“Three-Hand,” or “Cattle” Accounting

Living beings that can be entailed, leased, loaned, bought, or sold, and that are entitled to ration allotments from their “holder,” are accounted with the so-called “three-hand,” or “cattle” system. Classed as “digits,” these entities include livestock, slaves, adopted children, widows, orphans, lower-ranks military members, various laborers, and powered vehicles, equipment, and appliances.*

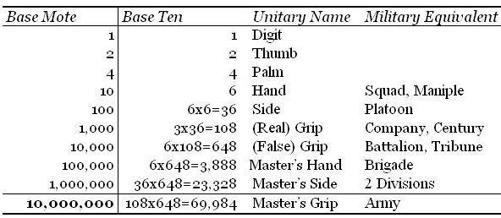

“Three-Hand,” or “Cattle” Accounting

Note that both “1,000” and “10,000” are called a “Grip.” The difference is generally inferred from context.

*A considerable body of religio-legal precedence grew from litigation surrounding classification of individuals in this schema. In this body of work, three underlying principles came to guide juridical decision-making. These were that the individual concerned (a) is not entitled to, or is incapable of, independent food production, (b) is not entitled to, or capable of, independent food procurement by other means, and (c) is entitled to be fed by someone else, as a matter of both legal and sacred obligation. By extension of these principles, powered vehicles and machinery also came to be accounted in this way. In the figurative sense, like fingers that grip and manipulate, but wither if cut off from blood supply, “digits” add power to the hand that wields them—but at a price.

In “three-hand” accounting, units 1-“10” represent the six digits of the first hand. Each unit of “10,” or a Hand, is then tallied on hand two, up to the total possible “100” (6x6=36), or a Side. Finally, each Side is transferred to the three fingers of the gripping hand, for a possible grand total of “1,000,” a Grip. Thus, in the Motie trihexagesimal system, “1,000” does not represent (6+6)2, as we might expect from our own finger-based base-10 analogy, but 6x6x3—in keeping with a Master’s finger tally.

Land Accounting

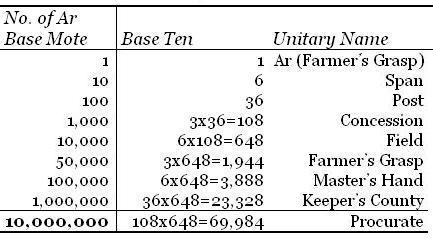

Land is measured and accounted by the “ar,” or “Farmer’s Grasp” system. Ar accounting is based, not on physical surface area, but on productivity estimates. The basic unit, an “ar,” or “Farmer’s Grasp,” represents approximately 1 cubic meter of fertile, arable soil.

In some terrain, one ar might be thinly spread over many square meters of surface area. In others, one square meter of surface might actually extend several ar deep. Land payments and allotments are made in ar by a Landholder (usually, a Master), to an ar-holder (usually, a Farmer). In return, rents and taxes are paid in produce by the ar-holder to the Landholder, Creditors, and the ar-holder’s Cattle.

Thus, it is generally in everyone’s interest to conserve and increase ar value. For the Landholder, a rise in ar promised an increase in available allotments, and the revenue derived therefrom. For the ar-holder, it meant the possibility of beating the system by getting more produce out of an allotment than it was originally worth.

However, since arability varies with moisture, friability, and other factors, a given plot of land’s value in ar was a matter of continual, intense agronomic negotiation, accounting, and legal dispute between ar-Holder and Landholder. The most vicious disputes arose at two crucial times: (1) following natural disaster, when the ar-Holder tried (often desperately) to shift the burden of responsibility for failed crops or dead Cattle onto someone else; and (2) on an ar-Holder’s death, when final reckoning for all accounts due the Landholder and other Creditors took place.

