We followed him inside. The shack was modest and tiny, a far cry from Miss Peregrine’s queenly setup. The entirety of its furniture was a small bed, a wardrobe, and a rolltop desk. A telescope sat mounted on a tripod, aimed out the window: Miss Wren’s lookout station, where she watched for trouble, and the comings and goings of her spy pigeons.

Addison went to the desk. “Should you have any difficulty locating the road,” he said, “there’s a map of the forest in here.”

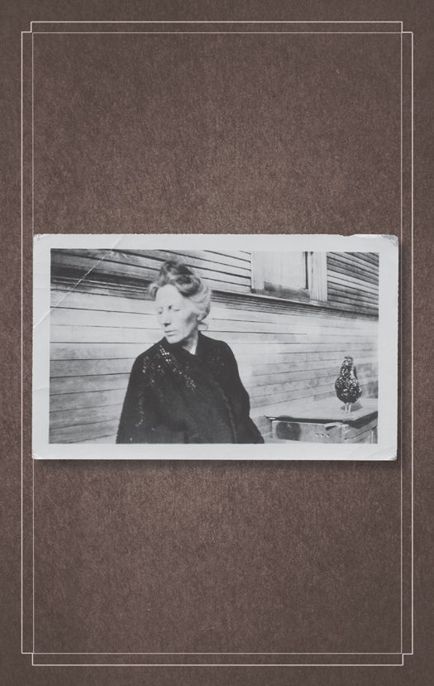

Emma opened the desk and found the map, an old, yellowed roll of paper. Underneath it was a creased snapshot. It showed a woman in a black sequined shawl with gray-streaked hair worn in a dramatic upsweep. She was standing next to a chicken. At first glance the photo looked like a discard, taken during an off moment when the woman was looking away with her eyes closed, and yet there was something just right about it, too—how the woman’s hair and clothes matched the black-and-white speckle of the chicken’s feathers; how she and the chicken were facing opposite directions, implying some odd connection between them, as if they were speaking without words; dreaming at one another.

This, clearly, was Miss Wren.

Addison saw the photo and seemed to wince. I could tell he was worried for her, much more than he wanted to admit. “Please don’t take this as an endorsement of your suicidal plans,” he said, “but if you should succeed in your mad quest … and should happen to encounter Miss Wren along the way … you might consider … I mean, might you consider …”

“We’ll send her home,” Emma said, and then scratched him on the head. It was a perfectly normal thing to do to a dog, but seemed a strange thing to do to a talking one.

“Dog bless you,” Addison replied.

Then I tried petting him, but he reared up on his hind legs and said, “Do you mind? Keep your hands at bay, sir!”

“Sorry,” I mumbled, and in the awkward moment that followed it became obvious that it was time to go.

We climbed down the tower to join our friends, where we exchanged tearful goodbyes with Claire and Fiona under the big shade tree. By now Claire had been given a cushion and blanket to lie on, and like a princess she received us one by one at her makeshift bedside on the ground, extracting promises as we knelt down beside her.

“Promise you’ll come back,” she said to me when it was my turn, “and promise you’ll save Miss Peregrine.”

“I’ll try my best,” I said.

“That isn’t good enough!” she said sternly.

“I’ll come back,” I said. “I promise.”

“And save Miss Peregrine!”

“And save Miss Peregrine,” I repeated, though the words felt empty; the more confident I tried to sound, the less confident I actually felt.

“Good,” she said with a nod. “It’s been awfully nice knowing you, Jacob, and I’m glad you came to stay.”

“Me, too,” I said, and then I got up quickly because her bright, blonde-framed face was so earnest it killed me. She believed, unequivocally, everything we told her: that she and Fiona would be all right here, among these strange animals, in a loop abandoned by its ymbryne. That we’d return for them. I hoped with all my heart that it was more than just theater, staged to make this hard thing we had to do seem possible.

