MORTARS

A mortar is essentially a light, simple artillery piece which is restricted to the indirect fire role. That means you lob a bomb up into the air to drop onto the target rather than being able to shoot flat over open sights at the target. Despite this limitation the mortar can be devastatingly effective when used properly at the right time against the right target. Or it can be a waste of time and effort when used incorrectly.

Goal: When is the right time to employ this weapon? What can it do?

The best time to use mortars is against targets which are out in the open – perhaps troops on patrol or a vehicle convoy. In this case a concentrated barrage by a number of heavy mortars can do terrific execution. Where mortars come into their own is when a battery of three or more are carried on trucks or armoured personnel carriers (APCs). This means weight is less of a consideration so lots of ammunition can be carried. This kind of concentrated assault can have a very depressing effect on the enemy.

The standard procedure is as follows: mortar crews set up their emplacement – dug in safely – and use various techniques to aim at targets they usually cannot see. Ranging methods include surveying techniques and Global Positioning equipment. Suffice it to say that when they are given a target by grid reference they can drop a great many bombs onto it in just a few seconds.

A US Marine trains on an 81mm mortar. (USMC)

Some miles from the mortar battery a forward observation officer spots a group of enemy. He works out the exact position of the enemy and tells the mortar battery where they are. (Just coming into service is some clever kit with a point and shoot laser that sends the information directly to the mortars so you may have the benefit of using this). A short while later a concentrated rain of bombs comes down on the enemy with extreme prejudice. In the ideal situation they have no chance to hide because the mortar bombs come from behind a hill or landscape feature that hid the sound of their firing and so they are all destroyed in the open.

History: How did it develop to be the way it is?

Mortar tubes – the firing barrel – are pretty simple creatures and have been in use for as long as there has been artillery. What has changed over the years is simply that the tube has got lighter, the bombs more effective and the aiming gear more accurate. Mortars come in many sizes and are usually designated by their bore diameter or calibre. The smallest are the 2in/50mm and the 60mm with the next sizes up being the 81mm and the 82mm. The British and Canadians brought out the L16 81mm mortar and the US produced another 81mm called the M252 and both have been very successful. These strip down into three packs of 25lb/11kg each: base-plate, bipod and sites and tube.

The Chinese and Russians have both produced a 82mm mortar which had similar useful range and firepower as the first models used during World War II, used during the battles for Kursk, Stalingrad and Moscow. The 81mm cannot, of course, fire any captured 82mm ammunition but the Chinese 82mm variant can fire any captured 81mm ammunition. Damn clever those Chinese.

Operation: How does it work?

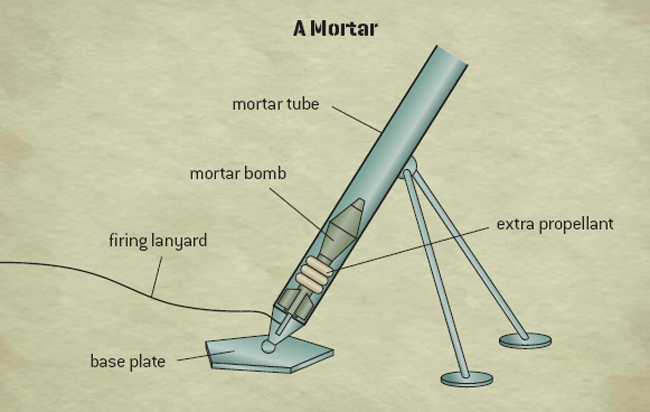

A mortar is a tube which is fired at an angle steeper than around 45° from vertical. In use a finned ‘bomb’ is dropped into the muzzle. The bomb has propellant charges in varied amounts placed around the stem of the fins so as to achieve different ranges combined with the angle of fire. When the bomb either hits a firing pin at the bottom of the tube, or the pin is projected by means of a trigger, the propellant charges are ignited forcing the bomb out of the mouth of the tube in the same way as a shell comes out of a cannon but at a steeper angle and lower velocity.

The advantages of mortars include relatively low weight for transportation – certainly a tiny fraction of an equivalent artillery piece – and a high rate of fire, often as fast as bombs can be dropped down the tube, which is much faster than artillery of a similar calibre.

A diagram of a typical mortar as used by armed forces around the world. The extra propellant looks like a tea bag.

Disadvantages include a lesser range than artillery – though still some miles with larger mortars – and that they can only fire in what is called the ‘indirect’ fashion. This means that where a cannon – say a tank main gun – can either shoot straight at the target like a rifle or up in the air and down onto the target like a Howitzer cannon, a mortar must always shoot up into the air and drop the bomb onto the target. Indirect fire has a greater range for the same muzzle velocity and can lob a heavy shell or bomb further but the approach is slow and can often warn the enemy. Soldiers soon learn to recognize and discriminate between the sounds of different mortars being fired and also come to know how long they have to get under cover. Firing from a distance a mortar bomb can travel for many seconds. Plenty of time to find a trench or break-up a packed formation.

Bomb damage: When a mortar shell comes down it explodes as it hits the ground – ground burst – and the burst together with the shrapnel goes up and out. If you are laid flat only a few yards from a mortar you will survive as the blast will go over you. If you are standing you will die. To catch you in a trench the bomb will actually have to land in the trench with you. This is extremely unlikely as the diagram in the artillery section shows.

If mortars might be used against you make sure you don’t dig trenches under, or spend any time under, trees. The reason being that the mortar bombs explode when they hit the branches of the trees above you and the blast comes down directly onto you so even a trench is not safe unless it has a solid roof. When terrorists use mortars they tend to use them in a primitive fashion without the accurate aiming or the massed fire of a battery. In my experience they will fire off a round or two at a building or patrol and then disappear. The effect is more a nuisance than anything else so don’t lose your head when you experience this for the first time.

In one country I was deployed to in Africa we used to be attacked every night at exactly 18:30 when it became dark so quickly it was like someone had flicked the light off. The opposition used to regularly turn up just before dark and get just close enough to sight our camp then let off a few rounds at us and run off into the night knowing we couldn’t follow them. We became very slack about this over time and everyone used to go to their slit trenches just five minutes early and have a smoke while the bombs came in. There were never any casualties despite scores of rounds – except once when I was cooking a fillet of gazelle over a fire suspended on a steel trip flare stake when I lost track of time. I got to my hole but the fillet was hit. There are no prizes for making life difficult in combat.

Skill: How do you use the weapon to maximum efficiency?

The light mortars of 60mm sometimes issued to infantry are a waste of time as they are heavy to carry and have no useful effect owing to inaccuracy, lack of punch, lack of range and the inability to carry sufficient ammunition. The 81mm mortar used by Western forces and the 82mm used by Russian, Chinese and insurgents are much more useful with a range of 5.5km and a rate of fire of 12–20 rounds per minute per tube. The 120mm used by various nations are quite excellent weapons with a range over 7km and a killing radius of 70m from each bomb burst. As I said earlier, the odd shell is just a nuisance as the enemy can hear it coming but if you pick your time and catch a convoy or infantry formation out in the open you can destroy them. This is particularly useful if you are being attacked by large numbers of the enemy across open ground.