Raymond opened the car door.

“Mr. Shaw?”

“What?”

“Shoot through the head. After first shot, walk close, place second shot.”

“I know. She told me.” He opened the door quickly, got out quickly, and slammed it shut. He crossed the street as the panel truck pulled away, the pistol held at his waist under his light raincoat, the rain striking his face.

He felt the sadness of Lucifer. He moved in the flat, relentless rhythm of the oboe passages in Bald Mountain. Colors of anguish moved behind his eyes in VanGoghian swirls, having lifted the edges to give an elevation to the despair. His nameless grief had handles, which he lifted, carrying himself forward toward the center of the pain.

The doors of the house, outer and inner, opened with the master keys. There were no lights in the rooms on the main floor, only the night light over the foot of the stairs. Raymond moved toward the staircase, the pistol hanging at his side, gripped in his left hand. As his foot touched the first riser he heard a sound in the back of the house. He froze where he was until he could identify it.

Senator Jordan appeared in pajamas, slippers, and robe. His silver hair was ruffled into a halo of duck feathers. He saw Raymond as he stood under the light leaning against the wall, but showed no surprise.

“Ah, Raymond. I didn’t hear you come in. Didn’t expect to see you until around breakfast time tomorrow morning. I got hungry. If I were only as hungry in a restaurant as I am after I’ve been asleep in a nice, warm bed for a few hours, I could be rounder and wider than the fat lady in the circus. Are you hungry, Raymond?”

“No, sir.”

“Let’s go upstairs. I’ll force some good whisky on you. Combat the rain. Soothe you after traveling and any number of other good reasons.” He swept past Raymond and went up the stairs ahead of him. Raymond followed, the pistol heavy in his hand.

“Jocie said you had to go down to see your mother and the Speaker.”

“Yes, sir.”

“How was the Speaker?”

“I—I didn’t see him, sir.”

“I hope you didn’t get yourself all upset over those charges of Iselin’s.”

“Sir, when I read that story on the plane going to Washington I decided what I should have decided long ago. I decided that I owed him a beating.”

“I hope you didn’t—”

“No, sir.”

“Matter of fact, an attack from John Iselin can help a good deal. I’ll show you some of the mail. Never got so much supporting mail in twenty-two years in the Senate.”

“I’m happy to hear it, sir.” They passed into the Senator’s bedroom.

“Bottle of whisky right on top of that desk,” the Senator said as he climbed into bed and pulled up the covers. “Help yourself. What the hell is that in your hand?”

Raymond lifted the pistol and stared at it as though he weren’t sure himself. “It’s a pistol, sir.”

The Senator stared, dumbfounded, at the pistol and at Raymond. “Is that a silencer?” he managed to say.

“Yes, sir.”

“Why are you carrying a pistol?”

Raymond seemed to try to answer, but he was unable to. He opened his mouth, closed it again. He opened it again, but he could not make himself talk. He was lifting the pistol slowly.

“Raymond! No!” the Senator shouted in a great voice. “What are you doing?”

The door on the far side of the room burst open. Jocie came into the room saying, “Daddy, what is it? What is it?” just as Raymond shot him. A hole appeared magically in the Senator’s forehead.

“Raymond! Raymond, darling! Raymond!” Jocie cried out in full scream. He ignored her. He crossed quickly to the Senator’s side and shot again, into the right ear. Jocie could not stop screaming. She came running across the room at him, her arms outstretched imploringly, her face punished with horror. He shot her without moving, from the left hand. The bullet went through her right eye at a range of seven feet. Head going backward in a punched snap, knees going forward, she fell at his feet. His second shot went directly downward, through her left eye.

He put out the bed light and fumbled his way to the stairs. He could not control his grief any longer but he could not understand why he wept. He could not see. Loss, loss, loss, loss, loss, loss, loss.

When he climbed to the mattress in the back of the panel truck the sounds he was making were so piteous that Chunjin, although expressionless, seemed to be deeply moved by them because he took the pistol from Raymond’s hand and struck him on the back of the head, bringing forgetfulness to save him.

The bodies were discovered in the morning by the Jordan housekeeper, Nora Lemmon. Radio and TV news shows had the story at eleven-eighteen, having interrupted all regular programs with the flash. In Washington, via consecutive telephone calls to the news agencies, Senator Iselin offered the explanation that the murders bore out his charges of treason against Jordan who had undoubtedly been murdered by Soviet agents to silence him forever. The Monday morning editions of all newspapers were on the streets of principal cities on Sunday afternoon, five hours before the normal bulldog edition hit the street.

Raymond’s mother did not awaken him when the FBI called to ask if she could assist them in establishing her son’s present whereabouts. Colonel Marco called from New York as Raymond’s closest friend, saying he feared that Raymond might have harmed himself in his grief over his wife’s tragic death, almost begging Mrs. Iselin to tell him where her son was so that he might comfort him. Raymond’s mother hit herself with a heavy fix late Sunday afternoon because she could not rid her mind of the picture of that lovely, lovely, lovely dead girl which looked out at her from every newspaper. She went into a deep sleep. Johnny called all the papers and news agencies and announced that his wife was prostrate over the loss of a dear and wonderful girl whom she had loved as a daughter. He told the papers that he would not attend the opening day of the convention “even if it costs me the White House” because of this terrible, terrible loss and their affliction of grief. Asked where his stepson was, the Senator replied that Raymond was “undoubtedly in retreat, praying to God for understanding to carry on somehow.”

Twenty-Five

SUNDAY NIGHT MARCO DRANK GIN WITH HIS head resting across Eugénie Rose’s ample lap and listened to the Zeitgeist of zither music until the gin had softened the rims of his memory. He looked straight up, right through the ceiling, his face an Aztec mask. Rose had not spoken because she had too much to ask him and he did not speak for a long time because he had too much to tell her. He pulled some sheets of white paper from the breast pocket of his jacket, which had been hung across the back of the chair beside them.

“I grabbed this from the files this afternoon,” he said. “It’s a verbatim report. Fella took it down on tape in the Argentine. Read it to me, hah?”

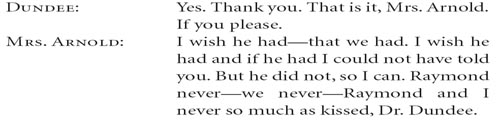

Rosie took the paper and read aloud. “What follows is a transcribed conversation between Mrs. Seward Arnold and Agent Graham Dundee as transcribed by Carmelita Barajas and witnessed by Dolores Freg on February 16, 1959.” Rosie looked for a moment as though she would ask a question, then seemed to think better of it. She continued to read from the paper while Marco stared from her lap at far away. She read slowly and softly.

Marco reached up and took the transcript gently out of Rosie’s hands. He folded it and slid it back into the pocket of his jacket.