“There’s a difference?”

She smiled. “It was in a big park, elaborate buildings, the works.”

Fred wobbled into the mess. Beth was feeling frail, too; there were handholds everywhere, and she used them. Surely she’d been longing for foods of Earth? There had been almost no red meat in the parts of the Bowl she’d seen. Beef curry? Its tang enticed. The mess was neat, clean, like a strict diner. Already Fred had picked a five-bean salad and a cheese sandwich.

Redwing dialed up a chef’s salad. “We’re recording everything we can get in electromagnetics from the Bowl surface, but there’s not much,” he said.

Beth asked, “What are you doing with our allies? I mean the—”

“Snakes? They kind of give me the willies, but they seem benign. We’re helping the finger snakes unload that ship you hijacked. Those plants will do more for them than for us, don’t you think? Shall we house them in the garden? We’ll have to work out what to give them in the way of sunlight and dirt and water. Want to watch?” Redwing finger-danced before a sensor.

The wall wavered, and yes, on the visual wall there were finger snakes and humans moving trays out of the magnetic car. Beth saw these were new crew. Ayaan Ali, pilot; Claire Conway, copilot; and Karl Lebanon, the general technology officer. The ship’s population was growing. They moved dexterously among the three snakes, struggling with the language problem.

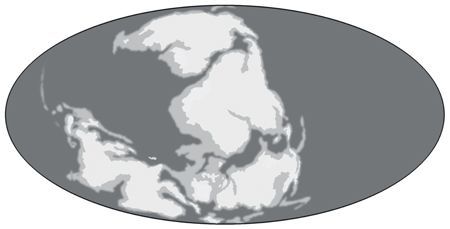

Beth muted the sound and watched while she ate. Silence as she forked in flavors she had dreamed of down on the Bowl. No talk, only the clinking of silverware. Then Fred said, “The map in the big globe? It looked alien, but it’s blue and white like an Earthlike planet.”

“Could that have been Earth in the deep past?”

“Yeah. A hundred million years ago?”

Redwing said, “Ayaan says no. She pegs that clump of migrating continents to the middle Jurassic. Your picture was upside down, south pole up. Argue with her if you don’t agree.”

Fred shook his head. “I can recall it, but look—I sent Ayaan my photo file, so—”

Redwing called up a wall display. “There is a lot of spiky emission from that jet. Seems like message-style stuff, but we can’t decipher it. Anyway, it fuzzed up your pictures and Ayaan had a tedious job getting it compiled. She compiled, processed, and flattened the image store. Piled it into a global map, stitching together your flat-on views—here.”

Fred read the notes. “Of course … All those transforms have blurred out the details, sure. So now, look at South America. Just shows what looking at things upside down and only one side, will do. Now, rightside up and complete, I can see it. How could I have missed it?”

Beth said kindly, “You didn’t, not really. We were on the run, remember? And this doesn’t look a lot like Earth, all the continents squeezed together. But you were right about the Bowl having some link to Earth. Tell the cap’n your ideas.”

Fred glanced at Redwing, eyes wary. “I was tired then, just thinking out loud—”

“And you were right.” Beth opened her hands across the table. “Spot on. Sorry I didn’t pay enough attention. So, tell the cap’n.”

Fred gazed off into space, speaking to nobody. “Okay, I thought … wow, Jurassic. A hundred seventy-five million years back? That’s when the dinosaurs got big. Damn. Could they have got intelligent, too? Captain, I’ve been thinking that intelligent dinosaurs built the Bowl and then evolved into all the varieties of Bird Folk we found here. Gene tampering, too, we saw that in some species—you don’t evolve extra legs by accident. They keep coming back to Sol system because it’s their home.” Fred remembered his hunger and bit into his cheese sandwich.

A smile played around Redwing’s lips. “If they picked up the apes a few hundred thousand years ago, then they could have been en route to Glory for that long. They’re definitely aimed at Glory, just like we were. Beth?” Beth’s mouth was full, so Redwing went on. “All that brain sweat we spent wondering why our motors weren’t putting out enough thrust? The motors are fine. We were plowing through the backwash from the Bowl’s jet, picking up backflowing gases all across a thousand kilometers of our ramjet scoop, for all the last hundred years of our flight.”

Beth nodded. “We could have gone around it. Too late now, right? We’ll still be short.”

“Short of everything. Fuel. Water. Air. Food. It gets worse the more people we thaw, but what the hell, we still can’t make it unless we can get supplies from the Bowl. And we’re at war.”

“Cliff killed Bird Folk?”

“Yeah. And they tried to repay the favor.”

* * *

Beth had expected some shipboard protocols, since Redwing liked to keep discipline. But the first thing Redwing said when they got to his cramped office was, “What was it like down there?”

Across Beth’s face emotions flickered. “Imagine you can see land in the sky. You can tell it’s far away because even the highest clouds are brighter, and you can’t see stars at all. The sun blots them out. It gives you a queasy feeling at first, land hanging in the distance, no night, hard to sleep…” She took a deep breath, wheezing a bit, her respiratory system adjusting to the ship after so long in alien air. “The … the rest of the Bowl looks like brown land and white stretches of cloud—imagine, being able to see a hurricane no bigger than your thumbnail. It’s dim, because the sun’s always there. The jet casts separate shadows, too. It’s always slow-twisting in the sky. The clouds go far, far up—their atmosphere’s much higher than ours.”

“You can’t see the molecular skin they have keeping their air in?”

“Not a chance. Clouds, stacking up as far as you can see. The trees are different, too—some zigzag and send long feelers down to the ground. I never did figure out why. Maybe a low-grav effect. Anyway, there’s this faint land up in the sky. You can see whole patches of land like continents just hanging there. Plus seas, but mostly you see the mirror zone. The reflectors aren’t casting sunlight into your eyes—”

“They’re pointed back at the star, sure.”

“—so they’re gray, with brighter streaks here and there. The Knothole is up there, too, not easy to see, because it’s got the jet shooting through it all the time. It narrows down and gets brighter right at the Knothole. You can watch big twisting strands moving in the jet, if you look long enough. It’s always changing.”

“And the ground, the animals—”

“Impossible to count how many differences there are. Strange things that fly—the air’s full of birds and flapping reptile things, too, because in low grav everything takes to the sky if there’s an advantage. We got dive-bombed by birds thinking maybe our hair was something they could make off with—food, I guess.”

Redwing laughed with a sad smile and she saw he was sorry he had to be stuck up here, flying a marginal ramscoop to make velocity changes against the vagrant forces around the Bowl. He didn’t want to sail; he wanted to land.

She sipped some coffee and saw it was best that she not say how she had gotten a certain dreadful, electric zest while fleeing across the Bowl. Redwing asked questions and she did not want to say it was like an unending marathon. A big slice of the strange, a zap to the synaptic net, the shock of unending Otherness moistened with meaning, special stinks, grace notes, blaring daylight that illuminated without instructing. A marathon that addicted.

To wake up from cold sleep and go into that, fresh from the gewgaws and flashy bubble gum of techno-Earth, was—well, a consummation requiring digestion.

She could see that Redwing worried at this, could not let it go. Neither could she. Vexing thoughts came, flying strange and fragrant through her mind, but they were not problems, no. They were the shrapnel you carried, buried deep, wounds from meeting the strange.