“No,” she said, firmly. “Never. And for your information, Savannah wasn’t a ‘cooker’ either.”

The woman in the vest shrugged a little and backed off. “I’m telling you what I know. Why are you here, then?”

“We wanted to ask her something . . .” Taylor said, trying not to betray any emotion as she scanned the blackened space beyond the picker.

Hayley added to her sister’s story. “About the pheasants. My sister and I were going to raise them this year. Savannah was going to help us.”

“If you knew her so well, why didn’t you know about the fire? It was on the news. Twice, I think,” the picker said.

They ignored her and moved toward where the front door had once stood. They thought about the night they’d come to this very spot with Shania and Colton. How they had seen the tape that threatened to expose their gift. How Savannah had seemed genuinely concerned about them. Her letter was proof of that. And now she was dead under suspicious circumstances. Though they didn’t know Savannah Osteen well, both girls felt grief seize them. They didn’t cry. They simply stood silently mourning her death.

And maybe, just a little, mourning the opportunity to find out more about themselves.

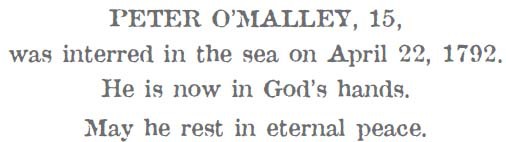

The picker moved on, and the girls got into the car. Hayley put it in gear and drove back to the main road. Taylor kept her eyes on the scorched earth that had been Savannah’s home and had become her grave. As the property receded from Taylor’s view, her mind wandered to another grave—a much, much older one—in the Port Gamble Cemetery. It was marked with a small, faded plaque:

According to the legend, passed down from generation to generation in Port Gamble, young Peter had died from cholera and his wasted body had been buried in what was later named Port Gamble Bay inside a salt-cod-crate coffin. The coffin had washed up on shore, and was forced open by three curious S’Klallam Indian boys, who found nothing inside except a silver crucifix, a swarm of flies, and a horrible odor of death. Soon after, the story went, the oyster beds died and the seabirds refused to nest there. People were certain the site was cursed. They called the place Memalucet, which means “empty box.” Those with darker minds called it Empty Coffin. Decades later, Port Gamble was founded there.

If only Port Gamble had fewer full coffins, Taylor thought darkly, and more empty ones.

Hayley’s voice brought Taylor back to the present. “Someone killed Savannah because of us,” Hayley said, her eyes fastened to the rearview mirror.

“Yeah,” Taylor said in the softest voice. “I know. I don’t care how weirded out Mom is about us and the crash. She knows about our connection. She saw our message to Savannah before Savannah’s sister died,” Taylor said. “We have to get her to talk to us. We’re her daughters. She owes it to us.”

Hayley understood her sister’s feelings completely. Yet, she also felt sorry for her mother. There must be a reason she didn’t want to talk about any of it. The reason had to be big.

IT WASN’T EVERY NIGHT, but several times a week Valerie Ryan somehow managed to serve dinner at the table, with the entire family at the same time. Sometimes she served take-out, and occasionally dinner was something she’d tossed together in the Crock-Pot before heading off to work at the hospital. Kevin cooked, too, but his idea of a meal was meat of some kind. No side dishes. No vegetable option.

It was pizza that night—vegetarian “with meat” and a Caesar salad. Taylor’s would be served without croutons, which she called “dead bread.”

“How was your day?” Valerie asked no one in particular. It was just a question tossed out into the open. Chicken scratch tossed in the yard.

Kevin answered. “Fair. Having a hard time with the apprehension scene. Tough to make it exciting for the reader when the killer just basically turns himself in.”

She nodded. “I see your point.” She turned toward the girls. “Hayley?”

“Mine sucked.”

Taylor jumped in. “Mine, too.”

Valerie stopped eating, her eyes full of concern. “Why, what happened?”

Taylor put down her fork and stayed riveted to her mother. “We found out that a friend of ours died.”

“Oh no,” Valerie said, looking at Kevin with concern, red flag up. “Was it another kid from school?”

Taylor shook her head. “No. I said a friend of ours. Yours, mine, Dad’s, Hayley’s. All of us.”

“Really? Who?” Valerie asked.

“Yeah, Taylor, who died?” Kevin repeated.

“Savannah,” she said, waiting for a reaction from her parents. None came.

“We don’t know anyone named Savannah,” Valerie said carefully, searching her daughters’ and husband’s eyes. She scooted to the edge of her seat, as if readying herself to make a hasty escape.

“Savannah Osteen,” Hayley said.

Valerie glanced at Kevin nervously.

“Isn’t that the name of the researcher from years ago, Val?” Kevin asked. “Wasn’t she the one who came out here when the girls were little?”

“I think so,” Valerie said, turning her eyes down to her suddenly very interesting plate.

Both girls felt sick to their stomachs. Their mother knew full well who Savannah Osteen was, and they knew it. The proof was only inches away. Yet there, at the dinner table, Valerie tried to play dumb.

“What happened to Savannah?” Kevin asked.

“Well, her house blew up and she died. Allegedly, she was manufacturing methamphetamine,” Hayley said.

“I remember her now, Kevin,” Valerie said tentatively and pushed her croutons underneath some greens. “Didn’t Savannah get fired from the university for using drugs or something along those lines?”

“Mom,” Hayley said, her voice getting louder and firmer, “Savannah didn’t get fired for that, and you know it. What’s wrong with you? Why don’t you just admit you know all about Savannah and me and Taylor?”

Valerie pushed back from the table and stood. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Hayley stood. “Really, Mom? You’re really going to be that way?” She reached under her place mat and pulled out Savannah’s letter.

“I’m talking about this, Mom! This letter!” She held it out, but Valerie didn’t take it. Instead, Valerie looked first at Kevin and then back at the girls. The room was still, tense, and filled with the hurt of a million lies.

Seeing that she was adrift without one bit of support, Valerie turned back to Hayley. She took the letter. “Don’t you ever speak to me like that again, Hayley. It is rude and disrespectful. And I don’t appreciate you going through my things either.”

Hayley loved her mother with every fiber of her being, but she didn’t think love meant burying family secrets—certainly not ones as big as this. “It’s rude and disrespectful, Mom, to lie to your kids.”

Taylor’s mouth fell open in disbelief.

Valerie shot Kevin a look that was a request for a lifeline, if ever there was one. “Kevin, are you going to let them talk to me like that?”

Kevin lasered his eyes on his wife, and then he turned to his daughters. “Girls,” he said as sternly as he could, “apologize to your mother.”

Taylor finally spoke up, though her voice squeaked in apprehension. “We have questions, Dad, and she won’t answer us.”

On that note, Valerie turned, her feet hitting the floorboards harder with each step away from the kitchen. Her bedroom door shut. It wasn’t a slam, but it was close. It meant: You’ve hurt me. You’ve made me angry. Do not ever push me where I don’t want to go.

“She won’t ever talk about it,” Hayley said, her eyes now back on her father’s.

Kevin’s thoughts wandered back to the strange e-mail he received from the newspaper reporter last year. It was about Savannah, and he and Val had fought when he brought it up. She hadn’t shared what happened then, and she clearly wasn’t going to now. Kevin picked up his plate. Dinner was over. “I don’t know exactly what this is all about. Maybe, honey, she can’t. Don’t you get that? Don’t you both understand that some things are just too painful to relive?”