Cliff wondered at the Sil social conventions, and their psychology. They were all in mortal danger but the Sil showed little jittery nervousness. Quert ruled absolutely. In contrast, he had to deal with ongoing questions and doubt from Aybe, Terry, and Irma. Only the need to move on, endlessly on, kept him in shaky control.

The tadfish was coming this way and as they entered the nearby forest of vine-rich trees and brush, Cliff could see it had a deft grace to its movement, though he could not see how it did so. Tendrils of vines yearned for the sun, though some turned at another angle, apparently partial to the jet’s rosy rays—specialization at work. The woods had a thick cloying stink, but were so thick overhead that the tadfish crew could not possibly see them below. Animals scampered away in their path, but there were plenty more concealed. From endless movement, Cliff had picked up ways to sense the life around them. Some animals here were superb at hiding, skinnying up into dense trees, or burrowing in hidden pits like trapdoor spiders. Others just flew away on quick stubby wings, fluttering fast enough to discourage pursuit.

Aybe and Irma walked with him, and Sils were both point and rear guards. The Sil somehow kept themselves in good order, Cliff saw, while the humans in their worn cargo pants with big flap pockets were drab and saggy. The Sil had patched those up for the bedraggled humans, back in the all-too-brief rest period following the battle with the skyfish. All that now seemed a long time ago. More wear had made their clothes ragged and rough. In contrast, the Sil had loose-fitting, lightweight tan and dusty white jumpsuits that never looked the worse for wear. They could be cleaned by just dipping them in water and connecting them to the Sil onboard and solar-powered back-batteries. Apparently some electrical method rejected ions the cloth disliked and knitted up broken fibers. The humans marveled at this.

Cliff let himself relax for a moment and enjoy the one sure thing he knew here—life: wild flocks of strange things wheeling and crying high overhead; guttural lowings and crisp cacklings from the forest around them; a smelly cloying carpet underfoot, springy, more like moss than grass, starred with bright stalks like flowers; zigzag trees silvery and ripe with flapping life, big coppery-winged things that shrieked and dived at humans when they could. Somehow the big things knew not to go after the Sil, who used their arm-arrows to slice them from the sky. Cliff hit a few with his laser and so did the others and they sank to the ground after that, going for cover.

They managed to get some sleep. Cliff woke up several times, slapping and swearing at bugs that got into his clothes. Terry kept warily watching the trees and shrubs. The spidow encounter and the bird attack had made them jumpy. There were a lot of ropy vines, and gibbering small things rushed among them, sometimes hurling down oblong red fruit as if to drive the intruders away. A Sil caught one fruit and bit into it, made a twisted face, and tossed it aside. Cliff saw a long vine move on its own and pointed. “A snake. Adapted to trees, probably disguises itself as a vine.”

Quert heard and nodded. “We call sky pirates.”

Irma chuckled. “Why?”

“Intelligent. In a way.”

“Really? What do they do with intelligence?”

“Save food for hard times.”

She stared up at the muscular, glistening snake that hung ten meters above their heads and seemed at least that long. It curled itself and leveraged onto another branch of a tall, spindly tree. Above it were cocoons of pale gray suspended among bare branches. “Like those?”

Quert gave an assenting eye-click. “Call them—” He paused, searching for the right Anglish term. “—mummies. Smart snakes store so many. Sometimes mummies we use for fertilizer.”

Aybe gaped at this and as they moved on, he said, “Mummies for … I don’t get it.”

“Closed ecology, see?” Irma shrugged. “They have to keep everything moving.”

“So does the Earth,” Aybe said. “At least, until we started industrializing space. Then we did metal smelting and manufacture in vacuum, where we could throw the wastes into the solar wind, and clean up the planet a bit.”

“But this ground ecology is just a few tens of meters deep,” Cliff said. “Has no plate tectonics. Can’t hide carbon from its air. Can’t bring fresh elements up from far below, vomit it out from volcanoes.”

Irma finished, “So you do that artificially. Plus you save resources. You might not get any more for a while. Or ever again.”

He nodded at this elementary wisdom that could always bear repeating, especially on the Bowl. They were still trying to figure out the greater scheme here, as a long-term investment. A negotiation might come up ahead, and Redwing would need to know something about those on the other side of the table.

That suited Cliff for now: seeing the Bowl as a puzzle. He had always been a problem-solver, a man who reflexively reacted to the unknown by breaking it into understandable pieces. Then Cliff would carefully solve each small puzzle, confident that the sum of such micro-problems would finally resolve the larger confusions. Irma thought the same way, one reason he liked her so much. On this endless trek through strange lands, they had grown to need each other. Every day was unnerving and wonderful at the same time, and for the same reasons. His whole team had gone into cold biostasis—always a risk—so they could reach an alien planet they knew very little about. Now they were immersed in that, multiplied by orders of magnitude. And they knew even less about this huge strange thing, the Bowl. It was daunting and thrilling, every day—in a place where there were not really days at all.

Now that they had a clear destination, the team of Sil and humans moved on with renewed energy. As they mounted a low hill, they saw the tadfish was closer. “It lands there,” Quert said, gesturing toward the next hill.

The slowly drifting football-shaped creature was maneuvering under tendrils of rain. Cliff remembered the one that had ravaged the Sil city and looked at its blister pods, wondering if the skyfish carried weapons there.

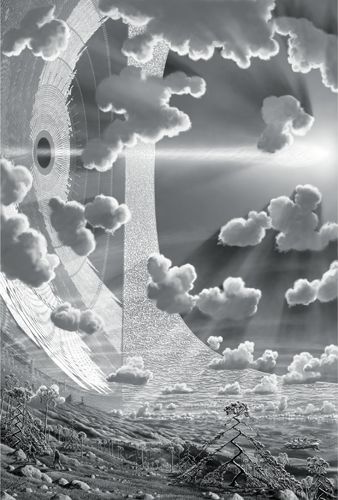

“Virga,” Aybe said. “That’s the name for when water evaporates away before hitting the ground. See? It’s falling from clumps of altocumulus clouds up there.” Among towering, steepled clouds rain fell, to be absorbed by lower, dryer layers.

“Tadfish drinking,” Quert said. “Hurry.”

They came up on the strange creature through a cluster of zigzag trees thickly wreathed in green vines. The silvery tadfish settled down in a clearing near some ceramic buildings. Quert picked up the pace. Cliff watched the complex sheen of skin as it flexed and stroked its translucent fins. Some attendants clustered at its base as it settled down. Quert was taking them in a flanking approach through the zigzag and vine maze. The ground crew was Kahalla in bright, creamy clothes. They took a small party of passengers off, and Cliff could not see who or what they were as they went into the dun-colored buildings. The Sil did not slow down.

With the humans struggling in the rear, the whole band sprinted from the last of the zigzags into the open pale dirt field and quickly across to the tadfish. They approached its face as its big green oval eyes peered down at them.

Several Sil peeled off and took up positions between the tadfish and the buildings. Cliff came out of the trees and saw some of the Kahalla ground crew turn back. They started running toward the tadfish, and the Sil moved to block them. A Kahalla drew a weapon and one Sil flexed his arm. The Kahalla went down instantly. The other Kahalla backed off and the Sil advanced.

Quert said, “They stay. Tadfish small. Not carry all of us.”