Ayaan Ali nodded. She was wearing a metallic blue scarf over her hair and resisting the urge to toy with it, Redwing noticed. This crew was good at suppressing tension and not allowing it to change the group mood. That had been a high selection criterion. She spoke slowly. “We would have time to deal with that. I am able to turn the ship quickly now. We’ve learned how to use the magnetic torque technique to gain angular momentum from the fields above their atmosphere. And we may be difficult to spot, since we will be in the jet.”

Karl nodded. Redwing saw they had now mentally stacked up the unknowns, which was a good moment to hit them with more. “Second big question: How will this not work?”

Silence. Beth said quietly, “If they have something to prevent tipping the jet awry. Something we can’t guess at now.”

“They’ve surprised us plenty before,” Ayaan Ali added.

Karl added, “Right. They’ve had lots of time to think about this.”

Clare said, “What maybe won’t work? Me. I may overestimate my ability to pilot through the jet. Beth, how bad was it?”

“An endurance test, mostly. I was driving straight up the bore, staying near the middle. Had to stay on the helm every second of the way. The big problem was keeping SunSeeker stable in the plasma turbulence. The jet is far denser than anything this ship and its magscoop were designed for. I had to max everything we had.”

Redwing wanted to add, And we nearly overheated, too, but he said instead, “Sounds hard. But we’re thinking of a fast flight through, yes?”

“I think so,” Beth said, looking at Redwing, who nodded. “Put it this way—staying alive on the Bowl was hard, too, but lots more fun.”

Their faces had grown more somber already. Most of them hadn’t been revived when SunSeeker flew up the jet and through the Knothole, but they had heard about the long hours of a creaking, groaning ship, and the dizzy swirls when they yawed and nearly tumbled. Their eyes turned introspective. He decided to loosen them up.

“Y’know, way back when I was in nav school, I asked an instructor, ‘Why do people take such an instant dislike to me?’ At first the woman didn’t want to answer. But I nagged her and finally she said, ‘It saves them time.’”

When their laughter died down—he could read their tensions by that measure, too—he said, “Point is, I’m a bug about details. Made me pretty damn obnoxious in nav school and ever since.” He gave them a smile. “I learned that in nav and tactics and all the rest. Space doesn’t forgive anybody. So we have to simulate all the troubles we can see coming.”

Karl said, “And then?”

“I’ll throw some unknowns you hadn’t thought of into the simulation, the training pod, all the rest. I want you to expect the unexpected.”

They nodded and for half an hour they tossed around possible unknowns. Then he said, “Question three: Will you please shoot as many holes as possible into my thinking on this?”

This led to more scattershot thinking, more debate. The jet was the big problem, and there were many ways to look at it. Redwing waved his hand in a programmed way, and the bridge wall lit up with a photo of the Bowl made when they were on the approach from the side. This was when Redwing and the small watch crew, plus Cliff and Beth, were just trying to grasp the concept of the Bowl. That now seemed so long ago, but it was less than a year.

Some of them must not have seen it before, because it brought gasps.

“I’d forgotten how beautiful it is,” Beth said.

Clare said wistfully, “Some of us have only seen it up close. We missed a lot.”

Fred pointed. “Notice how it flares out from its star, then narrows down a lot. That’s the magnetic stresses working. Wish I knew how they do it.”

Karl said, “I’ve fished around in the thousands of images SunSeeker’s Omni-survey Artilect made on our approach. That’s when we got far enough ahead, while we were making our long turn to rendezvous. By the way”—a nod to Beth—“that was brilliant navigation. Hitting a moving target on an interstellar scale.”

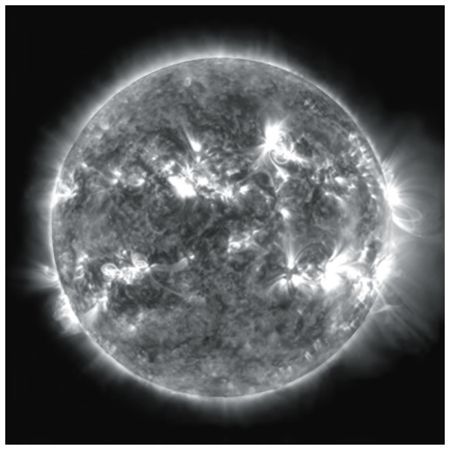

“This was all-spectra?” Fred asked.

