But Norman is the Werewolf. Only instead of growing hair, his change is effected by donning his dead mother's panties, slip, and dress-and hacking up the guests instead of biting them.

As Dr. Jekyll keeps secret rooms in Soho and has his own "Mr. Hyde door" at home, so we discover that Norman has his own secret place where his two personae meet: in this case it is a loophole behind a picture, which he uses to watch the ladies undress.

Psycho is effective because it brings the Werewolf myth home. It is not outside evil, predestination; the fault lies not in our stars but in ourselves. We know that Norman is only outwardly the Werewolf when he's wearing Mom's duds and speaking in Mom's voice; but we have the uneasy suspicion that inside he's the Werewolf all the time.

Psycho spawned a score of imitators, most of them immediately recognizable by their titles, which suggested more than a few toys in the attic: Straitjacket (Joan Crawford does the ax-wielding honors in this gritty if somewhat overplotted film, made from a Bloch script), Dementia-13 (Francis Coppola's first feature film), Nightmare (a Hammer picture), Repulsion.

These are only a few of the children of Hitchcock's film, which was adapted for the screen by Joseph Stefano. Stefano went on to pilot television's Outer Limits, which we will get to eventually.

10

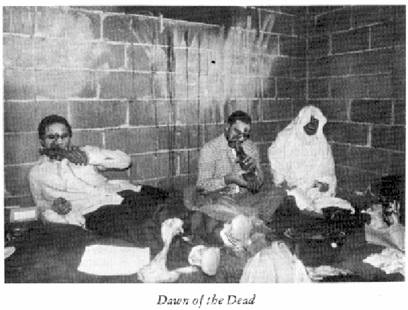

It would be ridiculous for me to suggest that all modern horror fiction, both in print and on celluloid, can be boiled down to these three archetypes. It would simplify things enormously, but it would be a false simplification, even with the Tarot card of the Ghost thrown in for good measure. It doesn't end with the Thing, the Vampire, and the Werewolf; there are other bogeys out there in the shadows as well. But these three account for a large bloc of modern horror fiction. We can see the blurry shape of the Thing Without a Name in Howard Hawks's The Thing (it turns out-rather disappointingly, I always thought-to be big Jim Arness tricked out as a vegetable from space) ; the Werewolf raises its shaggy head as Olivia de Havilland in Lady in a Cage and as Bette Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?; and we can see the shadow of the Vampire in such diverse films as Them! and George Romero's Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead . . . although in these latter two, the symbolic act of blood-drinking has been replaced by the act of cannibalism itself as the dead chomp into the flesh of their living victims.*

*Romero's Martin is a classy and visually sensuous rendering of the Vampire myth, and one of the few examples of the myth consciously examined in film, as Romero contrasts the romantic assumptions so vital to the myth (as in the John Badham version of Dracula) with the grisly reality of actually drinking blood as it spurts from the veins of the vampire's chosen victim.

It is also undeniable that filmmakers seem to return again and again to these three great monsters, and I think that in large part it's because they really are archetypes; which is to say, clay that can be easily molded in the hands of clever children, which is exactly what so many of the filmmakers who work in the genre seem to be.

Before leaving these three novels behind, and any kind of in-depth analysis of nineteenth-century supernatural fiction with them (and if you'd like to pursue the subject further, may I recommend H. P. Lovecraft's long essay Supernatural Horror in Literature? It is available in a cheap but handsome and durable Dover paperback edition.), it might be wise to backtrack to the beginning and simply offer a tip of the hat to them for the virtues they possess as novels.

There always has been a tendency to see the popular stories of yesterday as social documents, moral tracts, history lessons, or the precursors of more interesting fictions which follow (as Polidori's The Vampyre foreran Dracula, or Lewis's The Monk, which in a way sets the stage for Mary Shelley's Frankenstein)-as anything, in fact, but novels standing on their own feet, each with its own tale to tell.

