time they charged George?'

'I thought about it, yes.'

'But did nothing.'

'Sir Arthur,' replied Mrs Greatorex, 'I do not recall your presence in the district at the time of the maimings. There was widespread hysteria. Rumours about this person and that person. Rumours about a Great Wyrley Gang. Rumours that they were going to move on from animals to young women. Talk about pagan sacrifices. It was all to do with the new moon, some said. Indeed, now I recall, Royden's wife once told me he reacted strangely to the new moon.'

'That's true,' said her husband ruminatively. 'I noticed it too. He used to laugh like a maniac when the moon was new. I thought at first he was just putting it on, but I caught him doing it when no one was about.'

'But don't you see-' Arthur began.

Mrs Greatorex cut him off. 'Laughing is not a crime. Even laughing like a maniac.'

'But didn't you think…?'

'Sir Arthur, I have no great regard for the intelligence or the efficiency of the Staffordshire Constabulary. I think that is one thing we might be agreed upon. And if you are concerned about your young friend's wrongful imprisonment, then I was concerned about the same thing happening to Roy den Sharp. It might not have ended with your friend escaping gaol, but rather with both of them behind bars for belonging to the same gang, whether it existed or not.'

Arthur decided to accept the rebuke. 'And what about the weapon? Did you tell him to destroy it?'

'Certainly not. We haven't mentioned it from that day to this.'

'Then may I ask you, Mrs Greatorex, to continue in that silence for a few days more? And a final question. Do the names Walker or Gladwin mean anything to you – in connection with the Sharps?'

The couple shook their heads.

'Harry?'

'I think I remember Gladwin. Worked for a drayman. Haven't seen him in years, though.'

Harry was told to await instructions, while Arthur and his secretary returned to Birmingham for the night. More convenient accommodation at Cannock had been proposed; but Arthur liked to be confident of a decent glass of burgundy at the end of a hard day's work. Over dinner at the Imperial Family Hotel, he suddenly remembered a phrase from one of the letters. He threw his knife and fork down with a clatter.

'When the ripper was boasting of how nobody could catch him. He wrote, "I am as sharp as sharp can be."'

'"As Sharp as Sharp can be",' repeated Wood.

'Exactly.'

'But who was the foul-mouthed boy?'

'I don't know.' Arthur was rather downcast that this particular intuition had not been confirmed. 'Perhaps a neighbour's boy. Or perhaps one of the Sharps invented him.'

'So what do we do now?'

'We continue.'

'But I thought we'd – you'd – solved it. Royden Sharp is the ripper. Royden Sharp and Wallie Sharp together wrote the letters.'

'I agree, Woodie. Now tell me why it was Royden Sharp.'

Wood answered, counting off his fingers as he did so. 'Because he showed the horse lancet to Mrs Greatorex. Because the wounds the animals suffered, cutting the skin and muscle but not penetrating the gut, could only have been inflicted by such an unusual instrument. Because he had worked as a butcher and also on a cattle ship, and therefore knew about handling animals and cutting them up. Because he could have stolen the lancet from the ship. Because the pattern of the letters and the slashings matches the pattern of his presence and absence from Wyrley. Because there are clear hints in the letters about his movements and activities. Because he has a record of mischief. Because he is affected by the new moon.'