Land, or “Farmer’s Grasp” Accounting

Commodity Accounting

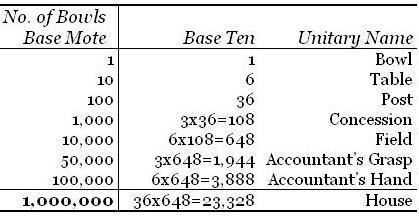

Harvested commodities and materials that are consumed in manufacturing, such as foodstuffs, ores and minerals, are subject to multiple (generally volumetric) systems of measure and reckoning. These are based upon what have come to be standardized in-kind payments and delivery quotas for the commodities in question.

Humans find transaction negotiation across these systems extremely confusing (if not outright litigious). Within the Empire of Man, such contracts are concluded using standardized pricing structures derived from ancient currency-based monetary institutions. Outside the Empire, exchange rates are set by local commodities markets—many of which are de facto pegged to the Imperial Crown.

Moties, however, have no difficulty making simultaneous calculations in several reckoning systems, while applying current, local conversion rates and standards on-the-fly. At any given time, these conversion rates and standards appear to be universally and intuitively understood by all parties, including the leveraging effects of variables like transportation costs and availability across time.

The actual negotiation process for Motie commodity barter is poorly understood. Current research suggests that Motie commodity transactions presume perfect cost-factor knowledge, and that the opening phase of any commodity barter negotiation includes an extremely rapid exchange and verification of all underlying fiduciary assumptions. Thereafter, the subject of negotiation and litigation is never one of relative commodity value. Rather, the substance of discussions seems to treat issues of rank, duty/privilege, and ability of litigants to extract commodities by force, should negotiations collapse.

Commodity, also called “Keeper’s Grasp” or “Bowl” Accounting

Asymmetry, Chimerism, and Hermaphroditism in New Utah Swenson’s Apes: An Adaptive “Gene Banking” Mechanism?

New Utah Founder’s Day Plenary Address prepared for presentation at the twenty-seventh Irregular Meeting of the New Caledonia Chapter, Interplanetary Association of Xenobiology, 2867

Introduction

I begin this paper with what will at first sound like a digression into some arcane points of New Utah history. Please bear with me: they will, in the end, prove relevant. And, for those of you unfamiliar with our little, far-away, home-grown university, this dip into our admittedly short history may even prove interesting.

Probably the best-known thing about us is the tendency among residents of Maxroy’s Purchase True Church “outback” communities to imagine (and refer to) New Utah as “heaven” or “paradise.” Indeed, this is an oft-cited example of a “Golden Age” mythology, wherein subsequent generations suppress memory of actual hardships and create legends attesting a simpler, more abundant golden age in the past. Kroeber described this phenomenon in Old American Navajo myths that attested “endless flocks” of sheep with “pastures beyond the horizon” prior to European contact—an obvious example of false reminiscence, since sheep did not exist in Navajo lands prior to European arrival.

We have had little to go on in assessing the facts of New Utah’s “golden age” presumption. Two documents existed: the New Utah True Church Founder’s Report to the Elders of Maxroy’s Purchase, filed 300 years ago by the First True Church Colony in New Utah of 2567, and the Imperial Navy’s Initial Assessment Report (IAR), filed at the turn of the following century.

The Colony Founder’s Report refers to New Utah as a land of endless, green bounty, teeming with huntable game. That Colony, founded at what is now the New Utah capital of Saint George, was laid down in the silty plains of the Oquirr river delta. As we shall see, it may well be that, at the time of landing, the plains were covered with bright green vegetation similar to Spartina grasses, as well as animals that depended on those “grasses” for sustenance. Further, at the time of founding, the True Church on Maxroy’s Purchase itself had just withdrawn to Glacier Valley. The expenses of that withdrawal were massive; as a consequence, the Saint George Colony was not well-funded, and the primary goal of the colony was to establish a self-sustaining agronomic base. In short: at its beginning, the TC colony at Saint George was fully occupied with survival, and conducted virtually no exploration outside the Saint George plains. Therefore, the Founder’s Report may in fact be accurate, if it is understood as applying to those plains, and not to New Utah as a whole.