2

These "areas of unease"-the political-social-cultural and those of the more mythic, fairy-tale variety-have a tendency to overlap, of course; a good horror picture will put the pressure on at as many points as it can. They Came from Within , for instance, is about sexual promiscuity on one level; on another level it's asking you how you'd like to have a leech jump out of a letter slot and fasten itself onto your face. These are not the same areas of unease at all.

But since we're on the subject of death and decay, we might look at a couple of films where this particular area of unease has been used well. The prime example, of course, is Night of the Living Dead , where our horror of these final states is exploited to a point where many audiences found the film well-nigh unbearable. Other taboos are also broken by the film: at one point a little girl kills her mother with a garden trowel . . . and then begins to eat her. How's that for taboo-breaking? Yet the film circles around to its starting-point again and again, and the key word in the film's title is not living but dead .

At an early point, the film's female lead, who has barely escaped being killed by a zombie in a graveyard where she and her brother have come to put flowers on their dead mother's grave (the brother is not so lucky), stumbles into a lonely farmhouse. As she explores, she hears something dripping . . . dripping . . . dripping. She goes upstairs, sees something, screams . . . and the camera zooms in on the rotting, weeks-old head of a corpse. It is a shocking, memorable moment. Later, a government official tells the watching, beleaguered populace that, although they may not like it (i.e., they will have to cross that taboo line to do it), they must burn their dead; simply soak them with gasoline and light them up. Later still, a local sheriff expresses our own uneasy shock at having come so far over the taboo line. He answers a reporter's question by saying, "Ah, they're dead . . . they're all messed up.” The good horror director must have a clear sense of where the taboo line lies, if he is not to lapse into unconscious absurdity, and a gut understanding of what the countryside is like on the far side of it. In Night of the Living Dead , George Romero plays a number of instruments, and he plays them like a virtuoso. A lot has been made of this film's graphic violence, but one of the film's most frightening moments comes near the climax, when the heroine's brother makes his reappearance, still wearing his driving gloves and clutching for his sister with the idiotic, implacable single-mindedness of the hungry dead. The film is violent, as is its sequel, Dawn of the Dead -but the violence has its own logic, and I submit to you that in the horror genre, logic goes a long way toward proving morality.

The crowning horror in Hitchcock's Psycho comes when Vera Miles touches that chair in the cellar and it spins lazily around to reveal Norman's mother at last-a wizened, shriveled corpse from which hollow eyesockets stare up blankly. She is not only dead; she has been stuffed like one of the birds which decorate Norman's office. Norman's subsequent entrance in dress and makeup is almost an anticlimax.

In AIP's The Pit and the Pendulum we see another facet of the bad death-perhaps the absolute worst. Vincent Price and his cohorts break into a tomb through its brickwork, using pick and shovel. They discover that the lady, his late wife, has indeed been buried alive; for just a moment the camera shows us her tortured face, frozen in a rictus of terror, her bulging eyes, her clawlike fingers, the skin stretched tight and gray. Following the Hammer films, this becomes, I think, the most important moment in the post-1960 horror film, signaling a return to an all-out effort to terrify the audience . . . and a willingness to use any means at hand to do it.

Other examples abound. No vampire movie can be complete without a midnight creep through the tombstones and the jimmying of a crypt door. The John Badham remake of Dracula has disappointingly few fine moments, but one rather good sequence occurs when Van Helsing (Laurence Olivier) discovers his daughter Mina's grave empty . . . and an opening at its bottom leading deeper into the earth.* This is English mining country, and we're told that the hillside where the cemetery has been laid out is honeycombed with old tunnels. Van Helsing nevertheless descends, and the movie's best passage follows-crawling, claustrophobic, and reminiscent of that classic Henry Kuttner story, "The Graveyard Rats." Van Helsing pauses at a pool for a moment, and his daughter's voice comes from behind him, begging for a kiss. Her eyes glitter unnaturally; she is still dressed in the cerements of the grave. Her flesh has decayed to a sick green color and she stands, swaying, in this passage under the earth like something from a painting of the Apocalypse. In this one moment Badham has not merely asked us to cross the taboo line with him; he has quite literally pushed us across it and into the arms of this rotting corpse-a corpse made more horrible because in life it conformed so perfectly to those conventional American standards of beauty: youth and health. It's only a moment, and the movie holds no other moment comparable to it, but it is a fine effect while it lasts.

