"During the spring and autumn bird-migration season, the lights that illuminate the tower are turned off on foggy nights so they won't confuse birds, causing them to fly into the building." I told her, "Ten thousand birds die every year from smashing into windows," because I'd accidentally found that fact when I was doing some research about the windows in the Twin Towers. "That's a lot of birds," Mr. Black said. "And a lot of windows," Ruth said. I told them, "Yeah, so I invented a device that would detect when a bird is incredibly close to a building, and that would trigger an extremely loud birdcall from another skyscraper, and they'd be drawn to that. They'd bounce from one to another." "Like pinball," Mr. Black said. "What's pinball?" I asked. "But the birds would never leave Manhattan," Ruth said. "Which would be great," I told her, "because then your birdseed shirt would be reliable." "Would it be all right if I mentioned the ten thousand birds in my future tours?" I told her they didn't belong to me.

"A natural lightning rod, the Empire State Building is struck up to five hundred times each year. The outdoor observation deck is closed during thunderstorms, but the inside viewing areas remain open. Static electricity buildup is so mammoth on top of the building that, under the right conditions, if you stick your hand through the observatory fence, St. Elmo's fire will stream from your fingertips." "St. Elmo's fire is sooo awesome!" "Lovers who kiss up here may find their lips crackling with electric sparks." Mr. Black said, "That's my favorite part." She said, "Mine, too." I said, "Mine's the St. Elmo's fire." "The Empire State Building is located at latitude 40 degrees, 44 minutes, 53.977 seconds north; longitude 73 degrees, 59 minutes, 10.812 seconds west. Thank you."

"That was delightful," Mr. Black said. "Thank you," she said. I asked her how she knew all of that stuff. She said, "I know about this building because I love this building." That gave me heavy boots, because it reminded me of the lock that I still hadn't found, and how until I found it, I didn't love Dad enough. "What is it about this building?" Mr. Black asked. She said, "If I had an answer, it wouldn't really be love, would it?" "You're a terrific lady," he said, and then he asked where her family was from. "I was born in Ireland. My family came when I was a young girl." "Your parents?" "My parents were Irish." "And your grandparents?" "Irish." "That's marvelous news," Mr. Black said. "Why?" she asked, which was a question I was also wondering. "Because my family has nothing to do with Ireland. We came over on the Mayflower." I said, "Cool." Ruth said, "I'm not sure I understand." Mr. Black said, "We're not related." "Why would we be related?" "Because we have the same last name." Inside I thought, But technically she never actually said her last name was Black. And even if it actually was Black, why wasn't she asking how he knew her last name? Mr. Black took off his beret and got down onto one of his knees, which took him a long time. "At the risk of being too forthright, I was hoping I might have the pleasure of your company one afternoon. I will be disappointed, but in no way offended, if you decline." She turned her face away. "I'm sorry," he said, "I shouldn't have." She said, "I stay up here."

Mr. Black said, "What the?" "I stay up here." "Always?" "Yes." "For how long?" "Oh. A long time. Years." Mr. Black said, "Jose!" I asked her how. "What do you mean how?" "Where do you sleep?" "On nice nights, I'll sleep out here. But when it gets chilly, which is most nights up this high, I have a bed in one of the storage rooms." "What do you eat?" "There are two snack bars up here. And sometimes one of the young men will bring me food, if I have a taste for something different. As you know, New York offers so many different eating experiences."

I asked if they knew she was up there. "Who's they?" "I don't know, the people who own the building or whatever." "The building has been owned by a number of different people since I moved up here." "What about the workers?" "The workers come and go. The new ones see I'm here and assume I'm supposed to be here." "No one has told you to leave?" "Never."

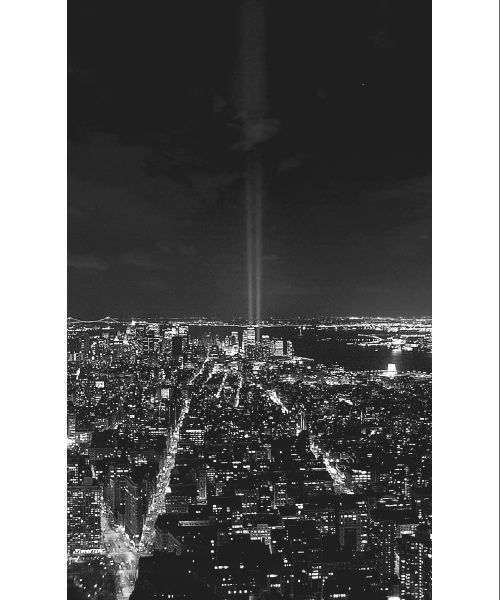

"Why don't you go down?" Mr. Black asked. She said, "I'm more comfortable here." "How could you be more comfortable here?" "It's hard to explain." "How did it start?" "My husband was a door-to-door salesman." "And?" "This was in the old days. He was always selling something or other. He loved the next thing that would change life. And he was always coming up with wonderful, crazy ideas. A bit like you," she said to me, which gave me heavy boots, because why couldn't I remind people of me? "One day he found a spotlight in an army surplus store. This was right after the war and you could find just about anything. He hooked it up to a car battery and fixed all of that to the crate he rolled around. He told me to go up to the observation deck of the Empire State Building, and as he walked around New York, he'd occasionally shine the light up at me so I could see where he was."

"It worked?" "Not during the day it didn't. It had to get quite dark before I could see the light, but once I could, it was amazing. It was as if all of the lights in New York were turned off except for his. That was how clearly I could see it." I asked her if she was exaggerating. She said, "I'm understating." Mr. Black said, "Maybe you're telling it exactly as it was."

"I remember that first night. I came up here and everyone was looking all over, pointing at the things to see. There are so many spectacular things to see. But only I had something pointing back at me." "Some one," I said. "Yes, something that was someone. I felt like a queen. Isn't that funny? Isn't it silly?" I shook my head no. She said, "I felt just like a queen. When the light went off, I knew his day was over, and I'd go down and meet him at home. When he died, I came back up here. It's silly." "No," I said. "It isn't." "I wasn't looking for him. I'm not a girl. But it gave me the same feeling that I'd had when it was daytime and I was looking for his light. I knew it was there, I just couldn't see it." Mr. Black took a step toward her.

"I couldn't bear to go home," she said. I asked why not, even though I was afraid I was going to learn something I didn't want to know. She said, "Because I knew he wouldn't be there." Mr. Black told her thank you, but she wasn't done. "I curled up in a corner that night, that corner over there, and fell asleep. Maybe I wanted the guards to notice me. I don't know. When I woke up in the middle of the night, I

was all alone. It was cold. I was scared. I walked to the railing. Right there. I'd never felt more alone. It was as if the building had become much taller. Or the city had become much darker. But I'd never felt more alive, either. I'd never felt more alive or alone."

"I wouldn't make you go down," Mr. Black said. "We could spend the afternoon up here." "I'm awkward," she said. "So am I," Mr. Black said. "I'm not very good company. I just told you everything I know." "I'm terrible company," Mr. Black said, although that wasn't true. "Ask him," he said, pointing at me. "It's true," I said, "he sucks." "You can tell me about this building all afternoon. That would be marvelous. That's how I want to spend my time." "I don't even have any lipstick." "Neither do I." She let out a laugh, and then she put her hand over her mouth, like she was angry at herself for forgetting her sadness.