“Exactly. Here is a view of the other side of their star. Away from the jet. It’s in spectral lines specified to bring out the magnetic structures visible in their solar corona.”

Ayaan Ali said, “Star acne,” one of her rare jokes. She even blushed when everyone laughed.

Beth said hesitantly, “Those are all … magnetic storms?”

“Not storms, though on our sun, they would eventually blow open and make storms. Those loop structures are anchored in the star’s plasma. Think of the magnetic fields as rubber bands. The plasma holds them down, and when they get free they stretch away from their feet. They’re stable, at least for a while. Lots of magnetic field energy in those things. They move, just like the ones on our sun. But in the long run they move toward the edge we see and migrate. Over to the other side.”

Before Karl could go on, Fred said, “To the jet.”

Karl chuckled. “I should know somebody’d steal my thunder. Fred’s good at that.”

“So the other side of their star, which we can’t see—”

“Is a magnetic farm, sort of?” Clare said skeptically.

Karl chuckled again. “You guys are too fast. Yep, Clare, that’s where the star builds big magnetic loops and swirls. Then they drift over to our side of the star. They gang up around the foot of the jet. Then they merge—don’t ask me how. That feeds magnetic energy into the jet—builds it, I guess.” He shrugged. “I don’t have a clue about how this gets done.”

All but Karl had blank, big-eyed stares. Redwing watched them digest the scale of the whole thing for a long moment. Star engineering, he thought. Somehow we missed that in school.…

“There’s a real problem here,” Ayaan Ali said. “These Folk aliens you talked to, Captain—did they seem like beings who could command a star?”

Redwing pursed his lips. He liked to let things speak for themselves, and so had not kept the recording of his talk with Tananareve away from the crew. The more heads working these problems, the better. They had intuitions about the Folk, too, and now was the right time to let them come out. So he just nodded to Beth with raised eyebrows.

Beth said, “You’ve all seen my pictures of the one who interrogated us, Memor. Plus all the assistants—so much smaller, they seem like another species entirely. Probably they are, but they work together in what looked to us like a steep hierarchy. Impressive, that Memor—especially in bulk. But a creature that could manage a star?” She arched a skeptical eyebrow and let her mouth turn down in a comic show of doubt.

This brought smiles all round the table. “My point exactly,” Ayaan Ali said. “How would anything our size—hell, any size—made out of ordinary matter, control solar magnetic loops?”

“Good point,” Fred said. “There’s something else going on.”

“But what?” Redwing said.

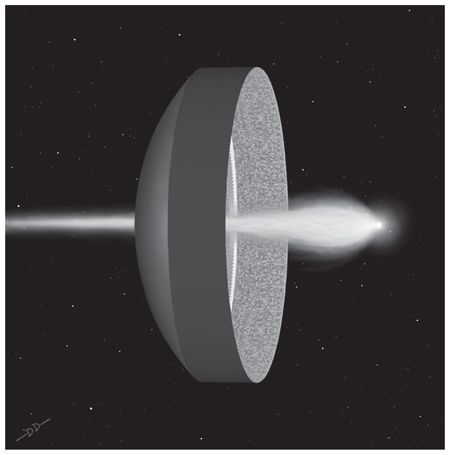

No answers. They were all thinking, and he saw it was time to get back to work. He flicked another image on the view wall. “Here’s a later view as we came around in advance of their star.”

This brought more quiet ooohs and aahhhs.

“Here’s where we see the point about those magnetic loops,” Karl said. Fred was already nodding. “See how the jet seems to curl around? Those are—”

“Magnetic helices,” Fred cut in. “The corkscrew threads are brighter, because the field strength is stronger there, and so is the plasma density. Classic stuff. Way back a century or two ago, we saw all that in the big jets that come out of disks around black holes. Astronomers know plenty about these.”

“Uh, thanks.”

Redwing could tell Karl was getting irked with Fred’s butting in. But Karl was holding himself back with admirable restraint. And Fred’s point was well taken. Redwing said mildly, “So to get the idea for this, whoever built it had only to look into the night sky. At other galaxies, same as we did back in the—what, twenty-first century?”