*Van Helsing's daughter ? I hear you saying with justifiable dismay. Yes indeed. Readers familiar with Stoker's novel will see that Badham's film (and the stage play from which it was drawn) has rung any number of changes on the novel. In terms of the tale's interior logic, these changes of plot and relationship seem to work, but to what purpose? The changes don't cause Badham to say anything new about either the Count or the vampire myth in general, and to my mind there was no coherent reason for them at all. As we have to far too often, we can only shrug and say, "That's showbiz.”

3

"Thou shall not read the Bible for its prose," W. H. Auden says in one of his own finer moments, and I hope I can avoid a similar flaw in this informal little discussion of horror movies. For the next little while, I intend to discuss several groups of films from the period 1950-1980, concentrating on some of those liaison points already discussed. We will discuss some of those movies which seem to speak in their subtexts to our more concrete fears (social, economic, cultural, political), and then some of those which seem to express universal fears which cut across all cultures, changing only slightly from place to place. Later we'll examine some books and stories in about the same way . . . but hopefully we can go on from there together and appreciate some of the books and movies in this wonderful genre just for themselves-for what they are rather than for what they do. We'll try not to cut the goose open to see how it laid the golden eggs (a surgical crime which you can lay at the door of every high school English teacher and college English prof that ever put you to sleep in class) or to read the Bible for its prose.

Analysis is a wonderful tool in matters of intellectual appreciation, but if I start talking about the cultural ethos of Roger Corman or the social implications of The Day Mars Invaded the Earth , you have my cheerful permission to pop this book into a mailer, return it to the publisher, and demand your money back. In other words, when the shit starts getting too deep, I intend to leave the area rather than perform in accepted English-teacher fashion and pull on a pair of hip-waders.

Onward.

4

There are any number of places where we could begin our discussion of "real" fears, but just for the fun of it, let's begin with something fairly off the wall: the horror movie as economic nightmare.

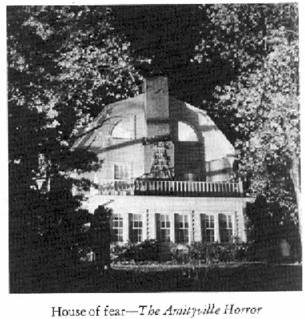

Fiction is full of economic horror stories, although very few of them are supernatural; The Crash of '79 comes to mind, as well as The Money Wolves, The Big Company Look , and the wonderful Frank Norris novel, McTeague . I only want to discuss one movie in this context, The Amityville Horror . There may be others, but this one example will serve, I think, to illustrate another idea: that the horror genre is extremely limber, extremely adaptable, extremely useful ; the author or filmmaker can use it as a crowbar to lever open locked doors or as a small, slim pick to tease the tumblers into giving. The genre can thus be used to open almost any lock on the fears which lie behind the door, and The Amityville Horror is a dollars-and-cents case in point.

There may be someone in some backwater of America who doesn't know that this film, starring James Brolin and Margot Kidder, is supposedly based on a true story (set down in a book of the same name by the late Jay Anson). I say "supposedly" because there have been several cries of "hoax!" in the news media since the book was published, and these cries have been renewed since the movie was released-and almost unanimously panned by the critics.

Despite the critics, The Amityville Horror went serenely on to become one of 1979's top-grossing movies.

If it's all the same to you, I'd just as soon not go into the story's validity or nonvalidity here, although I hold definite views on the subject. Within the context of our discussion, whether the Lutzes' house was really haunted or whether the whole thing was a put-up job matters very little. All movies, after all, are pure fiction, even the true ones. The fine film version of Joseph Wambaugh's The Onion Field begins with a title card which reads simply This is a True Story , but it's not; the very medium fictionalizes, and there is no way to stop this from happening. We know that a police officer named Ian Campbell really was killed in that onion field, and we know that his partner, Karl Hettinger, escaped; if we have doubts, let us look it up in the library and stare at the cold print there on the screen of the microfilm reader. Let us look at the police photographs of Campbell's body; let us talk to the witnesses. And yet we know there were no cameras there, grinding away, when those two small-time hoods blew Ian Campbell away, nor was there a camera present when Hettinger began hooking things from department stores and removing them from the premises via armpit express. Movies produce fiction as a byproduct the same way that boiling water produces steam . . . or as horror movies produce art.

If we were going to discuss the book version of The Amityville Horror (we're not, so relax) it would be important for us to first decide if we were talking about a fiction or a nonfiction work.