David Weber

Oath of Swords

(War God – 1)

Epigraph

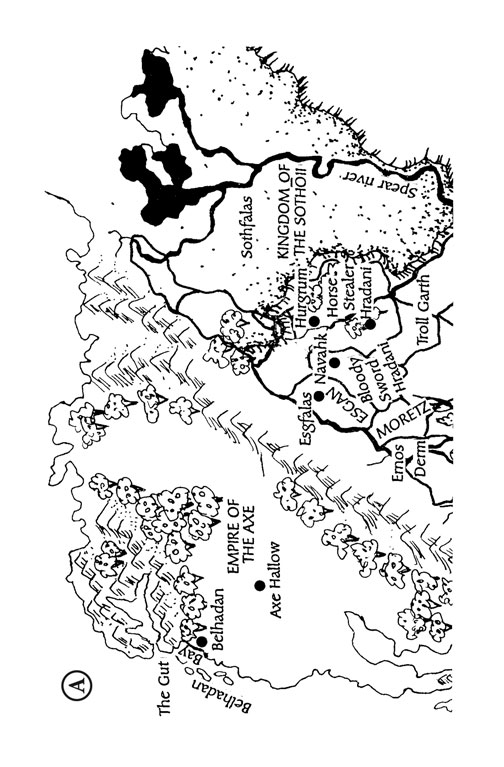

hradani

(hrä-dä-ne) n. (1) One of the original Five Races of Man, noted for foxlike ears, great stature and physical strength, and violence of temperament. (2) A barbarian or berserker. (3) Scum, brigand. adj. (1) Of or pertaining to the hradani race. (2) Dangerous, bloodthirsty or cruel. (3) Treacherous, not to be trusted. (4) Incapable of civilized conduct. [Old Kontovaran: from hra, calm + danahi, fox.]

Rage, the

(rag) n. Hradani term for the uncontrollable berserk bloodlust afflicting their people. Held by some scholars to be the result of black sorcery dating from the Fall of Kontovar (q.v.).

Strictures of Ottovar

(strik-cherz uv äh-to-vär) n. Ancient code of white wizardry enforced by Council of Ottovar in pre-Fall Kontovar. The Strictures are said to have prohibited blood magic or the use of sorcery against non-wizards, and violation of its provisions was a capital offense. It is said that the wild wizard (q.v.) Wencit of Rūm, last Lord of the Council of Ottovar prior to the Fall, still lives and attempts to enforce them with the aid of the Order of Semkirk.

– New Manhome Encyclopedic Dictionary of Norfressan Languages,

Chapter One

He shouldn’t have taken the shortcut.

Bahzell Bahnakson realized that the instant he heard the sounds drifting down the inky-dark cross corridor. He’d had to keep to the back ways used only by the palace servants-and far more numerous slaves-if he wanted to visit Brandark without the Guard’s knowledge, for he was too visible to come and go openly without being seen. But he shouldn’t have risked the shortcut just to avoid the more treacherous passages of the old keep.

He stood in an ill-lit hall heavy with the stink of its sparse torches (the expensive oil lamps were saved for Churnazh and his “courtiers”), and his mobile, foxlike ears strained at the faint noises. Then they flattened in recognition, and he cursed. Such sounds were none of his business, he told himself, and keeping clear of trouble was. Besides, they were far from the first screams he’d heard in Navahk . . . and there’d been nothing a prince of rival Hurgrum could do about the others, either.

He squeezed his dagger hilt, and his jaw clenched with the anger he dared not show his “hosts.” Bahzell had never considered himself squeamish, even for a hradani, but that was before his father sent him here as an envoy. As a hostage, really, Bahzell admitted grimly. Prince Bahnak’s army had crushed Navahk and its allies, yet Hurgrum was only a single city-state. She lacked the manpower to occupy her enemies’ territories, though many a hradani chieftain would have let his own realm go to ruin by trying to add the others to it.

But Bahnak was no ordinary chieftain. He knew there could be no lasting peace while Churnazh lived, yet he was wise enough to know what would happen if he dispersed his strength in piecemeal garrisons, each too weak to stand alone. He could defeat Navahk and its allies in battle; to conquer them he needed time to bind the allies his present victories had attracted to him, and he’d bought that time by tying Churnazh and his cronies up in a tangle of treaty promises, mutual defense clauses, and contingencies a Purple Lord would have been hard put to unravel. Half a dozen mutually suspicious hradani warlords found the task all but impossible, and to make certain they kept trying rather than resorting to more direct (and traditional) means of resolution, Bahnak had insisted on an exchange of hostages. It was simply Bahzell’s ill fortune that Navahk, as the most powerful of Hurgrum’s opponents, was entitled to a hostage from Hurgrum’s royal family.

Bahzell understood, but he wished, just this once, that he could have avoided the consequences of being Bahnak’s son. Bad enough that he was a Horse Stealer, towering head and shoulders above the tallest of the Bloody Sword tribes and instantly identifiable as an outsider. Worse that Hurgrum’s crushing victories had humiliated Navahk, which made him an instantly hated outsider. Yet both of those things were only to be expected, and Bahzell could have lived with them, if only Navahk weren’t ruled by Prince Churnazh, who not only hated Prince Bahnak (and his son), but despised them as degenerate, over-civilized weaklings, as well. His cronies and hangers-on aped their prince’s attitude and, predictably, each vied with the other to prove his contempt was deeper than any of his fellows’.

So far, Bahzell’s hostage status had kept daggers out of his back and his own sword sheathed, but no hradani was truly suited to the role of diplomat, and Bahzell had come to suspect he was even less suited than most. It might have been different somewhere else, but holding himself in check when Bloody Swords tossed out insults that would have cost a fellow Horse Stealer blood had worn his temper thin. He wondered, sometimes, if Churnazh secretly wanted him to lose control, wanted to drive Bahzell into succumbing to the Rage in order to free himself from the humiliating treaties? Or was it possible Churnazh truly believed his sneer that the Rage had gone out of Hurgrum, leaving her warriors gutless as water? It was hard to be sure of anything where the Navahkan was concerned, but two things were certain as death. He hated and despised Prince Bahnak, and his contempt for the changes Bahnak had wrought in Hurgrum was boundless.

That Bahzell understood, after a fashion, for he, too, was hradani. He understood the craving for battle, the terrible hot hunger of the Rage, and he shared his people’s disdain for weakness. But he had no use for blind stupidity, either, and what he couldn’t understand was how Churnazh could continue to think Bahnak a fool. Churnazh might sneer at Hurgrum as a city of shopkeepers who’d forgotten how to be warriors, but surely even he didn’t think it had been pure luck that Hurgrum had won every battle!

Of course, as a lad Bahzell himself had questioned some of his father’s more peculiar notions. What need did a warrior have of reading and writing or arithmetic? Why worry about tradesmen and artisans or silly things like laws governing money-lending or property rights? Where was the honor in learning to hold formation instead of charging forward to carve your own glory from the enemy’s ranks? And-despite himself, Bahzell smiled a little in memory, even now-surely bathing every single week would ruin a man’s constitution!

But he questioned no more. Hurgrum’s army hadn’t simply defeated five times its own numbers; it had slaughtered them and driven their survivors from the field in a rabble, and it had done so because it fought as a disciplined unit. Because its maps were accurate and the commanders of its fast-marching contingents, or at least their aides, could read the orders their prince sent them and close in upon their enemies in coordinated attacks. And because it was uniformly trained, because its warriors did keep formation and were equipped with weapons of its own city’s manufacture from the hands and forges of the “shopkeepers” Churnazh despised.