**Transition, everybody!**

—as Davey Golwyn’s message saved them, hauling through a tight geodesic after Gould, straight into the exiting transition, all of them expecting black space sprinkled with stars because that was the usual realspace reality, and they had been too busy to figure out where Gould’s insane trajectory had led: realspace, but not as they were used to.

All five Pilots were stunned at the blazing light of a billion suns surrounding them, dangerous in its massive magnificence, impressive and immense.

The heart of the galaxy, or near enough.

Close to the core.

Gould’s ship was behind them: some last-second shift placing them at a disadvantage, but not much. The rearmost three vessels flipped around, conjoining their communications, one of the Pilots forming the words that blasted along the high-intensity signal.

**SURRENDER OR WE OPEN—**

But something moved across the shining light of all those stars. Jed saw it, but once again it was Davey Golwyn who reacted fastest, understanding the situation.

**If you want to live, break off!**

He threw his vessel into a hard, curving trajectory; and Jed did likewise, noting that Gould was doing the same: his dark, white-webbed vessel powering in a new direction at about .9c, an immense speed in realspace.

Then a tightbeam message sounded in Jed’s ears.

**This is Max Gould. I am not the enemy. Follow me, you two.**

Jed tried to work out why Gould had said two, not five; but the mirage-like twisting of starlight intensified, and Jed-and-ship threw themselves aside then hurtled along a new path, following Gould, powered by fear because three of their number were doomed.

The trio of ships blew up.

Drifting in the braided rings of a gas giant, Jed remained silent, emitting no broadcasts. Passive visual observation showed Davey’s vessel likewise hiding. Somewhere nearby, Max Gould’s ship also floated, but out of sight.

Waiting for the enemy, whatever it was, to pass.

Max had three more deaths on his hands: not just innocents, but arguably heroes, trying to apprehend someone they thought was a criminal. Perhaps it was four deaths or more, for at least one of the pursuers in mu-space had broken off the chase during dangerous manoeuvres.

I’ll get you home.

Was that her thought or his? The ship surrounding him was infinitely comforting.

I know you will.

Perhaps they were each making the same promise to the other. Then it was time to tightbeam a signal to the two survivors.

**Follow me now. Minimal acceleration, passive sensors only.**

They were smart, given that they were still here, but he made his instructions explicit all the same. Both Pilots blipped back acknowledgements.

**And now.**

Slowly, slowly, he drifted up from the concealing planetary ring.

From this place of blazing starlight, one direction shone even more brightly, with radiation from the core itself … and there, pointing radially into shining space, the long narrow-looking line of a galactic jet, blasting its away outwards. And hanging between the jet and the three mu-space vessels, a vast space station of what looked like human construction, around which a flotilla of strange ships floated.

Several of the ships turned around.

**We’ve been spotted.**

That was Gould.

All three Pilots threw their vessels into arcing escape trajectories; then Davey Golwyn changed direction again, and lightning played across his ship’s hull as all his weapon systems powered up.

**Get the hell away!**

Whether the yell was meant for the enemy or his fellow Pilots, neither Jed nor Max would ever work out. All they could focus on was the need to fly fast and smart, away from the danger behind them.

But they saw the explosion that killed Davey even as they made their transition into mu-space.

FIFTY-TWO

EARTH, 1943 AD

The war had disrupted the university’s teaching, but Oxford retained its traditions and procedures. A new year meant the start of Hilary Term, and it was in the fifth week that Gavriela gave her first physics lecture. It was a one-off, and followed from her debriefing with the local atomic bomb developers, sharing what little she had learned in Los Alamos. She had a strong sense that the English programme lagged behind the American effort; by how far, she could not tell.

At tea following that debriefing, discussions of atomic structure and strategies for producing chain reactions naturally gravitated to college politics – though the programme was removed from academia, and its personnel included graduates of the redbrick universities – and then to general matters. A large, walrus-moustached man called Braithwaite delivered his opinion that Oxford would remain free of devastation, not because Hitler wanted to hold back from bombing the venerable sandstone architecture, but because the Luftwaffe’s aeroplanes and Rommel’s tanks were built by German women rather than their menfolk.

Stafford looked at Gavriela, and she found herself speaking.

‘Actually,’ she said, her voice mimicking the languid, fluting arrogance of the men, ‘you’ll find that the well-off German Hausfrau maintains her household with the aid of her maidservants, meaning the women are either presiding over drudges or working as such. That’s why they’ll lose the war, because Englishwomen are constructing the Wellington bombers that will blow the Wehrmacht war machine to bits.’

‘Well said, my dear.’ That was a narrow-featured man called Sanders, whose unlit pipe perched vertically in his breast pocket like a periscope, as if his unseen heart was peeking at the world. ‘And once the war is won, what do you expect to do? You personally.’

‘Teach physics, I suppose.’ Gavriela blinked. ‘I really haven’t really been thinking about life afterwards.’

At that, Braithwaite snorted and coughed out a huh: a walrus-like, barking sound to match his moustache. Afterwards, Gavriela thought that if he had not been so rude, Sanders would not have felt impelled to offer her the opportunity to speak to undergraduates, such few as remained studying while the war continued. Stafford said it was an excellent idea, effectively seconding and carrying the motion.

On the day of the lecture, she was in the room first, ahead of the students. The blackboard was one of the new kind: a tall loop of rubberized canvas stretched over horizontal rollers at ceiling height and floor. She would be able to present an extended train of argument without wiping clear the previous steps. Chalk in hand, she drew a diagram so that it would be ready before she spoke.

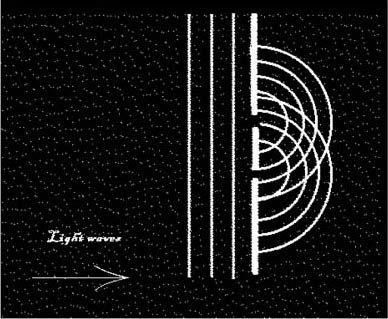

It represented linear wavefronts coming from the left, hitting a barrier with two holes in it, and propagating onwards as two sets of semicircular waves. She would have preferred to back it up with a demonstration, using a water tank with a strong light to illuminate the wave crests, but Sanders had balked when she suggested it. It was too bad, because thinking back to her first day at the ETH in Zürich, Professor Möller’s demonstration of the rubbish-basket Faraday cage had formed a spectacular memory that would be with her always.

When her audience had filed in and sat, she said, ‘Good afternoon, gentlemen. Dr Sanders tells me that you recently discussed wave-particle duality, at which point everyone’s head fell right off.’

She used her most patrician pronunciation – awf – and the students laughed.

‘So you’ll know about the double slit experiment’ – she gestured at the diagram – ‘and you see that wherever the semicircular wavefronts cross, two wave-crests are reinforcing each other. If we had a row of little fishing-floats on water waves, you can imagine them bobbing up and down strongly at those points.’