I passed beneath the portico of a stone-columned building, the largest of the ten or so in the vicinity, and walked up the steps. A great clock surmounted the roof, surrounded by scaffolding, its black hands stuck suspiciously on 4:20.

Inside, the building was dim and stale. The floor was constructed of burnished marble, and the walls of the foyer, wooden and intricately carved, were adorned with large portraits of former deans, founders, and dead professors. A life-size statue stood in the center of the circular room, staring vacuously at me. I didn’t stop to see who he was.

Glass double doors led into the office of the university registrar. I caught my reflection as I pushed them open—my hair and recent beard now brown, a pair of wire-framed spectacles on the bridge of my nose. In jeans and wearing a faded denim shirt under my jacket, I looked nothing like myself.

In the bright windowless room, there were several open cubicles, each holding a desk and portioned off from the cubicle next to it. I walked to the closest one, where a woman typed fervidly on a computer. She looked up from the screen and smiled as I approached.

“May I help you?” she asked. I sat down in the chair before her desk. The constant pecking of fingers on keyboards would’ve driven me insane.

“I need a campus map, a class directory for this semester, and a campus phone book.”

She opened a filing cabinet and withdrew a booklet and a blue pamphlet.

“Here’s a map and here’s the phone book,” she said, setting the items on her tidy desk. “I’ll have to get a class directory from the closet.” She walked across the room, mumbling something to another secretary as she passed. I opened the phone book. It was only fifty pages thick, with the faculty listings in the first ten pages and those of the two thousand students in the remaining forty. I thumbed through it to the P’s.

I skipped over the entries for Page and Paine, then spotted “Parker, David L.” The information given beneath the name was sparse—only an office number—Gerard 209—and a corresponding phone number.

The woman returned and handed me a directory of classes. “Here you are, sir.”

“Thanks. Are the students in class today?” I asked, rising.

She shook her head doubtfully. “They’re supposed to be,” she said, “but this is the first cold snap of the season, so a fair number probably played hooky to go skiing.”

I thanked her again, then walked out of the office and into the foyer, where I passed three college girls standing in a circle beside the statue, whispering to each other. Exiting the building, I walked through snow flurries to the gazebo and sat down on the bench that circumnavigated the interior of the structure. First, I unfolded the map and located Gerard Hall. I could see it from where I sat, a two-story building that displayed the same charmingly decrepit brick as the others.

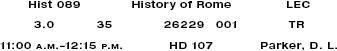

With hot breath, I warmed my hands, then opened the directory of classes, a thick booklet, its first ten pages crammed with mountains of information regarding registering for classes and buying books. I found an alphabetical listing of the classes and their schedules, and flipping through anthropology, biology, communications, English, and French, stopped finally at the roster of history classes for fall ’96. There was a full page of history courses, and I skimmed down the list until I saw his name:

It appeared to be the only course he taught, and, glancing at my watch, I realized that it was currently in session.

According to the building abbreviation key, HD stood for Howard Hall. I found it on the blue map. Just twenty yards away, it was one of the closest buildings to the gazebo. An apprehensive knocking started in my chest as I looked down the walkway leading to its entrance.

Before I could dissuade myself, I was walking down the steps, away from the gazebo, heading toward Howard Hall. To the left of the registrar’s building, it made up the eastern wall of the quasi courtyard surrounding the gazebo. Two students smoked on the steps, and I passed them and touched the door, thinking, What if this isn’t him? Then I’ll go to prison, and Walter and his family will die.

As the door closed behind me, I heard his voice. It haunted the first floor of Howard Hall, its soft-spoken intensity reeling me back to the Wyoming desert. I walked slowly on, leaving the foyer, where political notices, ads for roommates, and a host of other flyers papered the walls. In the darker hall, light spilled from one door. I heard a collection of voices, then an outburst of laughter. Orson’s voice rose above the rumblings of his students, and I turned right and walked down the hallway, taking care my steps didn’t echo off the floor.

His voice grew louder, and I could soon understand every word. Stopping several feet from the doorway, I leaned against the wall. From the volume of laughter, I approximated the class size at thirty or forty students. Orson spoke again, his voice directly across from me on the other side of the wall. Though I wanted to run, to hide in a closet or a bathroom stall far from that voice, I remained to listen, trusting he’d have no reason to step into the hall.

“I want you to put your pens and pencils down,” he said, and the sound of writing implements falling onto wood engulfed the room. “To understand history, you have to see it. It’s more than words on a page. It happened. You can’t ever forget that. Put your head on your desk,” he said. “Everybody. Go on. Now close your eyes.” His footsteps approached the door. He flipped a switch, the room went black, and the footsteps trailed away.

“Megalomania,” he said. “Somebody tell me what it means.”

A male voice sounded in the dark. “Delusions of omnipotence.”

“Good,” Orson said. “It’s a mental disorder, so keep that in mind, too.”

The professor kept silent for half a minute, and the room was still. When he spoke again, his voice had a controlled, musical resonance.

“The year is a.d. thirty-nine,” he began. “You’re a Roman senator, and you and your wife have been invited to watch the gladiatorial games with the young emperor, Gaius Caligula.

“During the lunch interlude, as humiliores are executed ad bestias before a rejoicing crowd, Caligula stands up, takes your wife by the hand, and leaves with her, escorted by his guards.

“You know exactly what’s happening, and it’s apparent to the other senators, because the same thing has happened to their wives. But you do nothing. You just sit on the stone steps, under the blue, spring sky, watching the lions chase their prey.

“An hour later, Gaius returns with your wife. When she sits down beside you, you notice a purple bruise on her face. She’s rattled, her clothes are torn, and she refuses to look at you. There are six other senators who’ve been invited along with you, and suddenly you hear Caligula speak to them.

“‘Her breasts are quite small,’ he says, loudly enough for everyone around to hear. ‘She’s a sexual bore. I’d rather watch the lions feed than fuck her …again.’

“He laughs and pats you on the back, and everyone laughs with him. No one contradicts Gaius. No one challenges the emperor. It’s pure sycophancy, and you sit there, boiling, wishing you’d never come. But to speak one word against Caligula would be your family’s certain death. It’s best just to keep silent and pray you never receive another invitation.”

Orson’s footsteps approached the doorway. I stepped back, but he’d only come for the lights. The room filled with the sound of students shifting in their seats and reopening notebooks.

“Next Tuesday,” he said, “we’ll talk about Caligula. I notice some of your classmates aren’t with us today, and that may or may not have something to do with the snowstorm in the mountains last night.” The class laughed. It was obvious by now that his students adored him.