Firstly, have you ever heard that phrase before? If not, you are not alone. This section is about what I learned as ‘Fire and Movement’ or the ‘Buddy Buddy System’. The thing is, just about every army in the world has it and uses a different name for the same thing. The idea is that when you are out on patrol and you come under fire there needs to be an SOP for you to get on with for a few moments while the unit commander figures out what to do. Individual Movement Techniques is that SOP.

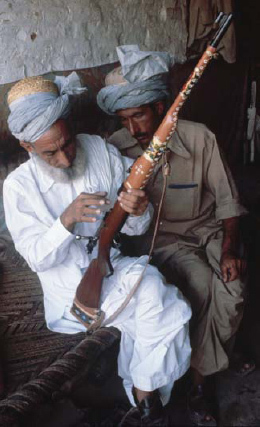

Two Pathan tribesmen examine a painted Lee-Enfield .303 rifle at the village of Darra Adam Khel, 26 August 1980. The old bolt-action rifles are still incredibly accurate at long ranges. (Corbis)

Suppose you come under fire from the flank while you are walking in single file. What do you do? You turn to face the enemy and work in pairs to advance on him. One man takes up a firing position and lays down suppressing fire while the other moves forward a few yards or as the ground allows. Then he lays down suppressing fire and the first man moves past him. By this means the unit advances on the enemy steadily until he either runs or is destroyed.

In combat, this is supposed to allow the first few moments of the engagement to occur almost automatically and gives the soldiers a way to respond appropriately and predictably while the unit commander evaluates the situation prior to issuing orders. I think this is a load of bollocks. All it does is get men killed. The correct answer to coming under effective fire is to hit the ground or run for the nearest cover as seems most useful – shooting as you go. Then you try to get some rounds off at the enemy to suppress his fire while the unit leader decides what you are going to do. This might be fire and movement towards the enemy or it might not. More likely it will be suppressing fire while you call in air support or while you set up a fire group and an assault group to advance on the enemy when he has his head down.

Bullshit...

Let me just get something else out of the way here. If you look at some of the thousands of soldiers’ groups on Facebook, or magazines relating to soldiering, you will see all sorts of fancy guns and gadgets to make your gun work better. There are special grips, special aiming sights, special light fittings and on and on. This is almost all entirely bullshit.

Gadgets are to reassure a timid soldier who is not confident of his, or his team’s, ability. I want you to be so good at your job you have confidence in yourself and your mates not your hardware. Then if the kit goes missing or breaks down you still have the important part of the operation – yourself. Do you find that hard to believe? Consider this:

Super soldiers?

Imagine a dozen SEALs or SAS operators armed only with bolt-action rifles from World War II. They are loose in a forest and set against a dozen infantry soldiers armed with every gadget and new bit of kit they can carry. Who would you bet on? The Special Forces I would imagine.

Why? Maybe you picked the SF because you think they are supermen. If so, you are right for the wrong reason. The reason the SF would win with no or relatively few casualties is because of a couple of simple factors:

A good plan:They are thoroughly trained and have experience so they are calm and collected. And so they can put a good plan together using the right tactics for the situation.

Commitment:When they have settled on a plan they will carry it out with no hesitation or lack of commitment. In their minds there is no more thought of losing than a butcher might expect a piece of beef to get up and walk away. And, of course, they will never give up.

My Plan

I was asked by my editor what I would do in this situation. She thinks people might want to know how it should be done. So at risk of going off the subject...

Training first: I would get my team very comfortable with the old rifles and get them ‘shot in’ so the iron sights are set correctly for each man. A decent shot will maintain a 12in group at 300 yards or better and bringing that group onto centre of mass will make him deadly.

Remember KISS? (Keep It Simple Stupid): We would hide for about three weeks until the infantry soldiers got tired and cold and sloppy from not seeing us. Most likely they would be patrolling every day and getting wet and tired then doing stags at night. I would use one or two men to watch their movements and see where they went each day while the others made themselves comfortable as far away as possible. Then, when they let their guard down, I would launch one ambush from 200–300 yards and expect to kill half of them. Then withdraw. Why? Because the old bolt-action rifles have the advantage of greater accuracy and range over the modern infantry rifle. In response I would expect the survivors to take themselves and their wounded to a position they could defend. It would be interesting to see how well they dug in. Again, I would give them two or three weeks to think we had left, then I would hit them at dawn from the greatest distance we could get a clear shot. This might leave one or two alive so let them stew for a week or two and repeat. Job done.

FIELD-CRAFT AND CAMOUFLAGE

Field-craft and camouflage is how you avoid being seen, and therefore shot at, while you are moving through country or laying quietly waiting to give someone a surprise. First of all you need to make yourself as invisible as is practical in the circumstances: according to your operational needs this might mean wearing a ‘ghilly suit’, named after a person who creeps up on deer for a living in Scotland, or just making sure you have no bright or shiny articles of equipment showing.

A US Navy SEAL sniper illustrating his skill at concealing himself although the use of black gloves makes this a less than perfect example of camouflage. (US Navy SEALs and SWCC)

Hopefully you have been trained in the basics of field-craft and camouflage as it may relate to your area of operation. What I shall do here is cover some of the basics in case you weren’t listening to the instructor or have forgotten. Then I will try to give you a few tips that might just give you an ‘edge’ – enough of an advantage to keep you on the winning – or at least surviving – side.

Lying in undergrowth, a camouflaged British infantry soldier looking down the telescopic sight of the new British-made Long Range L115A3 sniper rifle on Salisbury Plain, Warminster, England. Black boots and black sights stand out well don’t they? (Corbis)

When I was a young lad of 13, some 40 years ago, I was taught in the Army Cadets that concealment meant giving due consideration to: Shape, Shine, Shadow, Silhouette and Spacing. This has been slightly improved over the years with a new mnemonic – if you can remember them all: