I sat there while he made all the kids crack up. Even Mrs. Rigley cracked up, and so did her husband, who played the piano during the set changes. I didn't mention that she was my grandma, and I didn't tell him to stop. Outside, I was cracking up too. Inside, I was wishing that she were tucked away in a portable pocket, or that she'd also had an invisibility suit. I wished the two of us could go somewhere far away, like the Sixth Borough.

She was there again that night, in the back row, although only the first three rows were taken. I watched her from under the skull. She had her hand pressed against her ultraviolet heart, and I could hear her saying, "That's sad. That's so sad." I thought about the unfinished scarf, and the rock she carried across Broadway, and how she had lived so much life but still needed imaginary friends, and the one thousand thumb wars.

MARGIE CARSON. Hey, Hamlet, where's Polonius?

JIMMY SNYDER. At supper.

MARGIE CARSON. At supper! Where?

JIMMY SNYDER. Not where he eats, but where he's eaten.

MARGIE CARSON. Wow!

JIMMY SNYDER. A king can end up going through the guts of a beggar.

I felt, that night, on that stage, under that skull, incredibly close to everything in the universe, but also extremely alone. I wondered, for the first time in my life, if life was worth all the work it took to live. What exactly made it worth it? What's so horrible about being dead forever, and not feeling anything, and not even dreaming? What's so great about feeling and dreaming?

Jimmy put his hand under my face. "This is where his lips were that I used to kiss a lot. Where are your jokes now, your games, your songs?"

Maybe it was because of everything that had happened in those twelve weeks. Or maybe it was because I felt so close and alone that night. I just couldn't be dead any longer.

ME. Alas, poor Hamlet [I take JIMMY SNYDER's face into my hand]; I knew him, Horatio.

JIMMY SNYDER. But Yorick ... you're only ... a skull.

ME. So what? I don't care. Screw you.

JIMMY SNYDER. [whispers] This is not in the play. [He looks for help from MRS. RIGLEY, who is in the front row, flipping through the script. She draws circles in the air with her right hand, which is the universal sign for "improvise."]

ME. I knew him, Horatio; a jerk of infinite stupidity, a most excellent masturbator in the second-floor boys' bathroom—I have proof. Also, he's dyslexic.

JIMMY SNYDER. [Can't think of anything to say]

ME. Where be your gibes now, your gambols, your songs?

JIMMY SNYDER. What are you talking about?

ME. [Raises hand to scoreboard] Succotash my cocker spaniel, you fudging crevasse-hole dipshiitake!

JIMMY SNYDER. Huh?

ME. You are guilty of having abused those less strong than you: of making the lives of nerds like me and Toothpaste and The Minch almost impossible, of imitating mental retards, of prank-calling people who get almost no phone calls anyway, of terrorizing domesticated animals and old people—who, by the way, are smarter and more knowledgeable than you—of making fun of me just because I have a pussy ... And I've seen you litter, too.

JIMMY SNYDER. I never prank-called any retards.

ME. You were adopted.

JIMMY SNYDER. [Searches audience for his parents]

ME. And nobody loves you.

JIMMY SNYDER. [His eyes fill with tears]

ME. And you have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

JIMMY SNYDER. Huh?

ME. On behalf of the dead...[I pull the skull off my head. Even though it's made of papier-mache it's really hard. I smash it against JIMMY SNYDER's head, and I smash it again. He falls to the ground, because he is unconscious, and I can't believe how strong I actually am. I smash his head again with all my force and blood starts to come out of his nose and ears. But I still don't feel any sympathy for him. I want him to bleed, because he deserves it. And nothing else makes any sense. DAD doesn't make sense. MOM doesn't make sense. THE AUDIENCE doesn't make sense. The folding chairs and fog-machine fog don't make sense. Shakespeare doesn't make sense. The stars that I know are on the other side of the gym ceiling don't make sense. The only thing that makes any sense right then is my smashing JIMMY SNYDER 's face. His blood. I knock a bunch of his teeth into his mouth, and I think they go down his throat. There is blood everywhere, covering everything. I keep smashing the skull against his skull, which is also RON's skull (for letting MOM get on with life) and MOM's skull (for getting on with life) and DAD's skull (for dying) and GRANDMA's skull (for embarrassing me so much) and DR. FEIN's skull (for asking if any good could come out of DAD's death) and the skulls of everyone else I know. THE AUDIENCE is applauding, all of them, because I am making so much sense. They are giving me a standing ovation as I hit him again and again. I hear them call]

THE AUDIENCE. Thank you! Thank you, Oskar! We love you so much! We'll protect you!