Hugh and Fiona stood off to one side, their hands linked and foreheads touching, saying goodbye in their own quiet way. Finally, we’d all finished with Claire and were ready to go, but no one wanted to disturb them, so we stood watching as Fiona pulled away from Hugh, shook a few seeds from her nest of wild hair, and grew a rose bush heavy with red flowers right where they stood. Hugh’s bees rushed to pollinate it, and while they were occupied—as if she’d done it just so they could have a moment to themselves—Fiona embraced him and whispered something in his ear, and Hugh nodded and whispered something back. When they finally turned and saw all of us looking, Fiona blushed, and Hugh came toward us with his hands jammed in his pockets, his bees trailing behind him, and growled, “Let’s go, show’s over.”

We began our trek down the mountain just as dusk was falling. The animals accompanied us as far as the sheer rock wall.

Olive said to them, “Won’t you all come with us?”

The emu-raffe snorted. “We wouldn’t last five minutes out there! You can at least hope to pass for normal. But one look at me …” She wiggled her forearm-less body. “I’d be shot, stuffed, and mounted in no time.”

Then the dog approached Emma and said, “If I could ask one last thing of you …”

“You’ve been so kind,” she replied. “Anything.”

“Would you mind terribly lighting my pipe? We have no matches here; I haven’t had a real smoke in years.”

Emma obliged him, touching a lit finger to the bowl of his pipe. The dog took a long, satisfied puff and said, “Best of luck to you, peculiar children.”

We clung to the swinging net like a tribe of monkeys, bumping clumsily down the rock face while the pulley squealed and the rope creaked. Coming to earth in a knotted pile, we extricated ourselves from its tangles in what could’ve been a lost Three Stooges bit; several times I thought I was free, only to try standing and fall flat on my face again with a cartoonish whump! The dead hollow lay just feet away, its tentacles splayed like starfish arms from beneath the boulder that had crushed it. I almost felt embarrassed for it: that such a fearsome creature had let itself be laid low by the likes of us. Next time—if there was a next time—I didn’t think we’d be so lucky.

We tiptoed around the hollow’s reeking carcass. Charged down the mountain as fast as we could, given the limits of the treacherous path and Bronwyn’s volatile cargo. Once we’d reached flat land we were able to follow our own tracks back through the squishy moss of the forest floor. We found the lake again just as the sun was setting and bats were screeching out of their hidden roosts. They seemed to bear some unintelligible warning from the world of night, crying and circling overhead as we splashed through the shallows toward the stone giant. We climbed up to his mouth and pitched ourselves down his throat, then swam out the back of him into the instantly cooler water and brighter light of midday, September 1940.

The others surfaced around me, squealing and holding their ears, everyone feeling the pressure that accompanied quick temporal shifts.

“It’s like an airplane taking off,” I said, working my jaw to release the air.

“Never flown in an airplane,” said Horace, brushing water from the brim of his hat.

“Or when you’re on the highway and someone rolls down a window,” I said.

“What’s a highway?” asked Olive.

“Forget it.”

Emma shushed us. “Listen!”

In the distance I could hear dogs barking. They seemed far away, but sound traveled strangely in deep woods, and distances could be deceiving. “We’ll have to move quickly,” Emma said. “Until I say different, no one make a sound—and that includes you, headmistress!”

“I’ll throw an exploding egg at the first dog that gets near us,” said Hugh. “That’ll teach them to chase peculiars.”

“Don’t you dare,” said Bronwyn. “Mishandle one egg and you’re liable to set them all off!”

We waded out of the lake and started back through the forest, Millard navigating with Miss Wren’s creased map. After half an hour we came to the dirt road Addison had pointed to from the top of the tower. We stood in the ruts of an old wagon track while Millard studied the map, turning it sideways, squinting at its microscopic markings. I reached into the pocket of my jeans for my phone, thinking I’d call up a map of my own—an old habit—then found myself tapping on a blank rectangle of glass that refused to light up. It was dead, of course: wet, chargeless, and fifty years from the nearest cell tower. My phone was the only thing I owned that had survived our disaster at sea, but it was useless here, an alien object. I tossed it into the woods. Thirty seconds later I felt a pang of regret and ran to retrieve it. For reasons that weren’t entirely clear to me, I wasn’t quite ready to let it go.