When teachers and students turn to the discussion of novels such as Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Dracula upon their own terms-that is, as sustained works of craft and imagination-the discussion is often all too short. Teachers are more apt to focus on shortcomings, and students more apt to linger on such amusing antiquities as Dr. Seward's phonograph diary, Quincey P. Morris's hideously overdone drawl, or the monster's lucky grab-bag of philosophic literature.

It's true that none of these books approaches the great novels of the same period, and I will not argue that they do; you need only compare two books of roughly the same period- Dracula and Jude the Obscure, let's say-to make the point pretty conclusively. But no novel survives solely on the strength of an idea-nor on its diction or execution, as so many writers and critics of modern literature seem sincerely to believe . . . these salesmen and saleswomen of beautiful cars with no motors. While Dracula is no Jude, Stoker's novel of the Count continues to reverberate in the mind long after the more ghoulish and clamorous Varney the Vampyre has grown silent; the same is true of Mary Shelley's handling of the Thing Without a Name and Robert Louis Stevenson's handling of the Werewolf myth.

What the would-be writer of "serious" fiction (who would relegate plot and story to a place at the end of a long line headed by diction and that smooth flow of language which most college writing instructors mistakenly equate with style) seems to forget is that novels are engines, just as cars are engines; a Rolls-Royce without an engine might as well be the world's most luxurious begonia pot, and a novel in which there is no story becomes nothing but a curiosity, a little mental game. Novels are engines, and whatever we might say about these three, their creators stoked them with enough invention to run each fast and hot and clean.

Oddly enough, only Stevenson was able to stoke the engine successfully more than once.

His adventure novels continue to be read, but Stoker's later books, such as The jewel of Seven Stars and The Lair of the White Worm, are largely unheard-of and unread except by the most rabid fantasy fans.* Mary Shelley's later gothics have similarly fallen into almost total obscurity.

*In all fairness it must be added that Bram Stoker wrote some absolutely champion short stories-"The Squaw" and "The Judge's House" may be the best known. Those who enjoy macabre short fiction could not do better than his collection Dracula's Guest, which is stupidly out of print but remains available in the stacks of most public libraries.

Each of the three novels we've been discussing is remarkable in some way, not just as a horror tale or as a suspense yarn, but as an example of a much wider genre: that of the novel itself.

When Mary Shelley can leave off belaboring the philosophical implications of Victor Frankenstein's work, she gives us several powerful scenes of desolation and grim horror- most notably, perhaps, in the silent polar wastes as this mutual dance of revenge draws to its close.

Of the three, Bram Stoker is perhaps the most energetic. His book may seem overlong to modern readers, and to modern critics who have decided that one should not be expected to devote any more time to a work of popular fiction than one might devote to a made-for-TV movie (the belief seeming to be that the two are interchangeable), but during its course we are rewarded-if that's the right word-with scenes and images worthy of Dore: Renfield spreading his sugar with all the unflagging patience of the damned; the staking of Lucy; the beheading of the weird sisters by Van Helsing; the Count's final end, which comes in a hail of gunfire and a scary race against darkness.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a masterpiece of concision-the verdict of Henry James, not myself. In that indispensable little handbook by Wilfred Strunk and E. B. White, The Elements of Style, the thirteenth rule for good composition reads simply: "Omit needless words." Along with Stephen Crane's Red Badge of Courage, Henry James's The Turn of the Screw, James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice and Douglas Fairbairn's Shoot, Stevenson's economy-sized horror story could serve as a textbook example for young writers on how Strunk's Rule 13-the three most important words in all of the textbooks ever written on the technique of composition-is best applied. Characterizations are quick but precise; Stevenson's people are sketched but never caricatured. Mood is implied rather than belabored.

The narrative is as chopped and lowered as a kid's hot rod.

We'll leave where we picked this up, with the wonder and terror these three great monsters continue to create in the minds of readers. The most overlooked facet of each may be that each succeeds in overleaping reality and entering a world of total fantasy. But we are not left behind in this leap; we are brought along and allowed to view these archetypes of Werewolf, Vampire, and Thing not as figures of myth but as figures of near reality-which is to say, we are brought along for the ride of our lives. And this, at least, surpasses "good.” Man . . . that's great.