It would have been great.

I looked out across the audience from underneath the skull, with Jimmy's hand under my chin. "Alas, poor Yorick." I saw Abe Black, and he saw me. I knew that we were sharing something with our eyes, but I didn't know what, and I didn't know if it mattered.

It was twelve weekends earlier that I'd gone to visit Abe Black in Coney Island. I'm very idealistic, but I knew I couldn't walk that far, so I took a cab. Even before we were out of Manhattan, I realized that the $7.68 in my wallet wasn't going to be enough. I don't know if you'd count it as a lie or not that I didn't say anything. It's just that I knew I had to get there, and there was no alternative. When the cab driver pulled over in front of the building, the meter said $76.50. I said, "Mr. Mahaltra, are you an optimist or a pessimist?" He said, "What?" I said, "Because unfortunately I only have seven dollars and sixty-eight cents." "Seven dollars?" "And sixty-eight cents." "This is not happening." "Unfortunately, it is. But if you give me your address, I promise I'll send you the rest." He put his head down on the steering wheel. I asked if he was OK. He said, "Keep your seven dollars and sixty-eight cents." I said, "I promise I'll send you the money. I promise." He handed me his card, which was actually the card of a dentist, but he had written his address on the other side. Then he said something in some other language that wasn't French. "Are you mad at me?"

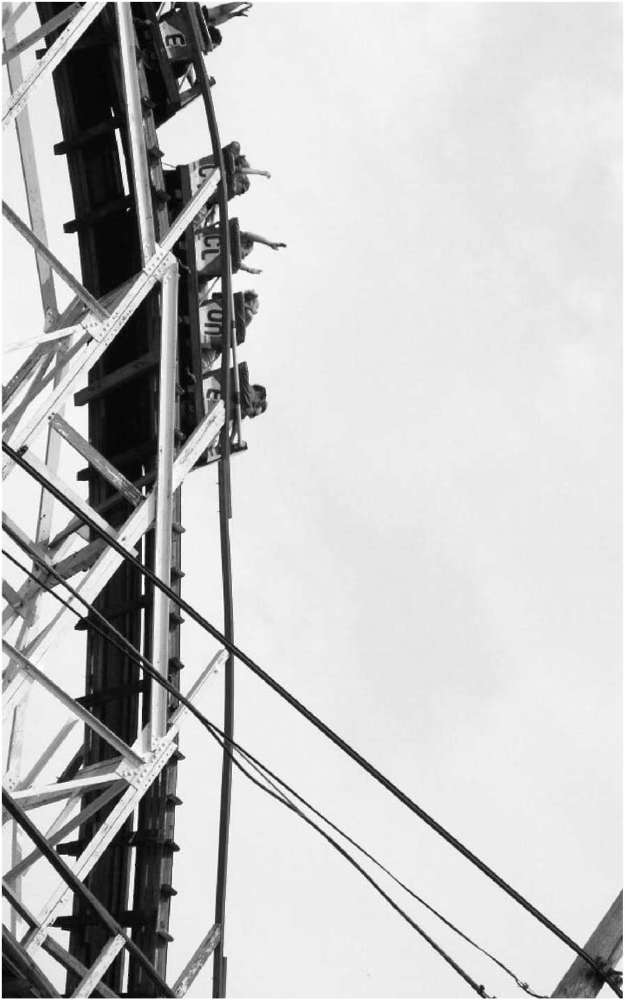

Obviously I'm incredibly panicky about roller coasters, but Abe convinced me to ride one with him. "It would be a shame to die without riding the Cyclone," he told me. "It would be a shame to die," I told him. "Yeah," he said, "but with the Cyclone you can choose." We sat in the front car, and Abe lifted his hands in the air on the downhill parts. I kept wondering if what I was feeling was at all like falling.

In my head, I tried to calculate all of the forces that kept the car on the tracks and me in the car. There was gravity, obviously. And centrifugal force. And momentum. And the friction between the wheels and the tracks. And wind resistance, I think, or something. Dad used to teach me physics with crayons on paper tablecloths while we waited for our pancakes. He would have been able to explain everything.

The ocean smelled weird, and so did the food they were selling on

the boardwalk, like funnel cakes and cotton candy and hot dogs. It was an almost perfect day, except that Abe didn't know anything about the key or about Dad. He said he was driving into Manhattan and could give me a ride if I wanted one. I told him, "I don't get in cars with strangers, and how did you know I was going to Manhattan?" He said, "We're not strangers, and I don't know how I knew." "Do you have an SUV?" "No." "Good. Do you have a gas-electric hybrid car?" "No." "Bad."