I have flown in choppers when bullets have been cracking through the cabin and the skin was like a sieve – I’ve never had one let me down. All chopper crews are either heroes or crazy – I think it is in the job description. Many is the time chopper crews have come in under punishing fire to take out our wounded without a thought for their own safety.

The crew sit in armoured seats and the twin engines are surrounded by armour which is some help. The rotor blades are so tough they will cut the top off a telegraph pole. Seriously, I’ve seen this in the sales video. A chopper will run on one engine and, unlikely as you might think, if it loses both engines it can alter the pitch of the rotor in a manoeuvre called ‘auto-rotation’ and effectively glide into a bumpy, but survivable, landing from any height. I’m not going to tell you the sensitive spots for obvious reasons. The crew may get blast and small-arms wounds but when a chopper comes down it has either been hit by an anti-aircraft missile or been very, very unlucky. They are my favourite form of transport so I may be a little biased but choppers have saved my neck more times than I can count.

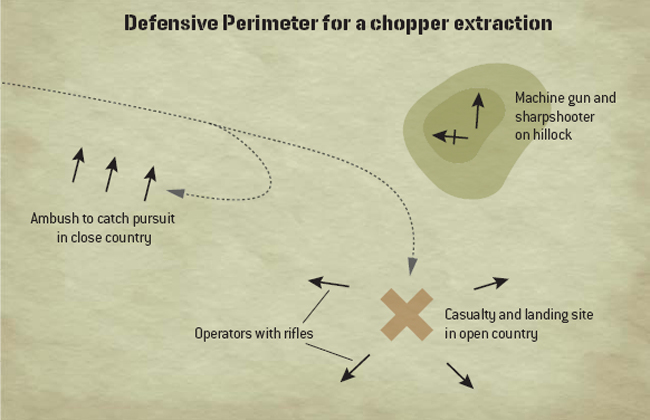

The object of the exercise is to prevent the enemy destroying the helicopter on the ground as it loads the troops. Where there is long distance visibility over open ground the riflemen just form a rough circle around the landing site facing out. The sharpshooter and the machine gun are placed on the hillock to prevent the enemy occupying it and give better range/visibility for them. The casualty is placed close to the landing site. Where the cover is close and visibility short range, as in forest or jungle, the enemy cannot see the landing site from a distance so the only way they can find their way to the position in time to attack it is by following the section. To avoid this the section forms a dog-leg ambush as they approach the landing site as shown at the top left of this diagram. In a hot extraction, where the section is in contact with the enemy, a gunship would accompany the extraction helicopter and strafe the enemy before a landing was attempted.

A group of prisoners are loaded aboard a UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter at Camp Korean Village, Iraq, 7 March 2006. (USMC)

A Merlin, with the back door down, and a gunner on watch, landing by a British Parachute Regiment patrol. (Photo courtesy Tom Blakey)

A Chinook loading troops en route to an operation in the Upper Sangin Valley, Afghanistan. (Rupert Frere © UK Crown Copyright, 2009, MOD)

A chopper can, provided it is not overloaded, come in and go out steeper than a fixed-wing but taking off and landing are still the dangerous times. As you will not always be landing on an airfield from a chopper, when you do come down onto an area that is not secure get out there to the appropriate distance required by the ground and set up the defensive perimeter.

When you are waiting for a chopper to collect you make sure there is a good perimeter defence around where it is coming in to land. Don’t use the same place regularly.

If you let one crew get shot up by idleness then the others may not be so quick or heroic in getting you out of a sticky spot. Protect the choppers with a perimeter defence and they will look after you.

For the purpose of this discussion I am going to define artillery as heavy guns firing shells of various kinds, mortars, rockets fired from the ground or from aircraft with various contents, and bombs dropped from aircraft with various contents. My reasoning is that at the receiving end of these it makes little odds how they get to you and the defence against them is much the same once you understand what they can do. It is also the case from a strategic planning point of view that ground-attack aircraft are just very long-range artillery with limited ammunition.

Operating these expensive, high tech weapons takes a great deal of brains and training. Defending against them does not. The principle defence against all these weapons – aside from a gas or chemical attack – is the simple hole in the ground. In conventional warfare any and all of these weapons may be deployed against you. In counter-insurgency warfare the main threats are rocket propelled grenades and mortars firing high explosive shells. I am covering the remainder because you never know what is going to kick off next and if you find yourself up against real artillery in a real war you will be better prepared.

HIGH EXPLOSIVE BOMBS AND SHELLS

High Explosive is a chemical which burns very quickly and turns into a larger quantity of gas than the original volume of explosive. This means it expands suddenly and pushes the surrounding air out of the way creating a shockwave which pushes or mushes whatever it comes into contact with. In words this does not sound very threatening until you know about VOD. An explosive is defined as high, medium or low by its VOD or velocity of detonation.

An Israeli Army 155mm mobile artillery piece fires into southern Lebanon from a position on the frontier, 13 July 2006. (Corbis)

The VOD is how fast the burn travels through the explosive and is expressed as metres per second. The idea is that the faster the burn the greater the shockwave. To give you an idea of what I am talking about here, a home-made explosive such as AMFO is a medium explosive with a VOD in the region of 2,500 metres per second whereas a high explosive such as PE4 has a VOD over 5,000 metres per second. If you had a strip of it 5km long and detonated one end then the burn would reach the other end a second later. Pretty quick hey?

Shrapnel damage to a truck after roadside bomb attack in Baghdad, 17 April 2006. This was an IED rather than a shell but photo shows the shrapnel damage well and the principle is exactly the same. (Corbis)

A pure blast will kill you if it is close enough – and not-so-close I can tell you it feels like being kicked all over at the same time – but a small explosive charge with a little scrap iron around it can do far more damage to more people as the shrapnel travels in all directions like a thousand bullets. Shrapnel is the name given to steel or iron projectiles driven by an explosive charge. Sometimes the shrapnel may be ball bearings or nails but generally it is the splintered casing of the bomb or projectile similar to an old Mills Pineapple Grenade. There is also the prospect, with the advance of technology, for terrorists to be able to deliver all manner of nasty things by mortar or shell and I shall cover these in their place so you won’t be living in happy ignorance.

The common shrapnel artillery shell or mortar bomb is a brittle iron casing filled with explosive and fused to explode in one of three situations to defeat different target types: on impact with the ground, in the air above the ground with a timer/radar or underground with a timer or delayed fuse. Timed/radar fuses to achieve air or underground bursts are tricky to use and not really a terrorist or even infantry weapon. They are usually employed by experts such as artillery units or the navy – although recently Western 120mm mortars have been issued with radar-fused air-bursting bombs. Nevertheless I will explain all three so you know what you are missing.

Shells from cannon and bombs from aircraft can also do all manner of clever thing such as splitting into smaller units called ‘bomblets’ as they approach the target but this is fine tuning to make sure everyone gets a piece and does not concern us here. The thing to remember is that when someone is firing explosive ordnance at you the best place to be is in a hole. Preferably with a roof.